These women in translation hail from every corner of the globe, from Sweden to Argentina to Japan via the Middle East and Central Europe. They have grown up, and written literature about, countries where women are not given equal opportunities. They are feminists, powerful people, genius writers and world-builders. And here are some of the best modern novels by women in translation.

The Best Modern Books by Women in Translation

This is a handful of fantastic modern books by fantastic women in translation. If you want to enjoy Women in Translation Month while still staying up-to-date with the best of women in translation, allow us to assist you with this list of incredible women authors.

Read More: 9 Transgender Stories by Trans Writers

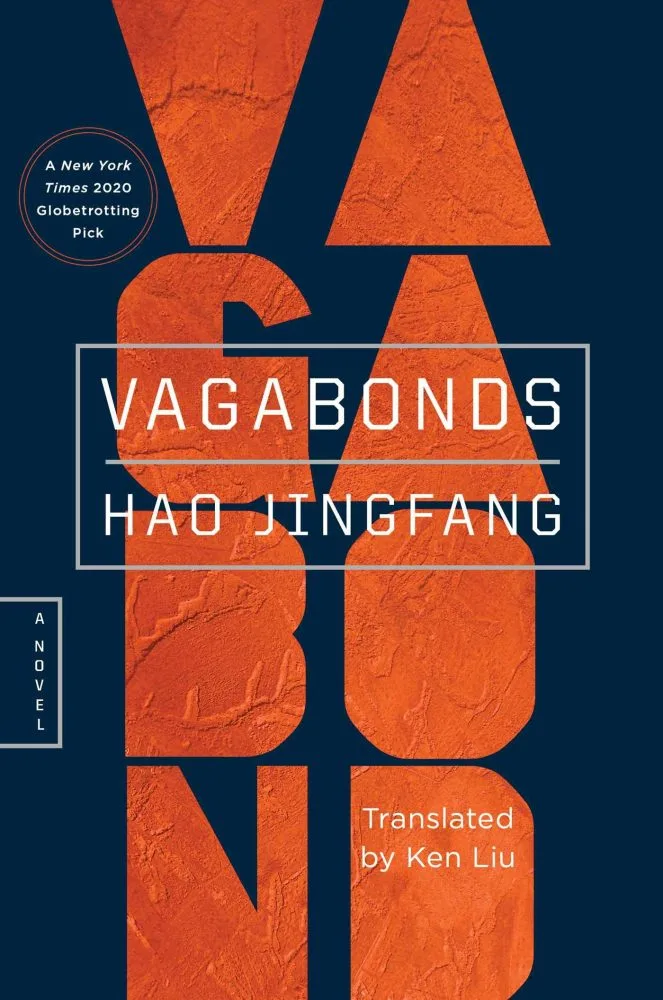

Vagabonds by Hao Jingfang

Translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu

Vagabonds is a Chinese sci-fi novel set in a future some three hundred years from now, as Mars has been colonised and humanity is now two groups: Terrans and Martians. After its colonisation, Mars was dependent on Earth for supplies, but eventually wanted to strike out on its own and a war of independence ensued. After the war, Earth resembles the greatest extremes of capitalism and Mars is something of a communist utopia.

Forty years after the war, our protagonist, Luoying, is a young Martian woman who has returned to Mars after years of living and studying on Earth as part of the Mercury Group (a batch of young people sent over to learn and improve interplanetary relations).

Mars resembles a communist utopia while Earth has grown in its capitalistic power. After spending time Earth, Luoying now finds herself torn between the two planets — a vagabond without a true home. This Chinese sci-fi novel explores, with a mature philosophical edge, these two opposed ideologies and what happens when they’re left to flourish unimpeded.

It’s a political saga first and foremost, set against an exciting future sci-fi backdrop.

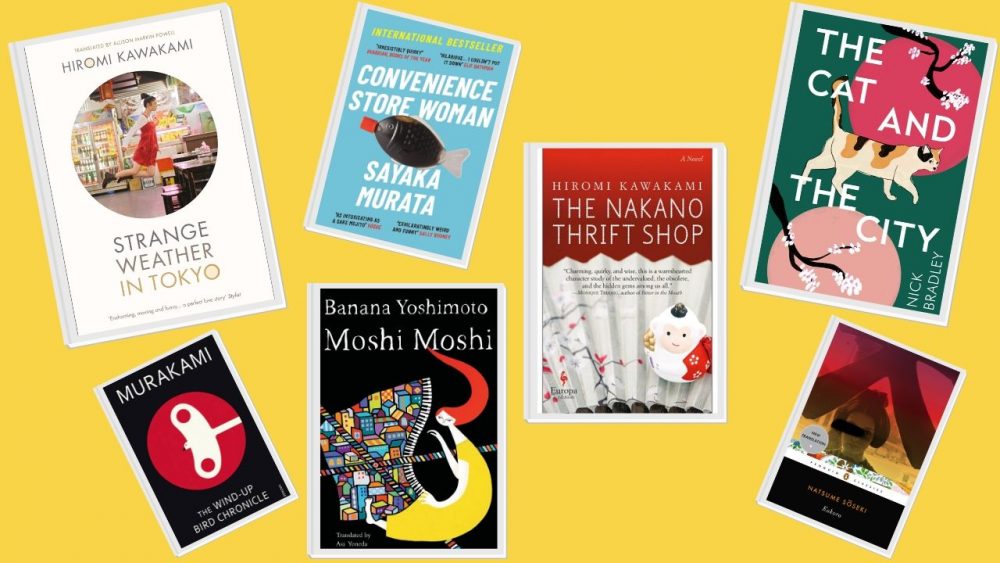

There’s No Such Thing As An Easy Job by Kikuko Tsumura

Translated from the Japanese by Polly Barton

A novel of 400 pages and five chunky chapters, a novel which follows a woman damaged by burnout and afraid of challenges, should not be half as engaging and funny as this one. But in There’s No Such Thing As An Easy Job, Kikuko Tsumura and Polly Barton settle us comfortably into the life of this witty, sweet, tenacious, and deeply charming woman.

We spend the novel closely bound to her, sharing in her frustrations and dismay, enjoying her infectious sense of hope and the gambles she takes. This book, by one of Japan’s coolest women in translation, reflects that infuriating feeling of smacking one’s head against a brick wall; a feeling we all know too well.

It offers a quiet mirror up to late-stage capitalism and Japanese work culture, but it’s actually far more concerned with looking at how each job offers its workers a chance to make change, to affect the world and to have fun (even if we have to make our own).

There’s No Such Thing As An Easy Job is a sweet and charming book that celebrates work culture as much as it condemns it. And it shows us that, while work is often a thing we fight against, there are more ways to win that fight than we might think.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Theatre of War by Andrea Jeftanovic

Translated from the Spanish by Frances Riddle

Theatre of War, the first Chilean novel to be published in translation from Charco Press, is setting a high bar going forward. This is my favourite book to be published by Charco Press in 2020 and a wonderful way to ring out the year for this outstanding indie press.

This is a scrawny novel by one of Chile’s most inspiring and powerful women in translation that blends intimate journaling with playful theatrical presentation to deliver an emotionally exhausting journey. It laments the lives of its characters in the aftermath of war.

It shows us that wars last far longer than battles in the hearts, minds, the very DNA of those who have to suffer them. Theatre of War is an absolute triumph or literature.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli

Translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette

Separated into two interconnected fifty-page stories, Minor Detail is a short Arabic novel that paints a painful picture of the realities for Palestinian people after the Nakba in 1948, and for those under apartheid in the succeeding decades. The first story follows a nameless Israeli soldier as he patrols the desert, kills a Bedouin group, takes a surviving woman, has his way with her, and then kills and buries her.

The second story follows a modern-day Palestinian journalist who reads an article by an Israeli writer and becomes obsessed with the story of the female victim from the first story. She sets out to find more information about the woman and the events of her death. It’s a heart-wrenching story about the tragedies of occupation, the drawing of borders, and cultural genocide.

In the first story, the anonymous victim’s voice is removed; she has no choice and no agency. In the second story, we witness attempts at reclamation, as we hear our protagonist’s inner thoughts and feel as though our quest for truth is also one of justice and revenge. Glimpses of inspiration can be seen amongst the cruelty and tragedy of this immaculately presented, difficult, and nuanced tale.

Buy a copy of Minor Detail here!

Breasts and Eggs by Mieko Kawakami

Translated by the Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd

In its original Japanese publication, Breasts and Eggs was a novella. This expanded version, split into Book One and Book Two and translated into English by Sam Bett and David Boyd, is about three times longer, with Book Twobeing twice the length of Book One.

In Book One, we see the world through the eyes of Natsuko, a thirty-year-old woman living alone in a Tokyo apartment and working tirelessly in her spare time to become an author. The story follows a weekend visit from her older sister, Makiko, who brings along her young teenage daughter Midoriko.

Makiko’s main reason for visiting Tokyo from Osaka is not really to see her sister so much as it is to consult a plastic surgeon about breast enhancements. Book Two is a very different beast, measuring twice the length of Book One and slowing its pace to reflect its protagonist’s age and emotional place in life.

Natsuko still lives in Tokyo, is still in touch with her sister and niece (though they exist only at the periphery this time around), and she has finally found herself where she wants to be: paid to read and to write full-time. Natsuko is far from satisfied, however. There is a slow, creeping need that is slowly closing in on her: to have a child of her own.

Breasts and Eggs is two books in one, each considering and exploring womanhood and motherhood from a broad range of perspectives. Book One is a punk and angry wolf howl, an attack on patriarchal standards and restrictions of beauty, womanhood, and femininity.

Book Two is a slower, calmer, layered conversation about the power of womanhood; her rights and her roles and her choices and her actions. It offers no one answer but, rather, asks us to consider the idea that being a woman means being yourself. Mieko Kawakami now sits as my favourite Japanese author, making her one of the most exciting women in translation of today in my opinion.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Flights by Olga Tokarczuk

Translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft

Amongst all the great women in translation, Polish author Olga Tokarczuk is perhaps the most famous and most celebrated, having won the Nobel Prize in Literature and being a staple of the Booker International Prize. Tokarczuk first gained prominence in the world of translated fiction with her novel Flights, which also skyrocketed Jennifer Croft into the pantheon of great literary translators.

Flights won the Booker International Prize 2018 and remains this writer’s favourite Tokarczuk novel to date. In Flights, our narrator is a nomadic woman who moves from place to place and muses on the philosophy of doing just that. She considers motion, mortality, stagnancy, and flux.

But as she does so, we are also thrown into other disparate tales that are narratively disconnected by thematically interlinked. These tales travel through time and space to show us different lives lived. The most prominent of these tales is the journey of Chopin’s heart after his death, being transported from Paris to Warsaw.

There is nothing in the world like Flights, and it cemented Olga Tokarczuk as one of the great women in translation of the literary canon.

Here Be Icebergs by Katya Adaui

Translated from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey

Katya Adaui is a Peruvian author who has studied in New York, Paris, and Beijing. Here Be Icebergs is a short story collection that examines the nature and messy complexities of family life. Narratively, these stories are fascinating. They mimic how we related to and talk about our families: random, biased, out-of-order stories and opinions about the people we love and hate.

The stories are tiny little vignettes; glimpses into the minds and memories of people with difficult family dynamics, traumas, and haunted memories.

These stories so closely reflect not only how we experience life with our parents, sisters, friends, and neighbours, but also how we relate those stories to one another; the lies we tell ourselves and the fears we experience alongside our experiences.

There’s power in the minimalism here. There is so much left unsaid, just as there is when we discuss our own families. There is also equal attention given to found family as there is to blood family. Few writers are able to capture the rough complexity of family in the way that Adaui has with Here Be Icebergs.

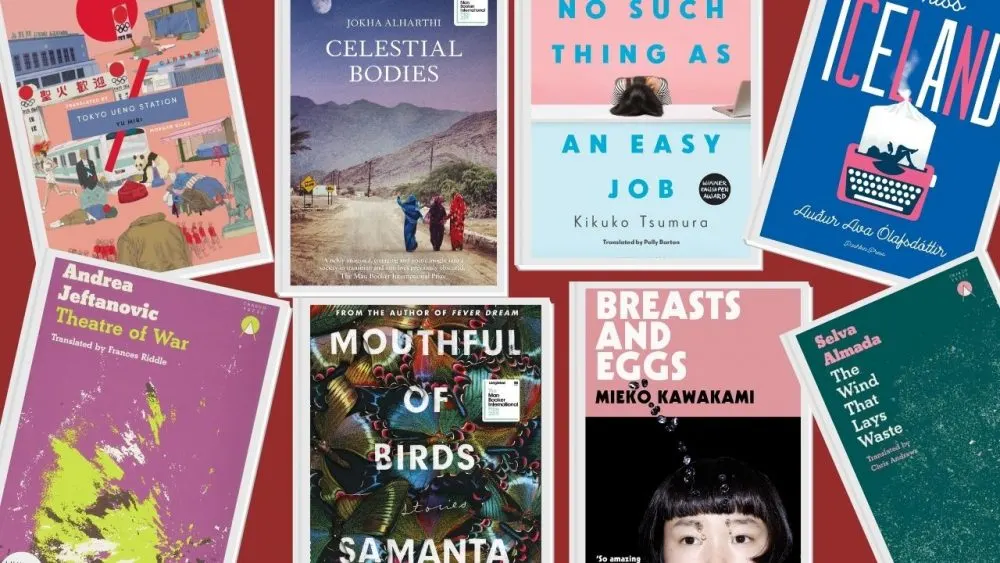

Miss Iceland by Audur Ava Olafsdottir

Translated from the Icelandic by Brian FitzGibbon

Miss Iceland begins lyrically, with hope and volition, takes us through a grounded story that is so upsettingly bleak and real, and ends with a series of complex choices which lead to an unsatisfying resolution. All of this makes it sound like Miss Iceland is a bitter disappointment, but it isn’t. It is the embodiment of bitter disappointment for women writers, not just in Iceland in this one decade, but in every nation in every decade.

This book is the story of every woman full to bursting with artistic expression and marvellous potential who is quashed by meaningless patriarchal rules born out of fear, hate, aggression, and sadism. Miss Iceland was born out of a concoction of bitterness and realism. It’s a story of countless women burdened with what they don’t want, and unable to have what they should be allowed, what they desire, what they deserve.

Hekla is a protagonist with heart and teeth, a woman we grow to love and admire, a woman trodden on by a world so ordinary and unkind. It’s a beautifully written, tightly translated, quickly paced tale about good people in a bad world. Many of the best women in translation are feminists fighting the patriarchy, and Audur Ava Olafsdottir is no exception.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

The Wind that Lays Waste by Selva Almada

Translated from the Spanish by Chris Andrews

The Wind That Lays Waste is the book that I’ll be keeping in my back pocket to pull out when I inevitably find myself less than charmed by whatever I’m reading next. It’ll be my comfort blanket. Like other books that have changed me on some ethical level – books like Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World and Jung Chang’s Wild Swans – it’ll be one that I reach for time and time again.

The Wind That Lays Waste is a tale of morality presented from two dark extremes, both of which come from a place of fear and loneliness, and both of which have the power to deeply harm, restrict, and restrain. It’s a ripping yarn at its simplest, and a deep well of moral philosophy at its most complex. Whatever you take from this book, it’ll change you.

This was my favourite novel of 2019, making it one of the most essential books by women in translation that I could ever recomment.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Solo Dance by Li Kotomi

Translated from the Japanese by Arthur Reiji Morris

Li Kotomi is a Taiwanese author who lives in Japan and writes in both languages, making her rather unique amongst women in translation. In Solo Dance, Kotomi tackles both of her cultures; specifically their relationship to queerness. Her protagonist is a Taiwanese lesbian living in Tokyo, and Norie is carrying around a lot of trauma.

After being confronted with death at an early age, and then suffering an abusive and traumatic event after being found out as a lesbian, she now obsesses over death and lives in paranoia. While her colleagues fret over mundane and ordinary things, Norie reads books by Chinese and Japanese authors who took their own lives and develops an attraction to death as an escape.

Solo Dance is a difficult book to read, but it offers so much empathy and understanding to LGBTQ+ readers and those of us who struggle with mental illness. It’s a book about paranoia, depression, fear, bigotry, but also rebellion and retribution.

Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri

Translated from the Japanese by Morgan Giles

This is one of those rare skinny books that will be kept tucked into the jacket pockets of readers, kept close to their hearts, ready to be re-read on a rainy afternoon or a stroll through the park. Tokyo Ueno Station serves as a reminder that every human is just that: human.

This novel tells the story of a man’s life; a man born on the same day as Japan’s emperor, but who lived a life of struggle and loss before dying homeless. It is an anti-capitalist Japanese novel that lays bare the unnecessary inequalities that define modern society the world over.

Yu Miri’s novel is one of the defining Japanese novels of a generation; a rallying cry against class injustice, against capitalism and the lies of meritocracy. One of the most important novels by women in translation you’re ever likely to read.

It is a tragically honest heart-on-sleeve examination and declaration of the sorrows of modern capitalist life, and more than anything it is a wonderfully written, spectacularly translated piece of fiction, and one of the literary highlights of 2019, by Japanese women in translation or otherwise.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Magma by Thora Hjörleifsdóttir

Translated from the Icelandic by Meg Matich

Another fantastic, feminist Icelandic book is the debut novel by poet Thora Hjörleifsdóttir. Magma is a 200-page novel written in small, diary-like vignettes which record the life of a young woman named Lilja. Lilja has entered into a new relationship with a quietly toxic and emotionally manipulative man who remains unnamed.

He represents not only the toxic and gaslighting men of the world, but all toxic friends and partners tha we have suffered with in our lives, regardless of gender or sexuality.

Each tiny chapter jumps forward a little, recording a new moment or stage in their relationship, as Lilja becomes unable to leave, feeling strangely attached to him and convinced that she is in love. All the while, he controls her, gaslights her, and builds a shell of paranoia around her.

Magma is a mesmerising work of feminist Icelandic fiction that warns us all against the power and tactics used by toxic people to remove our autonomy and grind us down. An essential and relatable, if heartbreaking read.

The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg

Translated from the Swedish by Deborah Bragan-Turner

Solanas feels as though women serve as little more than window-dressing in the eyes of the sickening patriarchy. She is the quintessential radical feminist, prepared to give a man her body because flesh is meaningless, but refuses to sacrifice her mind and her art to anyone.

I felt myself fall truly in love with her as the story progressed, something which I’m sure would have sickened and saddened her, if she would have even cared at all. As a reader, I don’t often find myself loving a character in this way. But I deeply loved Valerie Solanas and The Faculty of Dreams.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin

Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell

These stories are the things you can’t unsee. They tell you things you didn’t want to know, and perhaps are better off now knowing, or perhaps not. They demand pause for thought, to unpack their meaning or simply to appreciate them. Fans of Schweblin’s novel Fever Dream will love it but this is also a perfect starting point for anyone who’s curious about short stories or surrealism.

I don’t wish to count my chickens, but Mouthful of Birds might already by the defining short story collection of 2019, and to arrive so early on, well, that’s a real kindness. Samanta Schweblin is one of the coolest women in translation, full stop, no arguments.

(Taken from our review of the book. You can read the full review here.)

Flowers of Mold by Seong-nan Ha

Translated from the Korean by Janet Hong

To say too much about these stories, to analyse and study them, is to lose something. It’s better to sit quiet and let them wash over you. They’re odd, and they know you. If you open yourself up to them, let them worm their way down your spine, you may struggle to sleep and you may find yourself turning your head twice as you walk down a lonely corridor, but it’s all worth it to experience tales of this gravity.

Flowers of Mold is unhinged just enough to make an uncomfortable noise as it opens up and all its demons spill out. Here is, undoubtedly, one of the best translated short story collections of 2019, written by one of Korea’s most unique women in translation.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

The Ten Loves of Nishino by Hiromi Kawakami

Translated from the Japanese by Allison Markin Powell

In The Ten Loves of Nishino, Kawakami, with the aid of the fantastically clever translation powers of Allison Markin Powell, has attempted to capture every possible kind of woman, lover, and partner.

It’s cynical, perhaps, to bottle love – to compartmentalise it in ten equally-sized stories about ten radically different yet eerily similar women, yet if we place ourselves in the shoes on Nishino, we see how many kinds of love we might experience in our lifetime. It’s a book that shows how love is very recognisable, but equally unknowable.

In Nishino himself, Kawakami, through move after deft move, has crafted a personality we cannot quite describe. No matter how much time we spend with him, and how many pairs of eyes we see him through, we never really know him.

It’s a testament to the beauty of change — to how much we all grow and shift and evolve throughout our lives. It also warns us of how tricky love can be, when to know someone can be so difficult. There’s the potential for endless fascination and exploration with this book. It begs for multiple reads and teases the reader with the strangeness of love and life.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

A Nail, A Rose by Madeleine Bourdouxhe

Translated from the French by Faith Evans

Each of the stories in this wondrous collection is concerned – in some way or form – with putting a spotlight on the abusive, suppressive, pathetic, and radical behaviour of the patriarchy. This is all done with absolute success through inventive, succinct, perfectly-paced, eerily surreal, and painfully vivid storytelling talent.

I hope I speak for every feminist reader in the 21st century when I say that I couldn’t be more grateful to Faith Evans for reinvigorating the life and works of this incredible writer; a woman of verve, gumption, absolute command, and power. I look forward to reading everything else that Bourdouxhe ever had to offer, and rediscovering her in a new century. A Nail, A Rose is a must-read.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi

Translated from the Arabic by Marilyn Booth

The importance by Sandstone Press, the Man Booker Prize, and the world of translated literature at large to give more than just a chance, but in fact a great new stage, to Arab literature, cannot be understated. 2019 was a tremendous year for fiction from the Middle East.

At a time when Islamophobia is worsening, when political strife is becoming more bloody and blind, to have a light being shone on great Arab literature is heart-warming. It gives hope, as the arts often do during darker times. Celestial Bodies, right now, is at the centre of that literary stage, and I’m glad it is. The book is a teacher to the readers of the West about life in Oman today.

It is full of wonderful insights into Omani traditions, superstitions, and beliefs (“the newborn’s … fingernails which were not allowed to be clipped lest she becomes a thief in her future life”).There is so much that this book can do to educate us and allow us to enjoy Arab literature.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Arid Dreams by Duanwad Pimwana

Translated from the Thai by Mui Poopoksakul

This collection of stories flows incredibly well; often with short stories, you can be starkly torn from one story you didn’t want to leave and thrown into another where you don’t care about the characters as much — this can be frustrating. However, with Arid Dreams, you genuinely believe that these characters are from the same world, both physically and mentally, and never for a moment is it jarring, making for an honest-to-god page-turner.

“We coexisted in close proximity on this planet. Nevertheless, we led a solitary existence.”I really hope we all get to read more of Pinwana in the future.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun

Translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette

Thirteen Months of Sunrise will have you witnessing everything from fleeting love, bonded by shared knowledge and culture, to death and those things left unsaid. Like these stories, life, and that of those around you, is fleeting and must be cherished.

Anyone looking for a short read that will leave them feeling like they’ve truly experienced the life of another, or wishes to immerse themselves in a culture and voice that really should be more explored, then Thirteen Months of Sunrise is a perfect choice, penned by an important voice amongst Arabic women in translation.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

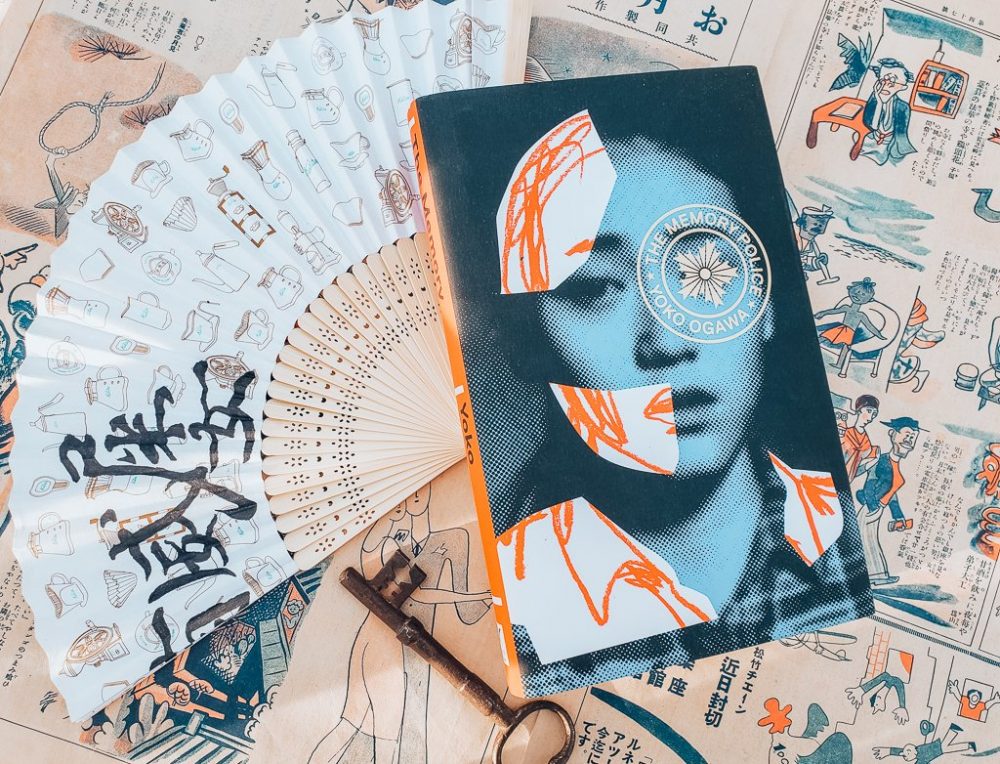

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa

Translated from the Japanese by Stephen Snyder

The Memory Police is set on a nameless island of almost entirely nameless people – a popular practice in modern Japanese literature. On this island, things disappear at random.

What this means is that people on the island will often wake up to find something either vanished out of existence, like roses, perfume, or ribbons; or things still physically exist but they no longer work or be used, like the only ferry which can leave the island.

Once something has disappeared, it is soon after forgotten by almost everyone on the island, and then they may go on with their lives, unburdened by the loss of the disappeared thing. Two kinds of people do not forget, though: the Memory Police, and a small minority of civilians who are taken away by the Memory Police if it is discovered that they are failing to forget what has disappeared.

The Memory Police is a juggling act which sets readers up with a spectacle of a concept: something strange and unsettling, something obviously dystopian and thematically intriguing, before drawing out its performance a little but all the while encouraging you to fall for its protagonists in a true and meaningful way.

At last, it enters deeply unsettling territory that will have you frantically turning pages to see how it could possibly end.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung

Translated from the Korean by Anton Hur

One of the coolest books by women in translation to come out in recent years is Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny: a short story collection that checks off almost every genre imaginable.

Beginning with a few twisted tales of gruesome and borderline-hilarious body horror, Cursed Bunny soon gives way to tales of science fiction and fantasy. Fairy tales and fables; romance and sex; stories of monsters and ghosts and people and poop.

Sometimes inspired by Bora Chung’s own experience as an academic, professor, and translator of Eastern European and Russian literature, the stories here shock and disgust, inspire and romance readers, all in equal measure. These stories are funny, dark, surreal, and grounded.

No literary stone is left unturned here in this collection of Korean short stories. There is something here for everyone, no matter the kind of reader you are.

Buy a copy of Cursed Bunny here!

The Collection by Nina Leger

Translated from the French by Laura Francis

Jeanne collects and mentally catalogues the images of men’s penises. She gives no rhyme or reason for her habit. Or is it a hobby? A job? An obsession? Even that much is unclear. It is merely a collection. For 160 pages of The Collection we the readers follow Jeanne’s routine, all of which is centred around sex, sexual organs, and the sexualising of everything around her. But why? To what end?

As you begin your journey with The Collection, you’ll be struck by the vivid yet surreal strangeness of it all. So much of the books opening pages are dedicated to the sensational details of male genitals: sight, smell, taste, texture.

We are involved intimately with the fascination which Jeanne has with the penis, and her obsession with creating what she calls a ‘palace’ in her mind of phallic images.

She collects these images by obsessively yet meticulously following a well-weathered routine of bringing faceless, nameless men with her to a hotel room and having her way with them. Her fetish is not so much with sex but with the penis itself. This is our first introduction to Jeanne. Is it undeniably intriguing and unsettling all at once.

The Collection is as much a protest as it is a story. As a protest, it shines a light on the weak and tired tropes of heroines in literature; it demands an apology from the writers who have normalised hysteria in women, wounded and victimised women, strange and slutty women, and women who must be ashamed and apologetic for their lives and their choices.

As a story — one of the most original novels by French women in translation — it’s a thrilling, surreal journey through the wonderful mind and daily life of a woman who puts her kink first: Jeanne has a collection to build, and she isn’t wasting time. Jeanne is a celebration of the kinds of things that exist “behind closed doors”.

(Taken from our review of the book. Read the full review here.)

The Sea Cloak by Nayrouz Qarmout

Translated from the Arabic by Perween Richards

What we often need as much as hard political facts and details is true connections to those innocents who suffer the most. We debate these topics while forgetting that they are people – not chess pieces.

Through The Sea Cloak — a collection of eleven biting and honest Arabic short stories — Nayrouz Qarmout offers that connection. She allows us to replace these pawns with people. She opens the door between us and Palestine, stretches out her hand and says, “Here, come see our lives for yourself.”

Qarmout herself, a feminist journalist and women’s rights campaigner based in Gaza, grew up in a Syrian refugee camp. She has experienced life for Palestinians in almost every way that it can be experienced.

As authorities on family, women’s rights, and childhoods in Gaza go, she is arguably the foremost. And here, in The Sea Cloak, she channels her knowledge, her emotional experiences, and her insights into a collection of human stories that are, while undeniably political, more concerned with family life and childhood. Though of course, these being the lives of Palestinians, family life and childhood are inextricably tied up in politics.

The Wandering by Intan Paramaditha

Translated from the Indonesian by Stephen J. Epstein

The Wandering is a dense Indonesian novel of branching paths inspired by the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure books of old. But while those books were fantastical, and written for kids to experiment with their own imaginations, The Wandering is a story of migration, of searching the world for happiness and hoping that it will be found over the next page (or if you turn to page 42).

The narrative in The Wandering is written in the second person, with all the action directed at ‘you’, the reader. But you are no blank slate here; in fact, you’re a fairly defined protagonist.

‘You’ are a woman, aged 27, Indonesian, and living in Jakarta as an English teacher. When the Devil comes to you, you lash him to your bed and make him your lover for a few weeks until, eventually, you use him to gain access to the wide world.

The Devil provides you with a pair of red Dorothy shoes and magics you away to New York. Specifically, a cab on the way to JFK, with a ticket for Berlin.

You are disorientated and, when you arrive at the airport, you realise one of your red magic shoes is missing, and you must make your first choice: continue on to Berlin, return to NYC and find your apartment, or report the missing shoe to the police. Each thread leads you to more threads, and there are fifteen possible endings to your story.

For more wonderful women writers, check out our favourite East Asian writers.