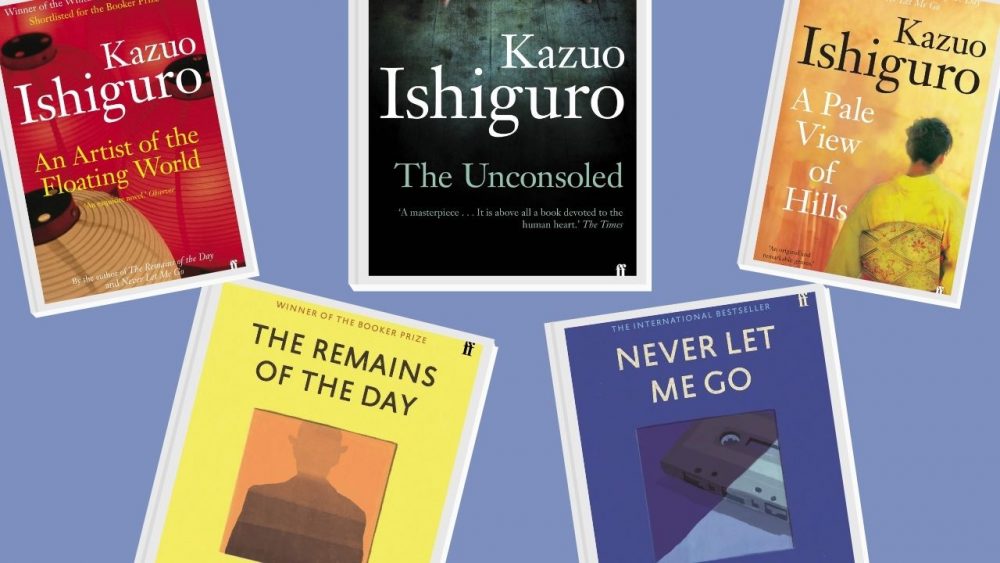

Nobel Prize-winning author Kazuo Ishiguro is one of the world’s most revered and beloved living authors.

His books have been adapted to the big screen, have established him as king of the unreliable narrator, and have explored complex but relatable and human themes.

The Japanese-born British author has never written a bad book. Every one of his novels is a masterpiece. That said, some are stronger, more successful masterpieces than others.

So, if you’ve ever wondered where to start reading Ishiguro, or what Ishiguro’s best books are, here are all of Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked from worst to best.

Kazuo Ishiguro Biography

Before we look at Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked, it’s worth exploring the life of Kazuo Ishiguro, an author who has lived quite a romantic life, and who showed his genius rather early.

Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Japan — specifically, the southern city of Nagasaki. When he turned five years old, his parents moved to the UK and settled in Guildford, Surrey.

The effects of his Japanese background and British upbringing can be seen in the focus of his novels on both Japanese and British settings and characters.

Ishiguro’s first two novels are set in Japan and feature Japanese characters, with his first novel, A Pale View of Hills, moving its narrative between present-day England and a Japan of the recent past.

Ishiguro’s literary influences, at least as a young author, were more Western than Japanese, and he has remarked on how the Japan we see in A Pale View of Hills and An Artist of the Floating World are, to a point, fantastical.

Those books are built out of an idea of Japan which Ishiguro had in his head, rather than any first-hand research and experience.

A Pale View of Hills was published by Faber before Ishiguro was thirty years old, and he has gone on to write a total of eight novels and a book of short stories (all published by Faber) across a career spanning more than three decades.

A 1993 film adaptation of Ishiguro’s book The Remains of the Day, starring Anthony Hopkins, Emma Thompson, and Christopher Reeve, was nominated for eight Academy Awards.

In 2017, Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 2019, he received a knighthood for his services to literature. In 2020, his daughter Naomi Ishiguro had her first book of short stories published by Tinder Press, titled Escape Routes.

Let’s now move on to a discussion of Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked, what they’re all about, their themes and characters, and why every one of his books is a masterpiece.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s Books Ranked: From Worst to Best

Now that we’ve got a brief biography of Ishiguro covered, here are all of Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked (excluding his short story collection, Nocturnes) beginning with his weakest novel and ending with his very best work.

When We Were Orphans (2000)

In 2005, I moved to Shanghai. The Buried Giant had just been published so I threw that, and a paperback copy of When We Were Orphans, into my suitcase.

Reading a book set in a place before or after you move there is a very satisfying experience, and When We Were Orphans is set in the Shanghai of the past.

The novel follows a British detective named Christopher, who grew up in Shanghai and is lured back to solve a case. His return to Shanghai is set against a backdrop of war and invasion, as the Japanese encroach on Shanghai.

When We Were Orphans isn’t a bad book. Ishiguro doesn’t write bad books. It is, however, his weakest novel. It doesn’t have in its heart any of the magnificence that makes his other novels so brilliant.

His infamous unreliable narrator, his themes of memory and time. These things are either missing or undercooked here.

If a new reader didn’t know any better, they might suspect When We Were Orphans to be Ishiguro’s debut novel (rather than what it is: his fifth book), given how ragged and amateur it reads in comparison to his other works.

All of this leads to the fact that, despite it still being a good enough novel in its own right, When We Were Orphans is the weakest book when talking about Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked from worst to best. It only gets better from here.

The Buried Giant (2015)

As a reader who cut their teeth on fantasy novels, it was The Buried Giant which first drew me to Ishiguro. While it isn’t his best novel, it does represent an interesting departure from his usual settings and character types.

Ishiguro likes to write about Japan and Britain. The Buried Giant is, arguably, his most British novel. Set in an alternative medieval world of Arthurian legend.

The story follows an elderly couple named Axl and Beatrice, who have suddenly remembered that they have a son.

The two suffer from a kind of memory loss that seems to be tied to a fog that has settled on the land. The bulk of the novel is a Hobbit-esque journey across the land in search of their newly-remembered son.

The Buried Giant almost pokes fun at that mechanic which Ishiguro is most famous for: the unreliable narrator. If our narrators cannot be trusted to remember anything, how reliable can they ever be?

It’s a fun approach that makes this a more simple and light-hearted Ishiguro novel.

While it doesn’t reach any great heights, The Buried Giant is far from a bad book. On a list of Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked, it might sit near the bottom but it certainly isn’t a rubbish novel. None of his books are.

A Pale View of Hills (1982)

Ah, this book. A Pale View of Hills was Ishiguro’s debut novel. It’s a book I have very fond memories of, and it is one that doesn’t get talked about enough.

A Pale View of Hills is often overshadowed by Ishiguro’s most successful books, the ones that received film adaptations. It’s one that very much deserves your attention, though. I hope I can convince you why.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s debut novel tells the story of Etsuko, a Japanese woman living alone in a rural English cottage.

Her eldest daughter has committed suicide and, during a visit from her youngest daughter, Niki, Etsuko tells the story of how she ended up leaving Japan for England.

Etsuko’s story is one of love and friendship. It focuses on her friendship with another Japanese woman who has dreams of moving to the US. Motherhood is also a strong narrative thread through this novel, with Etsuko and her friend both being mothers with eyes on the future.

What really makes A Pale View of Hills such a memorable read is its jaw-dropped and immensely satisfying twist ending (which I will not spoil here).

This is the book that cemented Ishiguro as king of the unreliable narrator, and it still holds up as one of his best books.

I’m very happy to put it dead centre on a list of Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked. It’s not his best but it is far from his worst.

The Unconsoled (1995)

The Unconsoled is Ishiguro’s longest book. It is a Kafkaesque anxiety dream of a novel which follows the strange and surreal story of a concert pianist named Ryder, who ends up in a nameless European city.

He is there to put on a performance.

In the days between his arrival and the concert, Mr Ryder is thrown into an ocean of strange requests, appointments, and demands from people who are, as the title suggests, unconsoled. He is loaded with responsibilities he does not understand, and did not expect.

The Unconsoled is an enormously polarising novel, which was met with praise and disdain from critics upon its release, and those extreme reactions have remained reliable in the years since.

Most readers of The Unconsoled are either convinced by its genius or abhorred by its frustrating elements.

This is a 530 page novel that plays out like an awful dream. I mean that quite literally: Ishiguro uses dream logic to layer events and places atop one another.

A stranger Ryder meets early on in the book is a woman he soon realises is his wife. A building he drives far to get to is suddenly attached to the one he left.

The dream logic is very Kafka-inspired, as Ryder moves in circles and is forced from appointment to frustrating appointment, doing favours for people he doesn’t know.

The Unconsoled is taxing and frustrating, but if you allow yourself to move with it, you’ll be charmed by its humour and absorbed by its themes.

Those themes mostly concern themselves with a life wasted (Ishiguro’s most popular theme, found in many of his novels) and the anxiety that comes with anticipation, with burdens of responsibility, and with doubt.

The Unconsoled is certainly not for everyone. I personally enjoy the dream logic, the Kafkaesque tone and events, and the bleak humour of the novel.

But I also felt frustrated by its length and thought that it outstayed its welcome. Sometimes less is more. For this reason, it sits above his worst but below his best works.

Klara and the Sun (2021)

Ishiguro’s newest novel, following The Buried Giant, is Klara and the Sun.

This is a science fiction masterpiece that tells the story of Klara, an Artificial Friend (or AF). The purpose of an AF is to be a companion to the teenager who selects them.

Klara begins her story in a store in an unspecified American city. She is put on display and, through her eyes, we learn about the world — or, at least, the world as she sees it.

Klara is soon chosen by a teenage girl called Josie who takes Klara home to live with her in the countryside.

Klara and the Sun never quite reaches the searing heights of Ishiguro’s other sci-fi novel, Never Let Me Go, but it does come close.

This is a novel about love and hope. Klara’s relationship with Josie, and Josie’s relationship to her own mother Chrissie and her best friend Rick, is the glue of this book.

What makes this almost an elevation of Ishiguro’s unreliable narrator trope is Klara’s own unique perspective on the world (literally, how her robot eyes see things, and metaphorically, how she learns and comes to understand people and their relationships).

This is a very sweet and tender novel full of love in all its forms. It considers class and social groups, but it also deals heavily with love, religion, superstition, and, most importantly, how we hope; how we use hope as a method of survival.

Alongside Never Let Me Go, Klara and the Sun proves that Ishiguro’s greatest strength is observing human relationships through a variety of lenses; and he is at his best when using science fiction as a tool for exploring that to its fullest.

Never Let Me Go (2005)

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Never Let Me Go is Ishiguro’s masterpiece. His magnum opus. I can’t disagree with that statement but it is still only my third favourite Ishiguro novel.

While I do agree that it is flawless, I find the themes and characters found in my two top Ishiguro books to be stronger.

Never Let Me Go is a science fiction novel set in the modern day. It’s a novel with a central mystery that, if you’ve never had it revealed to you, should absolutely not be spoiled.

Our narrator is Kathy, a woman who works as a carer. Who or what she cares for isn’t clear. Kathy spends much of the novel reminiscing about her childhood at a secretive English boarding school called Halisham.

We become familiar with her old friends and quietly unnerved by the elephant in the room, even though we don’t know the name of the elephant or why it’s there. As the story unfolds and secrets are revealed, tragedy sets in.

Never Let Me Go is a truly astonishing work of literary magic. While it is difficult to talk about in detail, it needs to be read to be fully experienced. The less you know about its story, the better.

Ask any fan for their take on Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked, and Never Let Me Go will very likely land on top. I won’t argue against that, but it still isn’t my personal favourite. That would have to be the next one…

An Artist of the Floating World (1986)

To be honest, the two best Ishiguro books are fairly interchangeable. While this is a list of Kazuo Ishiguro books ranked, you can safely discard the numbers for the top two.

The reason I’ve put them in this particular order is simply: An Artist of the Floating World is my favourite Ishiguro novel, but I believe that The Remains of the Day is a slightly better reading experience. We’ll get to why in a moment.

An Artist of the Floating World was Kazuo Ishiguro’s second novel, his first novel to be set entirely in Japan, and his last to be set in Japan at all.

Its story takes place after the end of World War II and the fall of the Japanese Empire, and it follows the life and memories of an aged and once-renowned ukiyo-e painter named Ono.

Ono has had a long and revered career as a ukiyo-e artist but, when war began brewing, he strayed from the teachings of his master and turned his hand to making propaganda posters.

With the war over, Ono and his works are now a symbol of embarrassment. His family, neighbours, and old friends look at him with shame and embarrassment.

An Artist of the Floating World is a masterpiece, not only in its setting and its themes of shame, political corruption, and time’s ability to change us. It is also a masterpiece of character writing and perspective.

We see the world through Ono’s eyes, making him a sympathetic character, and yet we also grow to be repulsed by him as the story unfolds.

There is a persistent tug-o-war in our hearts as we struggle to sympathise with Ono while also being trapped in his mind and his memories.

An Artist of the Floating World presents a challenge of perspective and sympathy rarely explored so well in literature. It is an absolute masterpiece of modern fiction and my personal favourite Kazuo Ishiguro book.

While it is my favourite, however, on a list of Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked, it still doesn’t quite make the top.

The Remains of the Day (1989)

Anyone’s list of Kazuo Ishiguro’s books ranked is likely to have this (or maybe Never Let Me Go) at the top.

As mentioned above, The Remains of the Day shares an awful lot of themes, and a similar central protagonist, with An Artist of the Floating World. I’m not the only person to view the former as a kind of prototype for the latter.

And, while I personally prefer the prototype for its settings and extra depth of character, The Remains of the Day is ultimately the most polished, refined, and complete novel. It is, in fact, Ishiguro’s very best novel.

The Remains of the Day begins with our protagonist and narrator, a butler named Stevens, setting out on a road trip. He has worked at Darlington Hall for years and his new employer, a nouveau riche American, happily encourages him to take a vacation.

Stevens plans to reunite with Darlington Hall’s former housekeeper, a woman whom he clearly had deep feelings for. Stevens, however, has always been married to his job.

He is a rigid, unmovable, conservative traditionalist with a particular attitude towards life, work, and class.

Stevens and Ono have an impressive amount in common: both are men stuck in the past, corrupted and dismantled by their politics, their attitude towards life, and their inability to move forward as time itself does.

What makes The Remains of the Day the better of the two is how much more of a clear-cut character Stevens is. He is just as complex but easier to read.

There is less ambiguity in this book, and so it feels more accessible without sacrificing any of the depth of theme and tone that made An Artist of the Floating World such a masterpiece.

Ultimately, these two are very similar books that are equally impressive, but The Remains of the Day builds on the themes of its predecessor to craft a neater, tidier tale. This is Kazuo Ishiguro’s best book.