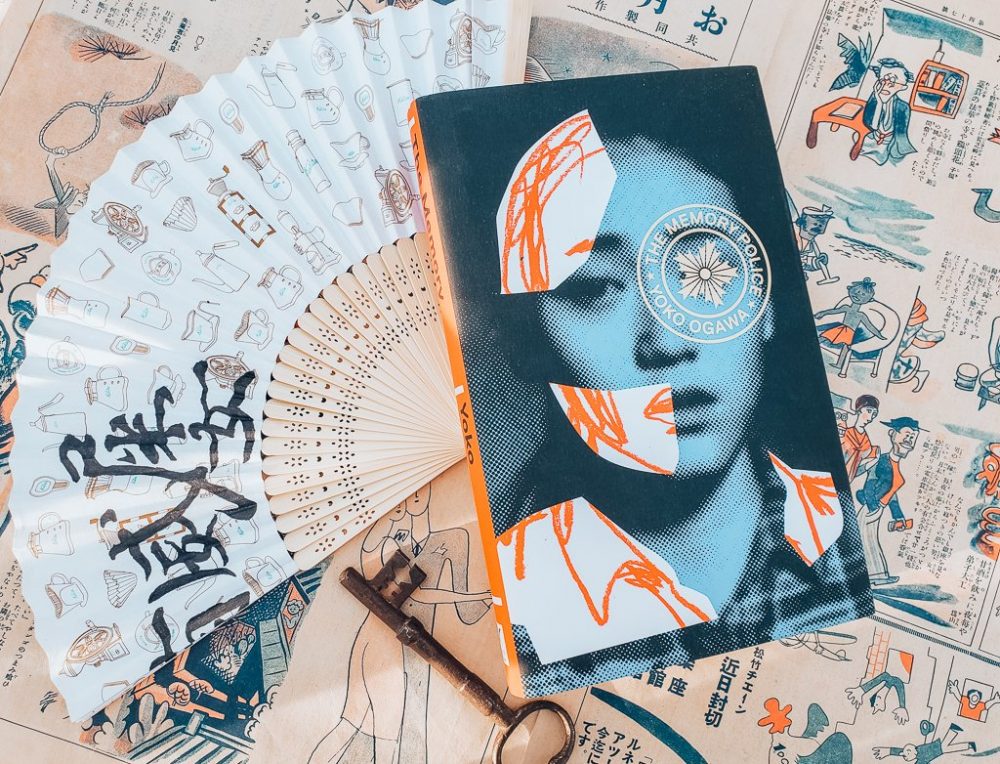

Translated from the Japanese by Stephen Snyder

The state of the world as it stands today, with regressive government bodies, the existence of oligarchies, state-controlled media, and a frightening amount more, all makes it both easier and harder to create new dystopian fiction. Easier in the sense that you can throw a dart at a map and come up with an absurd alternative or future world based on that nation’s politics.

Harder because the world is doing it for you. With The Memory Police, Yoko Ogawa has circumvented all of this by building a world vague enough to be interpreted in multiple ways, and absurd enough to be almost enjoyed as an apolitical novel – though I wouldn’t recommend that. It is political, after all, and it is powerful.

The Memory Police

The Memory Police is set on a nameless island of almost entirely nameless people – a popular practice in modern Japanese literature. On this island, things disappear at random. What this means is that people on the island will often wake up to find something either vanished out of existence, like roses, perfume, or ribbons; or things still physically exist but they no longer work or be used, like the only ferry which can leave the island.

Once something has disappeared, it is soon after forgotten by almost everyone on the island, and then they may go on with their lives, unburdened by the loss of the disappeared thing. Two kinds of people do not forget, though: the Memory Police, and a small minority of civilians who are taken away by the Memory Police if it is discovered that they are failing to forget what has disappeared.

Our protagonist is an author whose mother kept mementos of things that have disappeared and was eventually taken away by the Memory Police. Our author, however, does forget and lives in fear of what may vanish next.

“If you read a novel to the end, then it’s over. I would never want to do something as wasteful as that. I’d much rather keep it here with me, safe and sound, forever.”

After the story opens with our author’s childhood and the establishment of the world she lives in, the majority of the tale focusses around her and two men: the former ferryman, a kindly and helpful old man; and her editor, another of the rare breed of people who never forgets the things that have disappeared.

When the threat of the Memory Police grows, our author finds a place to hide her editor away, and there looks after him as the winter grows harsher and more things continue to disappear from their world, shifting their lives in a more frightening way each time.

The Memory Police triumphs at instilling a sense of anxiety in its readers from beginning to end. A kind of low-lying perpetual nervousness that occasionally spikes and never fades. This is achieved by drawing out the mystery surrounding the disappearances of things and the identity of the Memory Police, as well as keeping us in suspended fear of what will disappear next, wondering how far the disappearances can go and how their world must surely, eventually, collapse.

“Silence fell around us all, as though we were steeling ourselves for the next disappearance, which would no doubt come – perhaps even tomorrow.”

All dystopian fiction points its finger at something; is based on the author’s concern – and thus the concern of the whole society in which they exist – about what conclusion the issues of the day might lead to. Some dystopian novels, such as Nineteen Eighty-Four, aim to warn us of the current political trajectory we are on, while others, like The Handmaid’s Tale might take real-world issues concerning human rights, religious oppression, and media control to a logical extreme that frightens its readers.

The Memory Police exists in an Orwellian world, but its tone and story is far more extreme and less grounded. In fact, it might be fair to call the world of The Memory Police absurd, as there is no logic, science, or even mysticism that explains away the phenomenon of disappearance within the novel. It’s all vagueness and strangeness.

As for what The Memory Police stands for, that is very much up to you. There’s an ambiguity to the story and its themes which might lead the reader to interpret it as a commentary on – and a warning against – state control of our media, our history books, and our schools systems, as is most obviously the case in countries like China, but can also be seen in supposedly “free” nations like the US and the UK.

Though the book could also be less cynical than that, and more an attack on our collective laziness. We have forgotten our animal roots: how to hunt, forage, fend for ourselves; we are fat, lazy, and take our supermarkets, our electricity, our cars, and our jobs for granted. And what happens when these things disappear? Will we starve or will we adapt?

The Memory Police takes no firm stance either way, and its cleverness lies in being potentially read either as a comment on the state forcing us to forget or misremember things like Tiananmen Square or even Boris Johnson’s Brexit bus; or as a warning against our willingness to forget skills and knowledge in favour of idleness and automation. And, of course, there exists a third option: enjoy the novel as a terrifying and exhilarating yet slow-burning thrill ride of a story.

“‘And what might happen if words disappear?’ I whispered to myself, afraid that if I said it too loudly, it might come true.”

Putting all of this cleverness and anxious tension aside for a moment, however, The Memory Police is not a perfect dystopian novel. In fact, it suffers from similar problems to 2018’s big dystopian Japanese novel: Yoko Tawada’s The Last Children of Tokyo. Both novels suffer from a true advancement of plot and are very much books of concept. Each engages us with a fascinating and truly chilling world but does little to guide us through it with a progressive story.

The Memory Police does fare better, however, with a truly empathetic protagonist and stakes which are felt far deeper. The thing I adore Yoko Ogawa for the most is her complex yet subtle building of relationships, as best seen in her masterpiece: The Housekeeper and The Professor. These wonderfully crafted relationships are certainly present here, as well. And so, despite a plot that stagnates a little as it goes, The Memory Police is saved by its dedication to building and strengthening intense personal intimacies between its characters.

Conclusion

The Memory Police is a juggling act which sets readers up with a spectacle of a concept: something strange and unsettling, something obviously dystopian and thematically intriguing, before drawing out its performance a little but all the while encouraging you to fall for its protagonists in a true and meaningful way. At last, it enters deeply unsettling territory that will have you frantically turning pages to see how it could possibly end.

There are certainly issues with tone and pacing, and yet you could not say for a moment that The Memory Police ever allowed you to relax; the fear of the unknown and the quiet anxiety the book infects you with never go away. And this book has a refreshing take on the dystopian formula, with an original concept and a message vague enough to encourage debate, and yet strong enough to have your brain ticking over for days after you put it down, until the urge to pick it up again searching for answers you might have missed becomes too much to bear.

It’s safe to say Yoko Ogawa has done it again: she has shown why she’s one of the best writers Japan has; how she takes a genre or an idea into her hands and moulds it into something human, something frightening, something raw, and something wholly new.