Before I lived in Tokyo and Seoul, I lived in Shanghai. Expats and locals alike in Tokyo and Seoul have joked with me more than once about the harshness of Chinese culture and the unpleasantness of life there; jokes such as: ‘On the Seoul subway, keep your voice down. You don’t want to be a Chinese tourist!’ and ‘I know I could save more money living in China, but I’m not that desperate!’

These jokes are always made by people who have not so much as visited China. And so, when I hear their jokes, a word defending China leaps onto my tongue, but I always stop myself with the thought: Well, they’re not wrong. China’s tough.

But why is China tough?

Before I get into the why, let me admit that I was not kind to China when I lived there. The rough skin that one needs to survive in Shanghai did grow on me in some ways as I learned to ignore my British instincts and cease queuing on the subway platform, otherwise risk never getting on a train and soon starving to death.

But it also failed to grow in other ways, as I found myself close to tears at the sight of cold-blooded middle-aged women selling caged, drugged, dying Labrador puppies to vulnerable and pitying tourists on street corners. As a result of this half-coarse, half-softened shell I had grown, I became angry.

Furious. I screamed and shouted in frustration at so many difficult situations on a daily basis, and as a result my relationship with my partner, and my own mental and physical health, suffered. I slept too much, I got fat off comfort foods, I grew complacent and stopped looking after myself. China beat me down, and I was lashing out at it in kind. But did China deserve it? Does it ever?

I found the answer to that question, and the previous one, in a book.

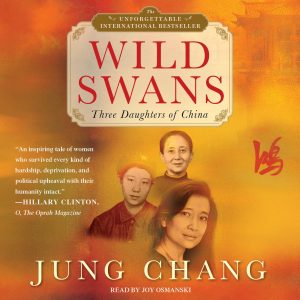

One year after leaving China behind, I read Jung Chang’s Wild Swans. Jung Chang lived out her childhood during Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, the famine that it led to, and the subsequent Cultural Revolution. She tells this story, as well as that of her mother, a communist revolutionist and member of Mao’s Red Army, and her grandmother, the concubine of a Manchurian warlord.

Chang has crafted a guide to the struggle, survival, and victory of the Chinese people during the twentieth century in the form of a grand biography spanning three generations of incredible women: Three Daughters of China.

The very first change in me and my perception of China came about early in Wild Swans, as Chang describes her grandmother undergoing foot binding, and in fact being part of the last generation of Chinese women to have it done. Foot binding was forced upon women in China for several hundred years as a palpable and, most would argue today, disgusting example of male dominance over women.

Read More: A Complete Guide to Living and Working in China

It is said that one of the major reasons for foot binding was that men at the time found the sight, and even the smell, of curled and broken toes and feet erotic; sexually arousing, even.

This form of misogynistic torture is arguably, even by young generations of Chinese men and women today, abhorrent, but it does throw into sharp relief both the pain felt by women in China for so long, and the steps the entire nation has taken to remove themselves from acts such as this.

After reading about Jung Chang’s grandmother, I experienced the first of many imaginings of myself back in Shanghai.

I was angry at an elderly woman for aggressively shoving past every young person in the supermarket queue to get to the front but, after reading this book, it’s much easier to imagine what she, and certainly her mother and grandmother, had been through in their lives. This aggressive old lady at the supermarket is aggressive because she is a product, and a survivor, of terror, torture, abuse, humiliation, poverty, and so many other horrors.

I had to respect her, but I didn’t, and I wish I had. We all know the sudden rush of rage we feel when a stranger cuts in line in front of us, or pulls out suddenly as we’re driving along; these people are arseholes. We instantly brand them that.

That person isn’t a person with a life of their own, and feelings, and a family; they’re just… an arsehole. But what if that person has lived through a famine and survived? They’re not just some nasty woman in the supermarket queue. They’re a survivor.

But is that enough to excuse them from bad manners? And what are bad manners, exactly? How do we define them? That question was answered by Jung Chang’s mother and the Cultural Revolution.

Not Escaping Cultural Stereotypes

When we read biographies and histories, there will be at least one moment in every chapter that we dog-ear, or jot down, or just stop and shout to our partner in the next room, ‘Hey, listen to this!’

These are often facts we either forget or are useless outside of a pub quiz. But one of these little titbits aided my understanding of not only the public behaviour of the average Chinese person, but also the way that I personally view manners, and the very Western cultural concept of manners themselves.

The cultural stereotype of us Brits is, I’m well aware, politeness and meekness. And, as anyone who is literally from anywhere will surely know, it’s very difficult to agree or disagree with stereotypes about one’s own country. ‘Hey, Mr American, is it true all Americans are fat?’ ‘Uh, some of us are, I guess. I’m not. My dad is.’ It’s difficult to say, because you are not your country, and you haven’t surveyed your country.

That being said, it’s safe to say that most Brits highly value manners, just as most Americans value positive behaviour. If a person says ‘thank you’ to a Brit, but that Brit gets the feeling that the ‘thank you’ was not said quite earnestly enough, they will remember it; they may even bring it up to their friends later on at the café. ‘I think she was being sarcastic, you know? The nerve!’

Understanding Myself

And so I have had to admit that, though I’m as far from a patriot as one can be, cultural upbringings cannot be ignored. And, as a result of this, I care deeply about public manners, right down to the marrow of my bones. I care so much about how loudly someone talks on their phone or if they hold the door open for the next person as they leave Starbucks. Someone lacking in this behaviour will cause my emotions to flip in the blink of an eye.

I bring all of this up for a reason: the average person in Shanghai lacks almost all of the manners I have learned to expect. Holding open doors is not the done thing; covering your mouth when you cough is not deemed important; hawking up loudly and spitting on the street is encouraged. These behaviours are difficult to reconcile for a stiff-lipped, grumbling, miserable Brit like myself.

And so I would pompously raise my head at the pub on West Nanjing Road on any given evening and say to my expat friends, ‘You know, people here are so bloody rude!’ Of course I know now that there’s nothing ruder, more bad-mannered, than a naïve expat coming out with a comment like that. And it was Jung Chang’s mother in Wild Swans who helped me see this.

During the Cultural Revolution

Mao made some rather large changes to his country. One important example, as explored in Wild Swans, was the branding of intellectuals (such as professors) and artists (such as poets and writers) as ‘class enemies’ who were promptly and mercilessly hunted down, beaten, and arrested by members of Mao’s Red Guard.

The first half of the twentieth century gave rise to a large number of rather famous fascistic leaders that took the ideas of Marx – and later Lenin – and bastardised them to meet their own end.

This censorship of intellectuals was part of Mao’s vision of eradicating all things bourgeois from his country. And one seemingly minor – but critical for my purposes here – offshoot from this culling of ‘class enemies’ was Mao’s encouragement of his people to remove manners of any sort from their verbal and physical behaviours.

As I learned in Wild Swans, Mao deemed manners to be a pointless and useless affectation of the bourgeoisie; something that served people not at all. While this may seem trivial, I’d argue that such a small bit of behavioural training has helped transform China into what can be called a ‘me-first’ nation.

Read More: 5 Books to Read Before you Visit China

The glorious thing about China is that, in some ways, it follows and realises the American Dream better than America ever can today. In China, as Jung Chang herself demonstrates in the latter half of Wild Swans, anyone has the opportunity to make anything of themselves.

Despite the censorship and media control, paradoxically, people are free to do as they wish and be what they wish to be. But this behaviour takes guts, and a lot of cutting others down in order to reach the top.

This attitude has produced the second strongest economy of the twenty-first century (likely soon to be the first), but it has also created a nation of people who do not follow the same pattern of social behaviour that most in the west, and certainly in the UK, have come to expect from others.

While this may be an interesting history lesson, it’s also worth very simply mentioning that people do not have to behave the way that you want them to. This might be an obvious point for some, but it wasn’t for me. And, much to my shame, too often during my time in Shanghai did I find myself behaving like a missionary, calling the wonderful and fascinating and passionate people around me ‘rude’ or ‘callous’. They are no such thing. Wild Swans proved this to me.

My Purpose

My purpose here is not simply to recommend a good biography/history book (though I absolutely do), but, if I may be so bold, to also teach any current or would-be migrants (or ‘expats’ if you prefer) a lesson in humility. In some ways that are painful to admit, I wasted my time in Shanghai being appalled by things I simply could not accept, and reacting angrily to behaviour I did not understand.

One goal anyone who travels and lives abroad should have is to take the opportunity to learn. Whether that be a language, a cuisine, a religion or political system, or more broadly the simple patterns of everyday life in a place so dissimilar to that which raised and moulded us.

It can be hard for some, and easy for others. I knew many a fellow foreigner in Shanghai who never understood where my anger came from, having adapted so seamlessly to Chinese culture as they had. I also have met people in my current home of Korea who grit their teeth at the most minor irritation, and I think to myself, if you can’t ride such relaxing waves as Seoul offers, don’t even attempt China’s rough waters.

My point is that China is wonderful, and if only I had done some reading before I moved there. If only I had taken a month to study the modern history of China, to walk in the shoes of three generations of incredible Chinese women, as Jung Chang has courteously allowed me to do since, perhaps I wouldn’t have been such an arsehole.

So keep in mind that, in so many ways, harsh as it sounds, China really does suck. But you have to permit China to suck. Admire how and why it sucks. Enjoy it despite how it sucks and because it sucks.

I’d also like to add that I wholeheartedly love and cherish China. Though Tokyo is the most exciting city I’ve lived in, and Seoul the most warming and comfortable, Shanghai is the most interesting. And I do think I may find myself living in China again one day. Likely one far-off day, when I’ve hardened my skin and learned some manners. I have Jung Chang and Wild Swans to thank for helping me get to this point.