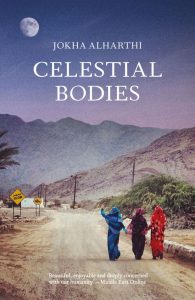

Arab literature is rising in popularity – not yet soaring, but with Celestial Bodies having just won the Man Booker International Prize 2019, we’re going to be seeing an upwards trajectory that gets steeper and steeper in the months and years to come. As an introduction to Arab literature and anyone looking to explore its riches, Celestial Bodies is a superb choice.

Celestial Bodies centres around a family in the Omani village of al-Awafi. Three sisters, Mayya, Asma, and Khawla are growing up, falling in and out of love, and raising children in a time of great cultural, economic, and political shifts in Oman.

(If you are looking to include more Arabic Literature in your life is the Arab lit blog. You can also subscribe to their journal, which we thoroughly enjoy. Or try some of the wonderful new Comma Press books, like Thirteen Months of Sunrise, The Sea Cloak, and The Book of Cairo).

A Land in Motion

Seeing the growth of Oman’s wealth, the abolition of its slave trade, and the seeping in of Western movies, language, and social attitudes – all from the inside – is compelling, to say the least. Mayya, the oldest sister, opens the book with deep heartbreak; the wound stays fresh and open even as she is ushered into a marriage with Abdallah, a rich merchant’s son.

She has no time to grieve, to find and compose herself as a woman. She is thrust into motherhood, naming her first daughter London as a subtle rebellion and a sign of the changes coming to Oman and its people.

“When we are away from home, in new and strange places, we get to know ourselves better. And that is exactly the way it is with love.”

Mayya’s sisters each suffer love in their own unique ways, but are far, far less fleshed-out characters. Their disparate ways of living with love serve more to emphasise the ways in which Omani culture is growing increasingly complex.

There is no longer one way to marry, one duty to bear, one life to live. Respect for the husband, the father, the tribe, is called into question and often abandoned. As a lesson in 21st-century Omani culture, these sisters are fine examples. However, as characters in their own right, they are flatter than paper.

The spotlight is often given to Mayya’s husband, Abdallah. Each chapter of Celestial Bodies is dedicated to a single character’s name and perspective, and Abdallah’s is the only one written in the first person. This can be interpreted as a (very successful) attempt by the woman author to shine a light on patriarchy and male self-indulgence within traditional Arab culture.

However, unexpectedly, as Abdallah’s life is explored through flashes forward to his daughter London’s life as an adult, and back to his own childhood, we see the struggles he has gone through as a rich merchant’s son. He offers us glimpses into the abolition of slavery in Oman thirty years past, and nods to the more global, dynamic, difficult, and colourful Oman that is blossoming.

For him, both the past and the future are a sad struggle, as he laments many times the fear that his wife does not truly love him. The fact that we grow to know Abdullah the most intimately is a cleverly cynical move, but we do learn to care for him all the same.

Life as a Photo Album

Celestial Bodies often feels as though it is a collection of scraps being held together with tape. This is partly due to its frequent and unforgiving jumps through space and time, between characters and moments.

Its tone shifts from joy to tragedy at the turn of a page; its characters are given no breathing – or grieving – room before being tossed aside to make room for their sister or husband to take the spotlight for three minutes. It’s a rush to keep tabs on what each character is doing, thinking, feeling, burdened with, or hopeful for at any given time. And all of this can be genuinely stressful.

“Mayya considered silence to be the greatest of human acts, the sum of perfection. When you were utterly quiet and still you were likeliest to hear accurately what others were saying.”

But then, isn’t that stress a kind of empathy for the characters? Are we being made to feel what they feel, as passengers on the ship of life, thrown around during a storm? Perhaps, and if that is the author’s intention, then Alharthi certainly succeeds – as does Marilyn Booth in translating this turbulent storm into English.

But does it make for a cohesive, pleasant narrative? Certainly not. What the story often feels like is a photo album being opened in front of us.

The author points to each photo and provides us an amusing titbit or a sad little yarn to go along with it, before moving on to the next one. Perhaps a later photo will have something in common with that first one – thematically, tonally, narratively – or perhaps it won’t.

Conclusion

The importance by Sandstone Press, the Man Booker Prize, and the world of translated literature at large to give more than just a chance, but in fact a great new stage, to Arab literature, cannot be understated. This is a tremendous year for fiction from the Middle East.

At a time when Islamophobia is worsening, when political strife is becoming more bloody and blind, to have a light being shone on great Arab literature is heart-warming. It gives hope, as the arts often do during darker times.

“Sleep was her only paradise. It was her ultimate weapon against the pounding anxiety of her existence.”

Celestial Bodies, right now, is at the centre of that literary stage, and I’m glad it is. The book is a teacher to the readers of the West about life in Oman today. It is full of wonderful insights into Omani traditions, superstitions, and beliefs (“the newborn’s … fingernails which were not allowed to be clipped lest she becomes a thief in her future life”).

There is so much that this book can do to educate us and allow us to enjoy Arab literature. It is not a perfect novel, however. Celestial Bodies can be disjointed at times and lacks character depth. Character growth is seen, for sure, but it passes us by too quickly.

The book should be longer, given time to breathe, given more cohesive narrative threads. But in spite of all that, it’s a book that massively succeeds in hammering at your heart, making it beat faster, and asking it to love better.

(A final personal note: With regards to this book winning the Man Booker International Prize 2019, I’m glad that it did, for all it will do for Arab literature – especially women’s voices within Arab literature. However, it wasn’t my favourite to win from the shortlist; that would have been Drive Your Plow by last year’s winner, Olga Tokarczuk.

But my two favourites to win didn’t even make the shortlist: Swedish novel The Faculty of Dreams and the incredible Arabic short story collection Jokes for the Gunmen. So make sure you read these as well; they’re wonderful books.)