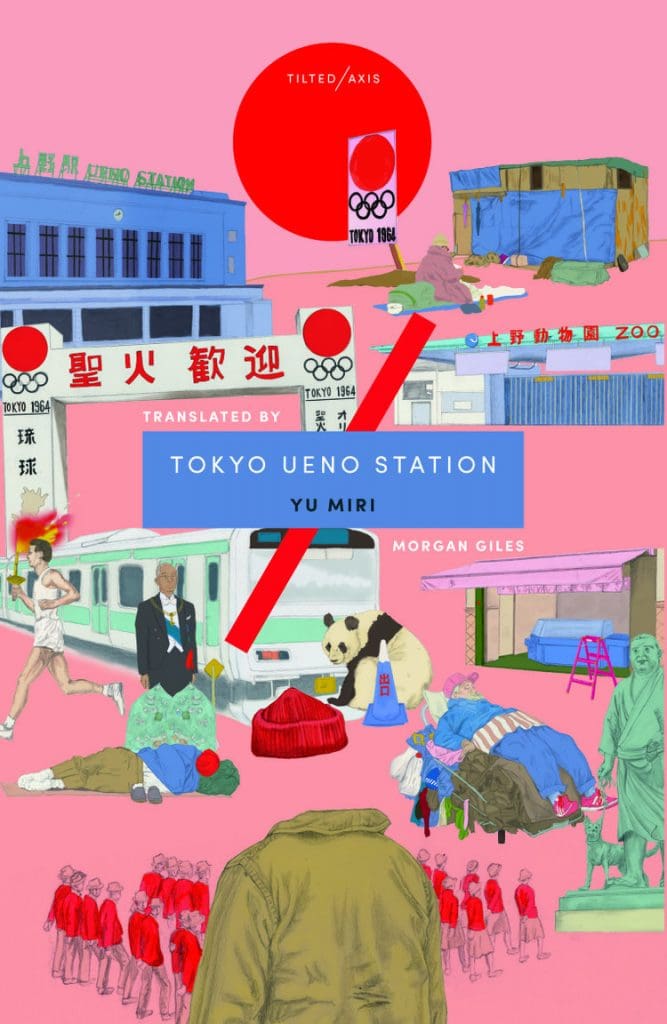

Translated from the Japanese by Morgan Giles

Here is a Japanese novel about social outcasts and the struggling and underappreciated working class, written by a social outcast, and translated by a proud socialist. Tokyo Ueno Station provides a harsh and honest look at the ways in which twentieth-century Japan has treated its people.

Yu Miri was born in Japan to Korean parents, and as such is a South Korean citizen and occasional recipient of racist bias and abuse in Japan. Despite this, she has had a phenomenally successful career in Japan as both a playwright and a writer of prose.

Although born in Yokohama, Japan’s second largest city, she now lives in a small town in Fukushima, close to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant which suffered a meltdown following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami which claimed thousands of lives.

Yu’s move to the affected area, and subsequent opening of a bookstore and theatre there, have aided in the promotion of the area which Japan’s government has reportedly come under fire for ignoring and all but abandoning for the sake of preserving its national and international image.

All of this is important to know before going into Tokyo Ueno Station, knowing that Japan is a nation that is remarkably good at advertising itself as a paradise to the West, but that many of its people are angry and have suffered greatly at the hands of its government, and those of mother nature.

The Disenfranchised

Kazu, the novel’s protagonist, was born in the same year as Japan’s emperor, and both men’s sons were born on the same day. While the emperor was born into the height of privilege, Kazu was born in rural Fukushima, a place that would later be ravaged by destruction in 2011.

While the emperor’s son would go on to lead a healthy life, Kazu’s son’s would be cut short, and Kazu himself would live out his final days as one of the many homeless barely surviving in a village of tents in Ueno Park. The narrative of this exceptional novel tells the life of Kazu after death; his ghost haunts Ueno Park and often quietly observes the movements and conversations of strangers passing by.

“I did not live with intent, I only lived.

But that’s over.”

These overheard conversations work as distractions which lead Kazu into, and then bring him back out of, flashbacks and memories of his wife, his son and daughter, and key events in his own life which are frequently tied to Ueno Station and the park. Kazu is a wildly sympathetic man, toeing the line between being admirable and pathetic as he recalls the worst moments of his life and those close to him.

Through his memories we become quickly and intimately familiar with people like Shige, a man who Kazu comes to know well in the homeless village – a kind man who adopts a stray cat and who Kazu posits might have been a teacher or a professor before his life took a bad turn.

Kazu himself is the embodiment of the working class who built modern Japan following the tumultuous end of WWII. He is a salt of the earth man who has sacrificed ever truly knowing his own wife and children for the sake of helping to build a modern Japan which has shown its thanks by rendering him homeless in his old age.

“Raindrops suddenly began to fall, wetting the rooftops of the huts. They fall regularly, like the weight of life or the weight of time.”

The novel’s structure narrowly avoids the straight and narrow, often flitting between the present day and Kazu’s daydreams of the past, some of which are short flashes and others are extended, heart-rending scenes told with real anguish and demanding of deep sympathy.

Kazu’s life is a string of tragedies which we must discover, and which ask us to consider what exactly is just and fair in our modern world. The first-person narration often feels like a ghostly hand gripping tight our own, pulling us through twentieth-century Japan, and asking us: is this fair?

Read More: Reviews of Tilted Axis 2019 novels: Every Fire You Tend and Of Strangers and Bees

The Outcast

There is a request asked of many these days who enjoy a good film, book, or any piece of media, and that is to keep politics out of entertainment. These people naively assume that it’s even possible to remove politics from media, from fiction, when politics informs everything we are and everything we do.

Yu Miri certainly knows this, and she knows how to weave a fantastic tale that is socially and politically woke, but is also primarily a fantastically human tale of a life simply being lived. Her aggression towards the class system and the exploitation of the working class is clear and intense – so much so, in fact, that it may just draw angry tears from the eyes of those readers who really care and really connect.

Through her uncanny skill at forming and presenting her heroes, Yu ensures that the ones who care are all of us.

Yu takes her politics seriously, and she wants you to as well. There is a passivism that many in Japan are often accused of when it comes to the decisions and actions of its government, but Tokyo Ueno Station asks us to keep in mind that every decision made and action taken, inside and outside of a government, is part of a chain and that chain is attached to each one of us.

“Regardless of what I am now, I am haunted by this day, today, and I would have liked to exchange a glance with someone, even a sparrow.”

There was perhaps no translator better suited to the task of gifting this book to English readers than Morgan Giles, a proud socialist who has clearly sunk her heart and soul into translating this story.

Through her pacing, her tone, and her vocabulary it is clear that she understands the writer’s own heart and vision, and that she wanted to ensure that this ambitious and honest book is loved and appreciated by as many in English as in its native Japanese. As a first literary translation, a better job could not have been done by anyone. Through her translation skills, the life and story of Kazu and his family brought me to tears.

Read More: Read our interview with Morgan Giles

Conclusion

This is one of those rare skinny books that will be kept tucked into the jacket pockets of readers, kept close to their hearts, ready to be re-read on a rainy afternoon or a stroll through the park. It serves as a reminder that every human is just that: human.

It is a tragically honest heart-on-sleeve examination and declaration of the sorrows of modern capitalist life, and more than anything it is a wonderfully written, spectacularly translated piece of fiction, and already guaranteed to be one of the literary highlights of 2019.

If you like this review then you might enjoy our review of Convenience Store Woman or The Last Children of Tokyo.