Translated from the Korean by Janet Hong

More often than not, when a musician finishes an album, their first job is to figure out what order the tracks should be played in. There’s a craft to getting the flow of the album right; do you start with a bang, or a slow crawl? Is there a big finish or a fade-out? Messing this up can compromise a lot for the listener.

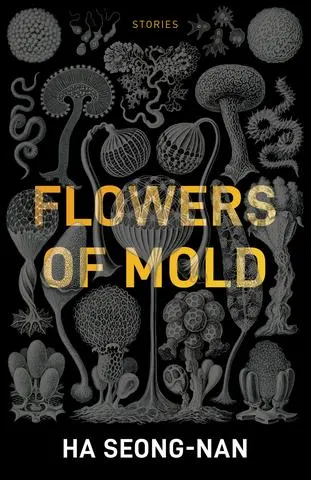

Flowers of Mold is a rare kind of short story collection which seems to have been compiled with these same questions in mind. It feels like a concept album, with a creeping intro that gently amps up the terror, increases the pressure and ends with what could honestly be described as a medley.

There are many approaches to horror. Stephen King himself described three types: the gross-out, horror, and terror. Terror is the most subtle of the three, the kind of fear that creeps up on you, disguised in perfectly ordinary clothes.

Korean author Hye-young Pyun is particularly masterful at this kind of fear. And now, Seong-nan Ha, has thrown her creepy hat in the English translation ring and delivered ten chilling stories about perfectly normal people that, nonetheless, manages to leave a little twinge of discomfort in every one of the reader’s muscles.

“When you enter middle school, you push aside thoughts of flying; you’re too old to play on the swings, and you’re no longer naïve enough to confess your desire to fly. You learn more about this gravity that keeps pulling you down.”

As I mentioned, Flowers of Mold flows like a concept album. It begins with a fade-in, with a story about a quiet young schoolgirl of below-average size. Written in the second person – a hard thing to get right – the story focusses on a nameless girl (as do many of these tales).

Struggling to learn gymnastics, she looks up to a senior girl to mimic her moves. When the senior girl has an accident, our protagonist feels herself begin to blossom, in size and skill. Immediately following this story is one with a similar tone: a young girl living on an orchard is ignored by her parents when she insists a man – perhaps one of the farmhands – has made his way into her room and assaulted her.

And so, it goes. The tales continue to build in tension as the violence becomes greater, or the people’s habits become more unusual, or their choices more baffling. The book itself seems to take on a life of its own, as it flourishes in its confidence. It makes greater and bolder noises. It groans and twists and shouts into the dark.

A Hand in the Dark

When reading short stories, you might be tempted to judge each tale by its title. I do. And when I turned the page and saw one titled The Woman Next Door, thoughts of the Tom Waits song What’s He Building chilled my thoughts and got me excited to read.

The story begins with an ordinary encounter and amps up its dreaded paranoia to such a degree as to have you gritting your teeth by its end. After moving in next door to our protagonist, a married mother, the new neighbour asks to borrow a spatula.

From there the two women become friends. Only our protagonist’s memory begins to play tricks on her, and the intentions of the woman next door become frustratingly unknowable and suspect. In twenty pages we feel ourselves begin to fall farther and faster into a pit of distress and obsession with truth and reality. It’s a tale that leaves scars.

“Above the stove hangs a spatula. The same one hangs above Myeonghui’s stove. I’ve named mine Myeonghui. I touch the spatula – the symbol of our friendship.”

Fear is one of the hardest things to nail in writing – especially in translation and in short fiction. It requires understanding the rhythms of writing; setting up just enough of a scenario to put that at risk or shift it around until it feels wrong.

It also means knowing people’s vulnerabilities, our paranoia, and or where our discomfort lies. Seong-nan Ha makes all of this look easy. For her, knowing the peculiarities of ordinary people is simple. She has the key. She probably forged it herself through painstaking observation, study, and hard work, but she has it.

And, as I said, to carry something as fragile as terror across languages is no small feat. Janet Hong recently translated Bad Friends – one of the most hard-hitting graphic novels I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading.

To see her tackle these short and creepy tales (which she translated eighteen years ago!) with so much subtlety, instilling the English text with unease and strangeness, makes my heart soar. She is a powerful talent in the world of translation.

Conclusion

To say too much about these stories, to analyse and study them, is to lose something. It’s better to sit quiet and let them wash over you.

They’re odd, and they know you. If you open yourself up to them, let them worm their way down your spine, you may struggle to sleep and you may find yourself turning your head twice as you walk down a lonely corridor, but it’s all worth it to experience tales of this gravity.

Flowers of Mold is unhinged just enough to make an uncomfortable noise as it opens up and all its demons spill out. Here is, undoubtedly, one of the best translated short story collections of 2019.

If you like the sound of this then you’ll love The City of Ash and Red and The Hole by Hye-young Pyun or Apple and Knife by Intan Paramaditha.