The publishing world, wherever in the world you are, is still dominated by men: male writers, editors, and publishers. This is despite the fact that the majority of readers around the world are women, and that so much of the best writing has always come from women authors.

Today, the best Japanese novels are all penned by extraordinarily talented women. Japanese women writers represent the cream of the literary crop in Japan.

It’s difficult to see the full landscape of Japanese literature without having grown up in Japan and reading Japanese. Most of what I’m talking about pertains to Japanese literature in translation; in other words, what I’m able to get a hold of.

But within that scope of translated literature, it’s female Japanese authors who prove to be the writers that move and inspire and challenge me the most as a reader.

Inspirational Japanese Women Writers

The authors I’m about to discuss below represent not only some of the best Japanese authors of this and the last century, but also some of my favourite writers, full stop. These writers have created masterpiece after modern masterpiece and I am so grateful to each and every one of them. These are ten of the most outstanding Japanese women writers of the 20th and 21st centuries.

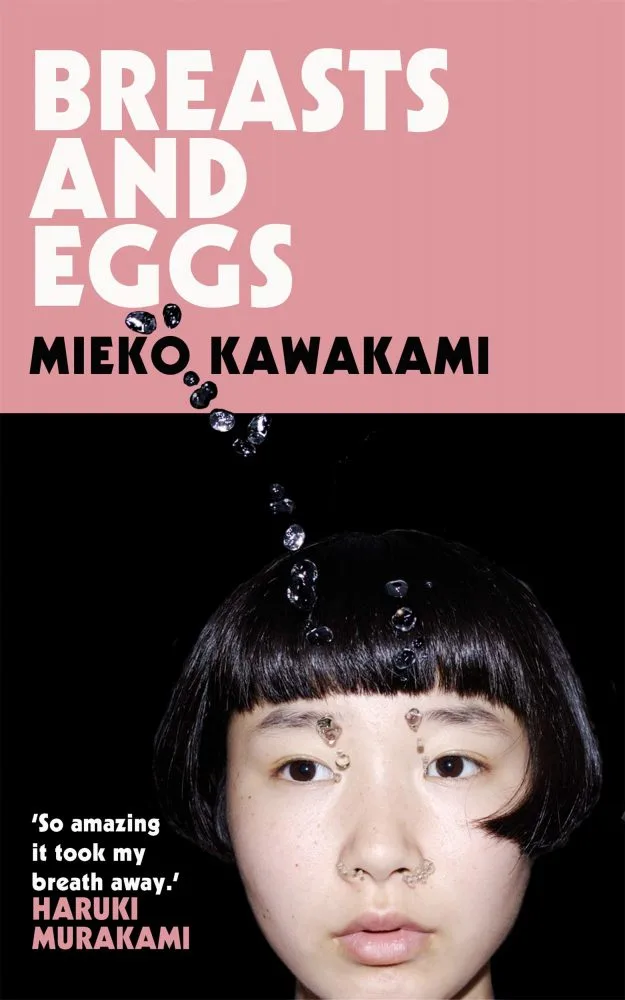

Mieko Kawakami

At the time of writing, Mieko Kawakami is the biggest name in Japanese literature in translation. A woman who grew up poor in Osaka and, now in her mid forties, has become one of the world’s literary stars. This is thanks to the ways in which she invites the reader to look at the world, and its women specifically.

In 2017, Pushkin Press published a translation (by Louise Heal Kawai) of Kawakami’s Ms Ice Sandwich, a sweet and heartwarming novella told from the perspective of a wide-eyed boy who grows enamoured with a young woman working at his local convenience store. He admires Ms Ice Sandwich for her punk and individualistic way of living and appearing on the world’s stage.

In 2020, Mieko Kawakami’s magnum opus, Breasts and Eggs, reached anglophone shores (via a translation by Sam Bett and David Boyd). Breasts and Eggs was originally a novella, followed up by a longer sequel. The English translation encompasses both books and is an unparalleled work of feminist power and scale.

Breasts and Eggs takes three women, all related but vastly different in how they see themselves and how they define womanhood, and tells their stories. Breasts and Eggs is a modern feminist masterpiece unlike anything else. It will cement Mieko Kawakami as one of the greatest female Japanese authors of all time, and cement itself as one of the great Japanese novels.

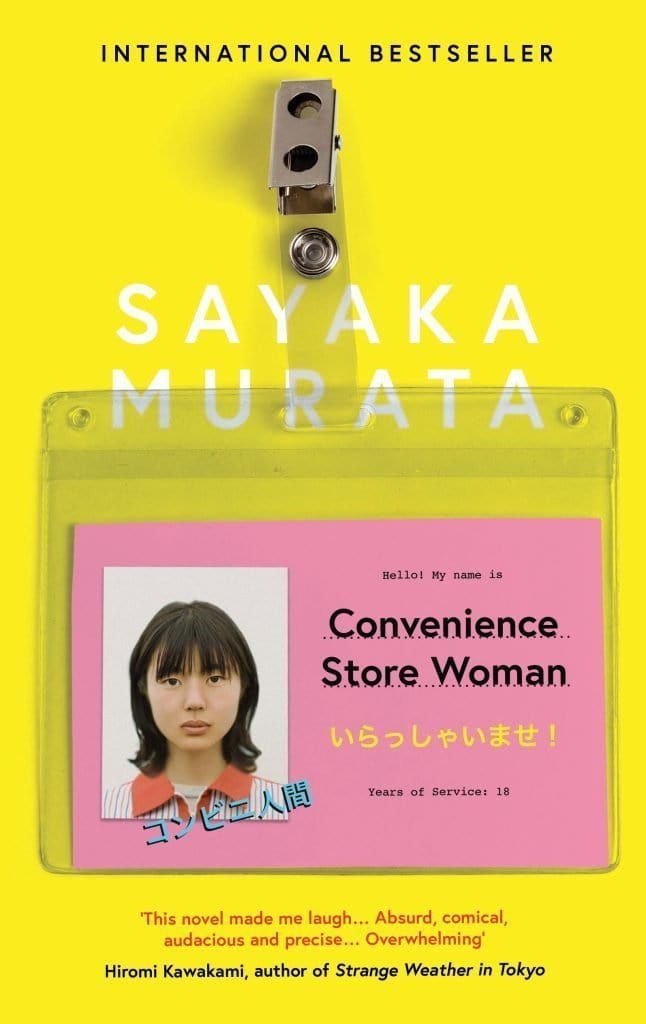

Sayaka Murata

I have so much love for the stories and novels of Sayaka Murata. Not a single author on Earth sees, thinks, or writes like she does. Murata spent the bulk of her adult life working in a Tokyo convenience store, and eventually turned that life into a novel.

Convenience Store Woman (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori and published by Granta in 2018) does a lot with a little. It’s a book which tackles enormous themes of individuality, happiness, satisfaction, capitalism, wealth, womanhood, feminism, responsibility, and more.

It is a book of infinite depth that should be considered and reconsidered again and again. It can influence your own place in the world and how you see it. I am so grateful to this book for so many reasons. Two years later, Murata has brought us Earthlings (also translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori and published by Granta).

This is a far darker and more surreal tale than Convenience Store Woman, but it is the one to show the strength of Murata’s imagination and the importance of her perspective on the world.

Earthlings is a feminist and humanist book that illuminates themes of control and power through distressing and frightening means. There exists nothing like it in the world of literature, and it shows us why we need minds like Murata’s.

Kikuko Tsumura

In Japan, Kikuko Tsumura is an author infamous for her approach to work culture, itself an infamous aspect of modern Japan. Born in Osaka, Tsumura quit her first job before having worked there for even a year. Fed up immediately by the toxic work culture of today, Tsumura turned her talents to writing engaging, warm, and funny stories about work and our relationships to it.

There’s No Such Thing as an Easy Job is Kikuko Tsumura’s first novel in English translation. Translated by Polly Barton, this book is separated into five chapters, each one a new job for its protagonist to try. After having burned herself out in a previous job, our protagonist is now looking for that elusive easy, stress-free job. Each one she tries, however, offers her something surprising, and shifts her philosophy every so slightly.

It’s a thoughtful book, full of humour and witty observations, along with some truly strange and intriguing jobs. There’s No Such Thing as an Easy Job is enough of a success to cement Kikuko Tsumura as one of the best Japanese women writers of today.

Yoko Ogawa

Few Japanese authors have made an impact as grand as Yoko Ogawa’s. This is a rather dizzying statement when you consider that more than thirty of her novels remain untranslated into English. Despite having only five novels out in English, her impact remains astonishing and the world of literature is a far more exciting place for the existence of her works.

Ogawa’s latest work in translation, The Memory Police (translated by Stephen Snyder), was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2020.

It tells the story of a Japanese island on which things eventually vanish, and the memory of those things is policed by the enigmatic titular Memory Police. It’s a dystopian novel that can be read from multiple perspectives, and can teach lessons as well as warnings.

While many of Ogawa’s works are considered dark and disturbing, her short novel The Housekeeper and the Professor (also translated by Stephen Snyder) is a heartwarming tale of love, friendship, and perseverance.

The Housekeeper and the Professor tells the story of a genius mathematician whose memory resets every eighty minutes. His new housekeeper grows to love and respect him, and shows companionship in the face of difficulty and loneliness.

Ogawa’s books often consider the importance of human perspective and the bonds we share. They deal with memory and the importance we place on it. She remains one of the most important Japanese authors working today and is, perhaps, the most legendary of Japanese women writers.

Natsuo Kirino

Here’s an author who is now considered one of the classic writers of 20th century Japan. Natsuo Kirino writers stories fuelled by her own feminist anger, and each one is full of fire.

Her novels Out, Grotesque, and Real World all centre around murder, all feature mysteries and suspense, and are all focussed on broadening perspectives on womanhood, and the actions and responsibilities of women, whatever their age, job, or background.

In Out, the most celebrated of these three novels (translated by Stephen Snyder), four women work at a bento box factory in Tokyo. Each one has a strained and exhausting home life. Eventually, one of them (Yayoi) takes a belt to her cheating and gambling husband’s throat and murders him while their children sleep.

For the rest of Out, our four protagonists work together to cover up the murder and remove any trace that might lead back to Yayoi. They are bound by the fact that all they have is each other. They live in a world of unfaithful, abusive men; of loan sharks and yakuza. Out is a feminist noir masterpiece; bleak and captivating.

Kirino is also the author of The Goddess Chronicle, a mythological novel about two sisters who live on an island, destined to follow very different paths. One is fated to be the island’s next Oracle, while the other will be banished. Once again, this is a novel about women taking fate into their own hands and doing what they can to cast aside the hand that they are dealt.

Hiromi Kawakami

I have a deep, personal love for Hiromi Kawakami. She was one of the first Japanese authors in translation I ever read, and her novel Strange Weather in Tokyo remains a favourite book of mine to this day.

Kawakami is an author whose writing is often full of hope and love. Her novels are grounded on the streets of Tokyo and feature the love lives of modern women and men.

Her book The Ten Loves of Nishino (translated by Allison Markin Powell), tells ten unique stories from ten women, all centred around one man and how his relationship with them changed or influenced their lives – for better or worse. It’s a creative novel that highlights the impact each of us can have.

In Strange Weather in Tokyo (also translated by Allison Markin Powell), her protagonists are a thirty-something salarywoman named Tsukiko and her childhood teacher (known only as sensei), who forge a unique and challenging — but ultimately rewarding — love affair. The novel uses these protagonists to explore the relationship between pre- and post-war Tokyo.

Her newest book, People From My Neighbourhood (translated by Ted Goossen), is a slender collection of micro stories, all bound together by the one surreal neighbourhood they’re all set in. These are creative, laugh-out-loud stories of strangeness and paranoia; impossible people living ordinary but impossible lives.

Yuko Tsushima

Unfortunately, Yuko Tsushima is no longer with us. When she passed away in 2016, Tsushima left behind an impressive legacy of great works, many of which were translated into English. When Japanese literature in translation grew in popularity after World War II, Tsushima was the only woman to gain notoriety and praise alongside male giants like Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, and Junichiro Tanizaki.

Sush was the power of her writing (though one shouldn’t ignore the obvious and deep-seated sexism within the publishing and translation industries).

Tsushima’s most famous novel in translation is Territory of Light, a book many modern readers are currently rediscovering. It is a beautifully written, elegantly translated (by Geraldine Harcourt) short novel about a woman’s rediscovering of herself and her surroundings after she leaves her husband and takes her two-year-old with her. They are now alone and free, and we see all the freedoms and fears that come bundled with this.

Hiroko Oyamada

A very new voice in the world of Japanese literature in translation, Hiroko Oyamada is already making big splashes with her first novel (translated into English by David Boyd): The Factory.

Thanks to The Factory (and her upcoming book in translation The Hole), Oyamada should soon be known as a successor to the legacy of Franz Kafka. With Kafka being one of my favourite writers, I was itching to read The Factory when it was first translated, and it did not disappoint.

The Factory follows three protagonists who all work in the titular factory: a labyrinthine, impossibly large complex in Japan. With the factory being allegorical of the inescapable, consuming, spreading mass of capitalistic, corporate life that is slowly engulfing us all, it’s easy to see where the Kafkaesque comes in. With only The Factory to go by so far, it’s amazing how plainly obvious Oyamada’s inevitable rise to greatness will be.

Banana Yoshimoto

Easily one of Japan’s most popular literary voices, Banana Yoshimoto is an absolute treasure of a writer. Speaking as a colossal fan of her works, it frustrates me that some writers often roll their eyes at the mention of her name, purely due to her popularity (much like how many of us do with Haruki Murakami’s works). Yoshimoto is a writer of intense heart and deep philosophical fervour who is as treasured as she is for a reason.

I first discovered Banana Yoshimoto – as many readers do – through her popular 1989 novel Kitchen (translated splendidly by Megan Backus). Kitchen is a novel about the fleeting nature of life, about death and how it overshadows us, and about the love we should have for one another while we’re alive.

Yoshimoto has a way of tackling familiar themes with incredible deftness and a deeper consideration than most writers. In Kitchen, Yoshimoto explores familial and romantic love in a hugely affecting way, and features a trans character at a time when good trans representation in media was almost nonexistent.

In her novel Goodbye Tsugumi (translated by Michael Emmerich), Yoshimoto explores the concept of sisterly love between two cousins, one of whom is sick and fragile, and has developed a spiky personality in order to protect herself.

These characters are far removed from those seen in Kitchen, but this variety of character, plus the maintaining of “the strength of love” as a theme, demonstrates the fierce intellect and artistic power of Banana Yoshimoto.

Yukiko Motoya

One a radio host and later a playwright, poet, and novelist, Yukiko Motoya is a creative powerhouse in Japan. In English, all we have right now is her fantastic short story collection Picnic in the Storm (or The Lonesome Bodybuilder), translated by Asa Yoneda.

Picnic in the Storm is a witty, funny, dark, surreal, and angry collection of feminist short stories born from a mind of bottomless imagination. These stories use surreal and impossible concepts to poke and prod at specific issues within our patriarchal world to an intensely savvy degree.

I hope and pray that we get more stories from Yukiko Motoya in English soon. The world needs more of her wit, charm, and anger.

Yoko Tawada

Based in Berlin and writing in both Japanese and German, Yoko Tawada is a fiercely imaginative and bold writer of huge concepts which range immensely from one another. She has won a laundry list of prizes both in Japan and in Germany, and her books are as touching as they are clever.

Tawada’s biggest books currently in translation are Memoirs of a Polar Bear and The Last Children of Tokyo (or The Emissary). The first is a trilogy of tales told from the perspectives of three generations of polar bear, each one living a very different life from the other two. It’s a book which considers identity and belonging from a very unique perspective.

The Last Children of Tokyo is a dystopian novel of grand themes and ideas. It tells the story of a retired author and his born-sickly grandson, living together in a quiet, polluted future Tokyo. This is a novel which shows us a possible future for our great metropolises once the oceans have risen and the air darkened completely.

Through her fiction, Tawada asks us to take a look around at the state of our world and start acting on thoughts like “what can I do about all this?”