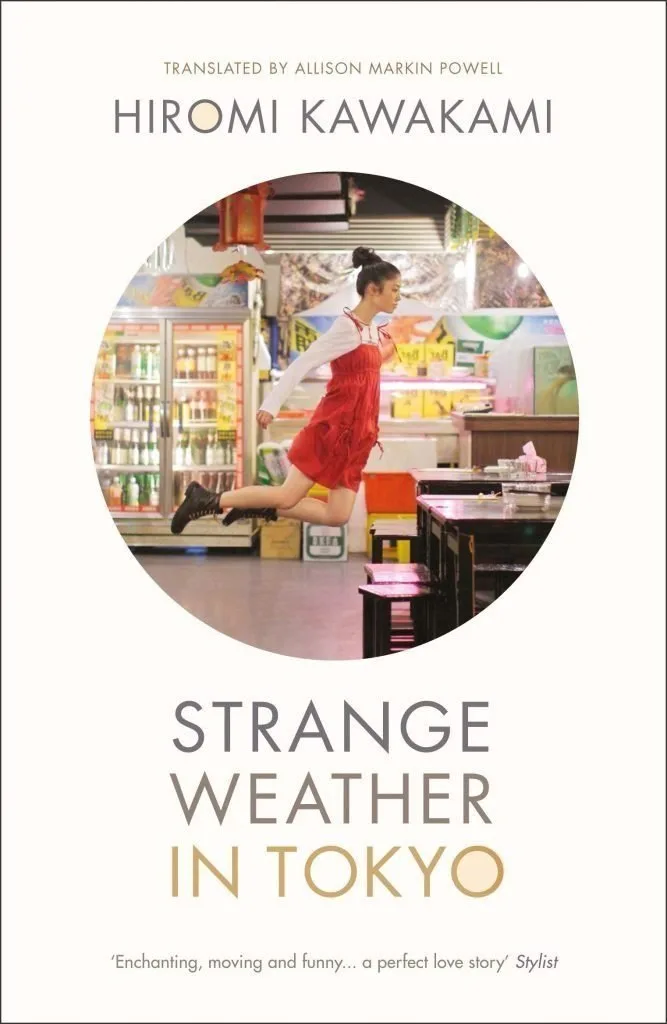

Strange Weather in Tokyo is a cultural examination of post-war Japan packaged into a touching, life-affirming love story for the ages. The twentieth century, and the end of World War II, saw a global shift in culture, technology, and economics never before experienced.

One of the places hit hardest by this was Japan, which previously had one of the most vibrant and fascinating ancient cultures, brimming with ancient customs which speak louder than laws, and art forms such as kabuki, calligraphy, and tea ceremonies.

All of this fell apart to make way for a culture now globally defined by cutting-edge technology, long working hours, swathes of businessmen in black suits, and a colourful youth culture of video games and anime. The blurb gives us a wonderful idea of the story and hints at the untraditional course these two characters will take as they slowly fall in love.

“Tsukiko is in her late 30s and living alone when, one night, she happens to meet one of her former high school teachers, ‘Sensei’, in a bar. He is at least thirty years her senior, retired and, she presumes, a widower.”

After this initial encounter, the pair continue to meet occasionally to share food and drink sake, and as the seasons pass – from spring cherry blossom to autumnal mushrooms. Tsukiko and Sensei come to develop a hesitant intimacy which tilts awkwardly and poignantly into love.

Strange Weather in Tokyo is a clash of modern and classic Japanese culture and customs, and of modern and weathered dating methods. The writing is clean, to the point, and surprisingly fast-paced. There are some real memorable points of this novel that make for a completely engrossing narrative.

Tsukiko is entirely relatable. She struggles on with her feelings for Sensei even though she doubts him for most of the novel. She drives herself crazy in a way most people have experienced at least once. She’s a classic introvert and reflects upon her personality often and, as a result, the reader truly develops an intimacy with her; an intimacy rarely seen in fiction as short and well-paced as this.

Tsukiko has a darker side that many will relate to, although perhaps might not want to admit that they do; Tsukiko spends all of her out-of-work time drinking alone, leaning against, and almost sinking into, the bar of her favourite pub. It’s a habit many of us fall in to.

“I felt a sudden rush of warmth in my body, and felt the tears well up once again. But I didn’t cry. It’s always better to drink than to cry.”

Her job is not touched upon, only her uneventful day-to-day existence. Tsukiko’s job is unimportant, and this in itself is a reflection of modern Japanese culture. ‘Who do you work for?’ we may ask, ‘a company,’ they will often simply say.

Again, this may sound dreary, but unrelatable it certainly is not. And that’s important. Here’s one example of how Tsukiko channels our very real fears and feelings of being out of place:

“I, on the other hand, still might not be considered a proper adult. I had been very grown-up in primary school. But as I continued through secondary school, I, in fact, became less grown-up. And then as the years passed, I turned into quite a childlike person. I suppose I just wasn’t able to ally myself with time.”

And this is a quote that every introverted individual will find themselves nodding along to with fervour:

“Forcing myself to make conversation felt like standing on a cliff, peering over the edge, about to tumble down headfirst.”

The humour of this novel is on point. More than once I found myself snorting out loud in a number of inappropriate places while reading this novel. The humour is genuinely dry, sarcastic, and just the right style to really get me giggling.

I’ve rarely experienced this while reading which speaks volumes about this wonderful book. One particularly memorable and hilarious moment is a fight between the protagonist and Sensei over baseball. I won’t spoil it here; you’ll know it when you read it.

I’d say over a quarter of the book consists of lavish descriptions of food and drink. This is not a bad thing. It’s done so well that you’ll spend most of the book hungry for Japanese food. Again, this is a minor but vital and appreciated insight into not only Japanese culture, but that of East Asia as a whole.

This focus on food in the book is perhaps Kawakami’s way of presenting a bridge between the old customs of Sensei and the new world that Tsukiko occupies, demonstrating that not all is lost in translation between the old world and the new.

On a greater scale, there is hope for a relationship between these two people and the worlds they occupy. Overall, this is one of the most delightful books I’ve read and I’d urge anyone who wants something lighthearted, but entirely beautiful, to read it. It’s a snapshot of another culture, of the struggle between the old and the new and of people who can’t comfortably fit into either.

If you like this you’ll probably like Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto and Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata.

Read our review of Kawakami’s new pseudo-sequel to Strange Weather in Tokyo: Parade and her new hit novel Ten Loves of Nishino.