Dystopian novels are seeing a massive resurgence in popularity right now, due to the state of the political world we find ourselves living in.

Novels written in the World War 2 era and during the Cold War have found relevance now more than ever before.

We’re all digging out our old copies of Nineteen Eighty-Four and The Handmaid’s Tale, and finding ourselves struck by how they seem more like ordinary life than dystopian fiction.

But the breadth of dystopian fiction goes way beyond Orwell, Huxley, Atwood, and Bradbury. There are authors from all across the globe (most notably East Asia) crafting their own takes on the dystopian novel.

The hypnotic thing about dystopian novels in translation, more than any other fiction in translation, is that these books are drawing from their own political histories.

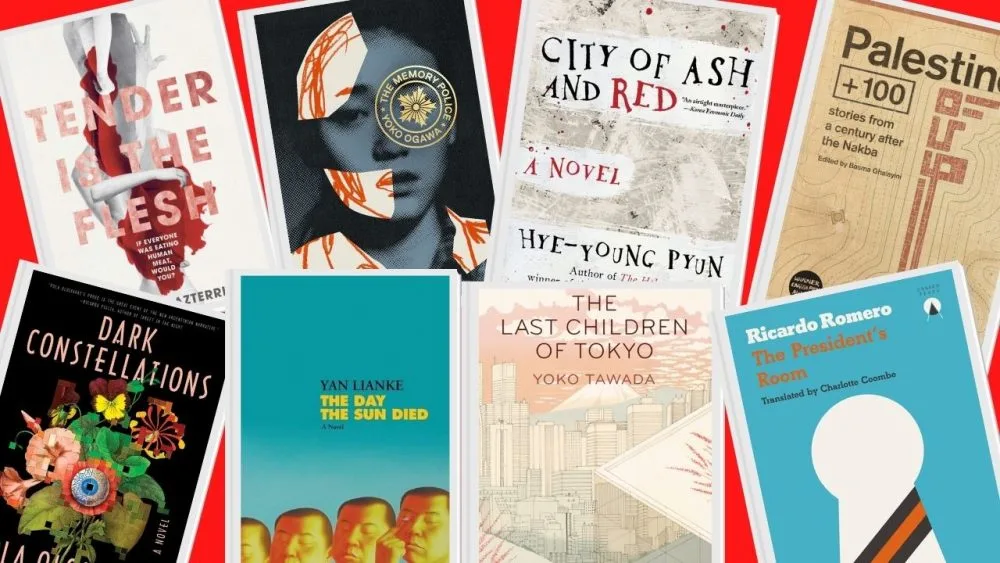

The Best Dystopian Novels in Translation to Read Now

Dystopian novels need to look at how their unique politics, religions, laws, and customs could be taken to extremes very different from the ones envisioned by Orwell and Huxley.

Translated literature is arguably at its most exciting and frightening within the genre of dystopian fiction. So, let’s take a look at eight of the best translated dystopian novels that are more relevant today than ever before.

Tender is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica

Translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses

Living in a world that is either a little to the future of, or a possible parallel to, our own, our protagonist Tejo works at a slaughterhouse which deals exclusively in human meat.

A disease is said to have tainted, and mostly wiped out, most non-human animals, and so came a period known as the Transition, wherein human meat production became an accepted norm across the world.

The humans that are bred for slaughter are not considered people, are referred to as ‘heads’, and are kept in much the same condition as cattle are today.

Therein lies the book’s first clear-cut message: to consider how modern-day battery farming, and meat and dairy production, treats non-human animals: the conditions they’re kept in; the ways they are raised, tortured, abused, and ultimately killed.

If this were the only message the book carried, it wouldn’t be adding anything new to the popular discourse. Fortunately, Tender is the Flesh offers a broader scope than that.

While Tender is the Flesh treads dangerously close to being gratuitous and unnecessarily violent at times, and its exposition never ceases to feel disconnected from the plot.

The questions and warnings it raises are ones genuinely worth sitting with and pondering on as our planet continues to diminish in a frightening multitude of ways.

Tejo’s personal story is also aggressively compelling, and it carries the book’s messages and morals expertly. It is, ultimately, those messages that make this book worth reading, and what makes it one of the best dystopian novels in translation.

Read our full review of Tender is the Flesh here!

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin

Penguin Ed. translated from the Russian by Clarence Brown

Often Orwell is cited as truly carving out the genre of dystopian fiction, but he was in fact inspired by Zamyatin’s incredible Russian novel, We.

Taking place a thousand years after the Russian Revolution, which Zamyatin had just lived through, trust in the system and the government is enforced by those known as The Benefactor and The Guardian, who liberally monitor ordinary citizens (sound familiar?).

Taking this one step further, everyone lives in a home made of glass. Anyone who attempts to rebel through art or creativity is lobotomised by the government. We is a truly chilling tale and the true origin to the genre of dystopian fiction.

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa

Translated from the Japanese by Stephen Snyder

This thrilling Japanese dystopian novel by The Housekeeper and the Professor author Yoko Ogawa tells the story of an island where everything is at danger of disappearing.

On any given day, something might disappear from existence – roses, perfume, ribbon, emeralds. And when they go, memories of them go, too. Those few people who can recall disappeared things are in danger of being abducted and killed by the mysterious and terrifying Memory Police.

This book wonderfully and engagingly comments on the importance of remembering our history so that we don’t repeat it. Our memories and our history are what guide our futures.

When they vanish, we become powerless. The Memory Police is pointing its finger at those nations whose governments control the media and what can be published, while also being a gripping and entertaining piece of translated literature.

Read our full review of The Memory Police

City of Ash and Red by Hye-Young Pyun

Translated from the Korean by Sora-Kim Russell

In this best of the Korean dystopian novels, City of Ash and Red, the protagonist is quickly and inexplicably transferred by his company to a country only referred to as C.

Upon arrival he finds the whole country drowning in disease and rubbish, with people being dragged into quarantine, and fear and distrust in the air.

Any fan of Kafka will recognise parallels between this tale and more than one of old Franz’s, with the key link being an overwhelming feeling of confusion, fear, and frustration.

Our protagonist seeks answers, but none are to be found. He wants to explain himself, but nobody will listen – nobody, in fact, cares.

Read our full review of City of Ash and Red

The Day The Sun Died by Yan Lianke

Translated from the Chinese by Carlos Rojas

In The Day the Sun Died, Li Niannian is a fourteen-year-old son of a funeral director living in a village in central China. One night there occurs a “great somnambulism” wherein all the villagers begin dreamwalking, returning to work or acting out their fantasies in the dead of night.

As seen from Li’s perspective, we the reader voyeuristically bear witness to the dreams-in-action of the individuals in the village. Darkly funny, darkly disturbing, Lianke writes with a hypnotic pace which maintains the tension that’s balanced on the edge of a knife.

Read our full review of The Day Sun Died

The Last Children of Tokyo by Yoko Tawada

Translated from the Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani

In The Last Children of Tokyo, Yoshiro and Mumei exist in a Japan in which the cities have mostly been abandoned, ties with the outside world have been cut, all other languages are no longer taught or spoken.

Many of the middle-aged people have moved to Okinawa, where they work on fruit farms which are almost completely the sole providers of food for the other islands of Japan. Tawada has, as all great dystopian writers must do, been true to her country.

She has taken a real look at the trends, habits, and laws which define Japan, and she has bent and twisted them; not so far as to distort them, but far enough to see where they might lead if left unchecked.

Read our full review of The Last Children of Tokyo

The President’s Room by Ricardo Romero

Translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Coombe

A delightfully eerie and Kafkaesque of dystopian novels, told by an unreliable narrator about a strange and uncanny place. In the suburb of a nameless town, every house has one room set aside for the president, if he comes to visit.

Nobody can enter except the president – that is, if he ever visits. Our narrator is a small boy who questions this normality, but even he can’t be trusted.

The President’s Room asks us to challenge the accepted norms when it comes to politics and our governments: the things expected of us, and the things we don’t question which, perhaps, we should.

It’s a Kafkaesque story taken to a more heavily political and radical extreme, and a fantastic example of the breadth of incredible literature coming out of Latin America right now.

Read More: 15 Romance Novels from Around the World

Palestine +100

Edited by Basma Ghalayini

Palestine +100 is a collection of science fiction stories set around 2048, one hundred years after the Nakba. Unsurprisingly, all of them are heavily political, and each in its own way. Dystopia aside, this is one of the best collections of Arabic short stories around.

The theme, subtext, and tone of each story is refreshingly individual, personal, and therefore refreshingly.

Though time and again there’s a Black Mirror parallel to be drawn, what with every writer using the broad and interpretive basis of sci-fi to paint an often bleak, sometimes eerie, occasionally funny, and always clever vision of the near future of Palestine.

(The publishers of Palestine +100, Comma Press, also published the equally impressive Iraq +100)

Dark Constellations by Pola Oloixarac

Translated from the Spanish by Roy Kesey

Dark Constellations is one of those rare visionary dystopian novels that takes the genre to new heights, ultimately exploring and questioning humanity’s insatiable hunger for knowledge and complete control.

It looks back at the 19th century golden age of scientific discovery, creates a time-bending science fiction tale which leads to a modern-day world of intense surveillance and control, as well as how science will ultimately advance the evolution of humanity itself.

A book that almost defies genre, blending dystopian themes with science fiction and dark fantasy. Here, you’ll find elements of Aldous Huxley, William Gibson, Haruki Murakami and George Orwell, all merging together to create something larger than the sum of its parts.

Dorohedoro by Q Hayashida

Translated from the Japanese by AltJapan

Dorohedoro is an oddity on this list of dystopian novels, mostly on account of it being a manga series, not a novel. But it is still dystopian and in translation, so I’m counting it.

Most importantly, Dorohedoro is also excellent. This dystopian manga is set in a far-flung future world divided in two. One place is a city called The Hole, and the other is a dimension filled with magic-wielding sorcerers who pop over to The Hole for some aggressive fun.

Sorcerers have been invading The Hole and experimenting on its citizens with magic, turning them into beastly things. Our protagonist, Caiman, is one of those experiments. Caiman has a lizard head and no memories of his pre-lizard life.

With his best friend Nikaido by his side, Caiman sets out on a revenge-fuelled mission to find the sorcerer who changed him. Along the way, bones will crunch and blood will spill.

The world of Dorohedoro is a lawless and gnarly one. The manga’s art drip-feeds remnants of Japanese society through its signage and architecture, but the dystopian world of Dorohedoro is a twisted and broken amalgamation of our own.

Further reading: The New York Times featured this engrossing story about how middle eastern authors are finding refuge in the dystopian novel.