Arab literature is a world that contains multitudes. From a Western perspective, you might expect Arab stories to provide you religious or political perspective on a world you know little about. Sometimes that’s true and sometimes it isn’t. While the Arab world is home to revered classic novels and modern works of brilliance, one of the best ways to get started with Arab literature is to read Arabic short stories in translation.

Short story collections from Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and beyond can give readers a taste of what to expect in the wide world of Arabic literature. So, if you’re looking to start reading more Arab literature, here are a few collections of Arabic short stories to get started with right now.

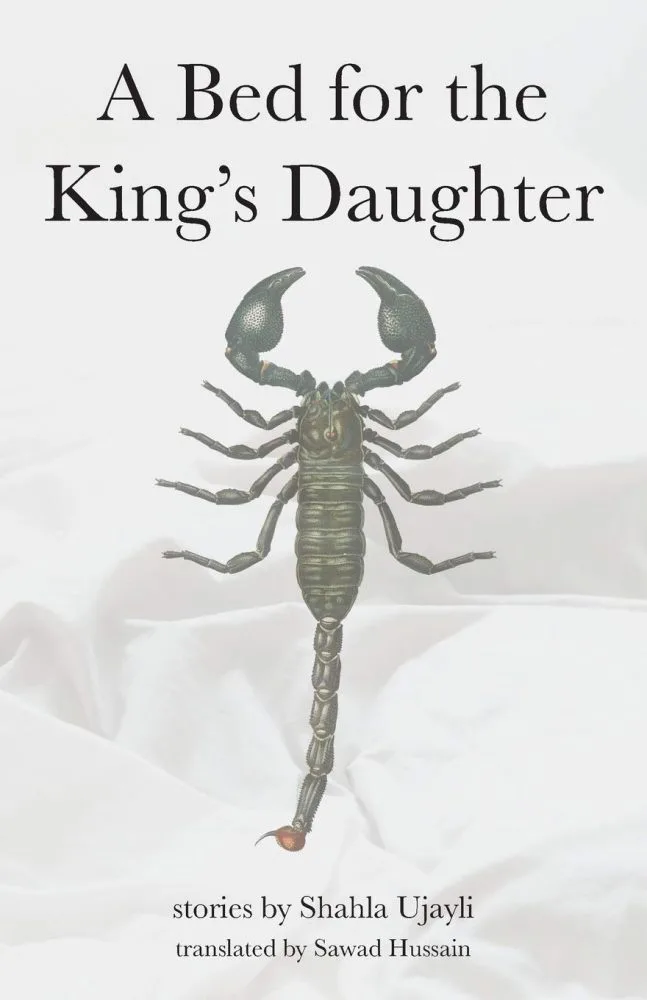

A Bed for the King’s Daughter by Shahla Ujayli

Translated by Sawad Hussain

In her translator’s notes for this fantastic collection of Arabic short stories, Sawad Hussain remarks:

“The sheen, shine and sparkle of this electric collection are found in the unsaid rather than the said, the unwritten rather than the written.

A Bed for the King’s Daughter is unlike other Arabic short-story collections, which are usually centered on a single aesthetic, or firmly rooted in a particular location or span of time.

While in these twenty two very short stories, there appears the occasional Arab name or reference; the stories are not exclusively situated in the Arab world — allowing their narratives to fly wherever they wish.”

Hussain’s words of analysis and praise continue on like this, energised with passion and personal investment, coupled with grounded consideration and intense admiration. And I agree with every word of praise she heaps on this book of Arabic short stories.

A Bed for the King’s Daughter is a disjointed, surreal, lawless, floating thing. It is a vessel for exploring and considering whatever Ujayli feels passionate, positive, or angry about.

The very first story, The Memoirs of Cinderella’s Slipper, takes the fairytale heroine and places her in a modern setting, with Cinderella heading to a corporate job interview. On the way, men do everything from judging and fearing to groping and attacking her. Each time she wields her slipper as a defensive weapon.

It’s a story about the everyday struggles of women; it travels an entire spectrum of attitudes that men often have towards women: entitlement, judgment, possession, fear. And it does all this with just a handful of pages, ending as soon as its message has been delivered. Not a word is wasted.

A later story, The Night the Building Collapsed, is a tiny tale that can be read in a single minute. It records the time spent by a handful of people living in a tower block: where they were or weren’t, what they were or weren’t doing when it came down.

This story is all the more impactful for its brevity and, as Hussain remarks in her introduction, it is made all the more powerful by what it doesn’t say. Though, naturally, what it does say also leaves an indelible mark on the reader.

The titular tale A Bed for the King’s Daughter is one of the most entertainingly imaginative tales in the collection. It tells two parallel stories at once: a Sleeping Beauty-esque fairy tale and a snippet of the modern life of a man obsessed with a woman journalist whom he is desperate to avoid for his own heart’s sake.

As the two stories advance, both with the moral of fate being inevitable, they both reach the same narrative conclusion and also find a way to meet in an unexpected and satisfying way.

A bed for the King’s Daughter is a playful, smart, warm, cold, harsh, beautiful collection of strange, surreal Arabic short stories. Some have clear morals and themes; some do not. All are inventive, strange, and exciting. This is a magical collection of Arab short stories.

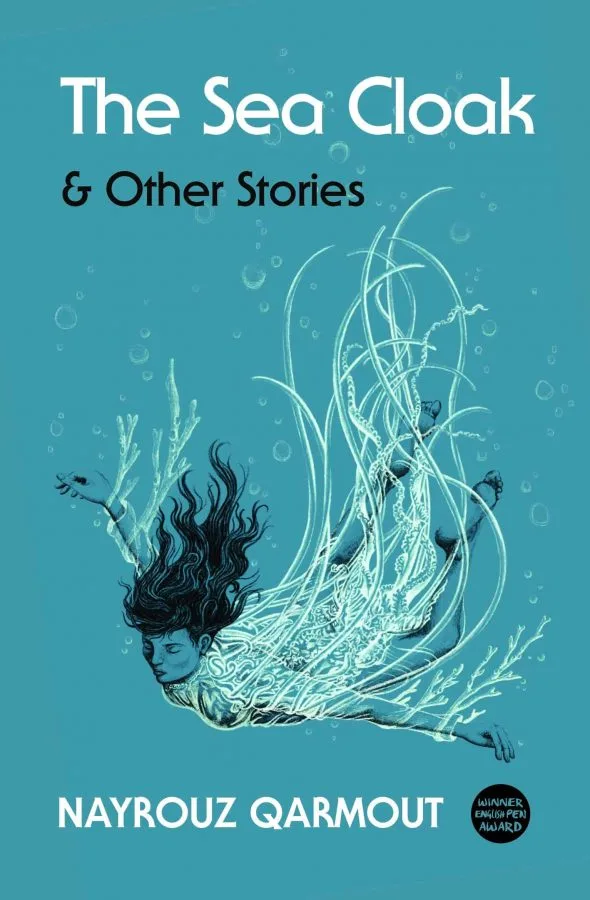

The Sea Cloak by Nayrouz Qarmout

Translated by Perween Richards

The ongoing unrest in Gaza, the state of divide between Israelis and Palestinians, is often reduced by those of us outside to ill-informed political debates at best, and total confusion and oblivious guessing games at worst. Those of us who sympathise with the plight of Palestinians discuss money changing hands, political agendas in the right-wing papers, and the vilifying of one versus cries of compassion for the other.

But even in showing our political sympathies, do we truly understand life on the ground for Palestinians? How ignorant is our caterwauling? What we often need as much as hard political facts and details is true connections to those innocents who suffer the most. We debate these topics while forgetting that they are people – not chess pieces.

Through The Sea Cloak — a collection of eleven biting and honest Arabic short stories — Nayrouz Qarmout offers that connection. She allows us to replace these pawns with people. She opens the door between us and Palestine, stretches out her hand and says, “Here, come see our lives for yourself.”

Qarmout herself, a feminist journalist and women’s rights campaigner based in Gaza, grew up in a Syrian refugee camp. She has experienced life for Palestinians in almost every way that it can be experienced.

As authorities on family, women’s rights, and childhoods in Gaza go, she is arguably the foremost. And here, in The Sea Cloak, she channels her knowledge, her emotional experiences, and her insights into a collection of human stories that are, while undeniably political, more concerned with family life and childhood.

Though of course, these being the lives of Palestinians, family life and childhood are inextricably tied up in politics. My favourite story, Pen and Notebook, tells the story of a group of three brothers: small, medium, and large. The eldest brother drives the other two, in their school uniforms, across town in a donkey cart.

Pedestrians, drivers, and even police chastise them for their unsafe mode of transport before they arrive at a landscape of rubble. They spend the morning piling rocks from the rubble into the donkey cart, a different sized pile for each boy.

Their labour is described in detail: rhythmic and logical, but also playful and impassioned. Finally, after a full day has passed, they take their collected stones to a merchant and exchange their work for payment. At home, their father is sick, and their mother greets them all with a warm hug.

The eldest boy gives her most of the money they made, and hands the remaining coins to his younger brothers, commanding them to use it to by a notebook and pen so they might learn to write.

I could continue recounting all of these Arabic short stories in this same way, from the woman who recounts her furious feminist childhood rows with her misogynistic maths teacher in The Long Braid, to A Samarkand Moon: the story of a dangerous road trip taken by a young couple who were once innocent in love but have since grown apart in their politics and their morals.

These tales are rich in debate. They reveal to us the complex nature of belief and tradition in Islam that is often overlooked by those of us outside of the faith. The Sea Cloak might be stories, but they are stories that bring us far closer to the real lives of Palestinians than ever a news report or a collection of data could.

Beyond that, they are a full exploration of the emotional spectrum, with the ability to draw tears and laughs from us; the two actions being separated perhaps by a single page. Qarmout has a raw gift for empathy and translator Perween Richards is able to capture every nuance and detail of Qarmout’s themes, ensuring that nothing is lost, and everything is gained.

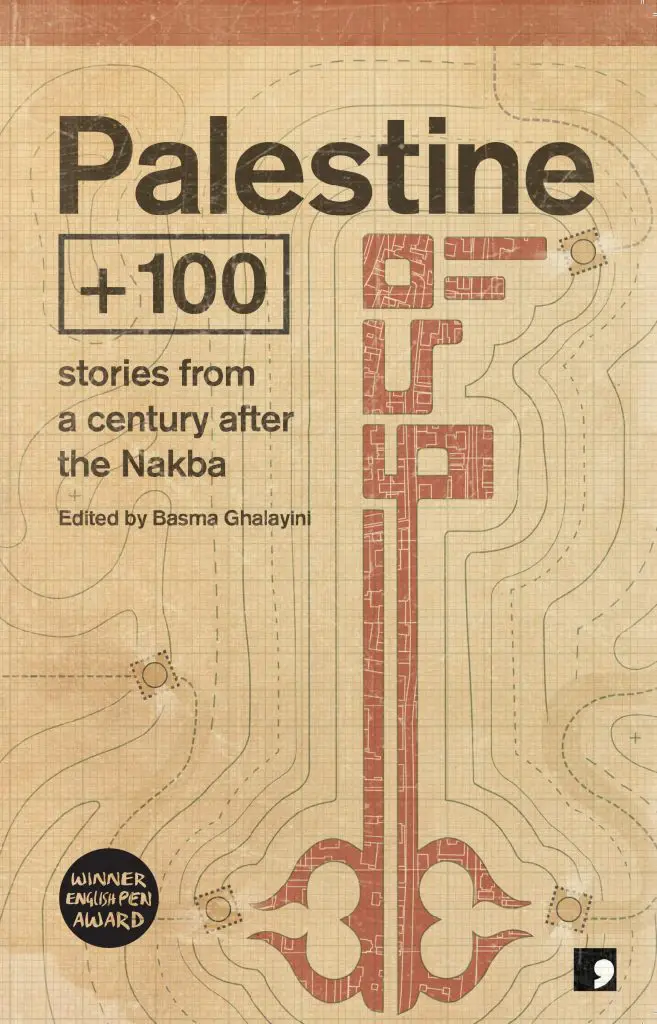

Palestine +100

Edited by Basma Ghalayini

To this day, the divide between the States of Israel and Palestine is a topic ferociously debated by politicians and civilians across the globe, and is the source of the misery, fear, and rage felt by every Palestinian every day. Often left voiceless in this divide, twelve incredible Palestinian writers have here, in Palestine +100, been given the chance to shout loud and clear and have their stories accessible across the world with the help of Comma Press.

Palestine +100 is a collection of Arabic short stories — more specifically, science fiction stories set around 2048, one hundred years after the Nakba. Unsurprisingly, all of them are heavily political, and each in its own way. The theme, subtext, and tone of each story is refreshingly individual, personal, and therefore refreshing.

Though time and again there’s a Black Mirror parallel to be drawn, what with every writer using the broad and interpretive basis of sci-fi to paint an often bleak, sometimes eerie, occasionally funny, and always clever vision of the near future of Palestine. To call these pieces of creative sci-fi predictions might be to mislabel them. Some, after all, might be seen as fantasies; others, warnings. Some are positive, and some are not.

There’s an enormous breadth of vision to be enjoyed in Palestine +100, and that speaks to both the fire burning inside each writer, as well as the infinite ways in which the genre of sci-fi can be moulded in order to serve whatever vision of the future the author wants to craft.

The book opens with an absolute gut-punch of a story titled Song of the Birds by Saleem Haddad. It’s a deliciously creepy blend of horror and science fiction which plays distressingly with the themes of PTSD, loss, family bonds, and even the age-old philosophical question of ‘how can I know what is real?’ or ‘how do I know I’m awake?’

It’s a story which, aside from the established transgender allegory, also inspired The Matrix. And there are unavoidable parallels to be drawn between that film and this story. But this story builds to its Matrix twist in a far more impactful, grounded, surreal, and upsetting way.

I can’t deny having tears stinging my eyes within the first few pages, as the story opens on the protagonist wading into the ocean, lamenting the loss of her brother to suicide, before having lucid visions of the water being full of trash and naval boats aiming their guns in her direction.

I would happily write an essay on the layered nature, the political message, the metaphors at play, and the emotional impact of this story alone. Palestine +100 will not bring justice for the Palestinian people. At least, not by itself, but it’s part of something vitally important: it serves as a reminder that they are still there, still fighting, still angry, lost, and full of burning.

The writers of Palestine are inspired, witty, perceptive, sharp, and drawing from a deep well of love, hate, indignation, and volition. All of that is on bright and beautiful display in this deeply impactful collection of Arabic short stories which are capable of drawing attention, support, and love for the people of Palestine.

It’s a call, a roar, a celebration of the artistic and literary power of Palestine. I love these stories, and I love their writers.

The Quarter by Naguib Mahfouz

Translated by Roger Allen

“The manuscript of these narratives was found in a drawer with a note attached stating, ‘To be published in 1994’.”

This is what Roger Allen, long-time translator of Nobel Prize-winning Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz, reveals in the introduction to The Quarter.

He goes on to say that this was the same year that Mahfouz was stabbed in the neck outside his home in Cairo, following a fatwa which was issued by a Muslim cleric after Mahfouz refused to condemn The Satanic Verses — the seminal work of Mahfouz’s contemporary Salman Rushdie — to be heretical.

The introduction to this recently-discovered short story collection does an immaculate job of familiarising us with the life, works, and politics of Naguib Mahfouz, and of framing these specific stories around his own life at the time that these stories should have been published.

These Arabic short stories themselves all take place, as the name suggests, in a single hara — or quarter — of Cairo. It’s an anonymous district bustling with eccentric people both good and bad. There are familiar faces and places that we grow to know well, and others who float past us in a handful of pages.

Transience, and the paradox of fluidity and tangibility, define this place, its stories, and its people. And even Allen himself remarks at the end of the introduction:

“Since these eighteen narratives show a distinct unity of location, purpose and style, are they a complete work or merely part of what was to be a larger project that was begun but never completed? It is perhaps only appropriate that we are left with a mystery. Meanwhile, we are without a doubt grateful for this unexpected gift.”

Only a man who had spent his literary career documenting through fiction the lives of Egyptian people on the ground would be confident enough to cast aside all of the rules that make the short story work as a medium, and instead provide us with eighteen narratives, often with no beginning and no end.

Narratives with an average length of five pages, which typically open with a statement of tragedy, scandal, or unrest. Narratives that leave us as quickly as they arrive, demonstrating both the ever-shifting face of a neighbourhood and the cyclical rhythm of motion: there is an issue, it causes a stir, some laugh, some cry, some win, some lose, the Head of the Quarter is approached, the problem is resolved. Or it isn’t.

That is the predictability, the beat of these narratives. Where they are compelling is in their content: the nature of the tragedy, and the actions of each individual. My own favourite story came early on in the collection and is titled Pursuit. It opens with a woman who left the quarter after discovering that she has become pregnant, and then returns with a new-born baby.

She then begins to sell sweets on the street outside a shop owned by the man who is the baby’s father. He refuses to have anything to do with her, complains about her to the sheikh, and begins to fall mad with anger and paranoia. The woman takes no charity and will not be moved, saying that she will “keep the baby where he can see it, so he’ll always remember his crime.”

This was my absolute favourite narrative in The Quarter. It demonstrates the strength of a woman scorned, the powerlessness of a leader to condemn a woman who has committed no crime, and the fragility of a man’s ego when he is faced with his own transgression.

There’s a kind of magic at play in this collection of Arabic short stories, where it’s easy to imagine that nothing exists beyond the bounds of this quarter. Whenever a member of the community is described as having run off or journeyed abroad, we imagine them vanishing into empty space, as though the quarter exists in a bubble with nothing beyond it.

It’s a perfect state, an absolute existence in its own right. And each person here we get to see in a fleeting moment commit a crime, give into some sin or other, or make a mistake that ripples out across the whole quarter. There’s an electric excitement to the lives of these people, as there is to the lives of all of us that’s plain to see when we stop and watch.

The Book of Cairo

Edited by Raph Cormack

There’s an absolute complexity to Cairo, as these Arabic short stories prove to us. Disparate religious groups; political ideologies ranging from the far left to the far right; corruption from the street level to the heights of government. It’s a city that may be impossible to ever know, but reading these tales is certainly a worthy start.

Every one of them is like a moment in time, but each moment has every chance of making you laugh – through unusual exchanges in everyday life – or cry – forcing you to look on helplessly as deep cruelties unfold.

Many of these Arabic short stories betray the power of words. Whether these words be lies and rumours spread about on the air with the intention of defaming and destroying someone, or words spoken in jest that carry a harsh weight that only grows heavier over time.

This obsession with words exposes the paranoia that exists in a country where corruption is thick, and the walls can talk. But there’s also a joviality to some of it, where we see the unique sense of humour of Arab men who laugh in the face of things many of us in the West don’t have the strength to face.

One story, written by Hend Ja’far titled The Soul at Rest is a first-person narrative about a man who works in the obituaries section of a newspaper.

When an Egyptian Christian visits, asking the narrator to publish the obit of a Muslim friend, this moment — and another which follows — emphasises the turbulent and violent aggression which exists between Muslims and Christians in Egypt, as well as the hypocrisies which exist within each religion (some Muslims behave more liberally, while others condemn those who do for acting in such a way).

It’s a complex topic that is boiled down with incredible force of pressure and will into a tiny tale. One which exists here as a pocket-sized and yet deeply layered example of the complexities of religious politics in Egypt. This story is like a haiku that uses three lines and fourteen syllables to say almost all that needs to be said about Egypt’s relationship with religion.

Though each of the ten Arabic short stories found in The Book of Cairo is unique – ten stories by ten writers, translated by ten translators – they feed into one another artfully, like a movie soundtrack, a concept album, or a full novel.

The cogs of Cairo turn through this book, and they move faster and more erratically as the pages turn — just as life in Cairo itself does. An appreciation grows through the reading of this book — appreciation for its people, its place on the global scale, and its ability to work as a culture that often seems like a Frankenstein’s monster of inharmonious pieces.

Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun

Translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

This collection of Arabic short stories by the author, journalist, and activist Rania Mamoun is one of the first ever translations of a Sudanese female author into English – calling into question just how much world literature exists out there, especially by women, that we in the Anglophone world have never had access to.

This translation trend that is bringing more and more lesser-known world literature into the spotlight is so exciting and must continue. Thirteen Months of Sunrise is a captivating collection of Arabic short stories that burst with vibrancy. Here is a colourful cast of characters that simply exist in their world – they do not begin or end; they merely are.

As a reader, you feel privileged to have shared a day, or maybe just a moment, with them, utterly convinced by the notion that they’re carrying on their daily life in Sudan long after you’ve closed the book. Mamoun plays with a variety of literary styles throughout and expertly blends scenes that are grounded in reality with surrealist episodes that never once feel out of place – reflecting the always off-kilter daily lives we all live.

Themes of colonialism, war, immigration, urban alienation, love, loss, and grief abound in these tales. Every story is a snapshot of something that makes life unique and special – not just life in Sudan but life as a citizen of Earth.

Sudan is one of the largest and most diverse states in Africa and Mamoun effortlessly paints a picture of the various communities and individuals that live together, often passing like ships in the night but inevitably sharing their commonalities while learning from one other.

Thirteen Months of Sunrise will have you witnessing everything from fleeting love, bonded by shared knowledge and culture, to death and those things left unsaid. Like these stories, life, and that of those around you, is fleeting and must be cherished.

Jokes for the Gunmen by Mazen Maarouf

Translated by Jonathan Wright

Jokes for the Gunmen is simultaneously the title of this collection of Arabic short stories, the title of its opening (and longest) story, and the theme of the entire collection. Having been born as the son of Palestinian refugees and grown up in a city and country torn apart by war and civil unrest, Mazen Maarouf is no stranger to suffering and what it can do to the human soul.

He also knows that, while at times it is important to demonstrate and decry the horrors and evils of war, it is also sometimes worth laughing in the face of it.

This stunning collection of short stories does both of those things in equal part, and with immeasurable impact, telling stories of people living at the edge of a warzone, people hiding from the enemy, and people trying to find things to laugh about in the face of tragedy.

Since leaving the teaching profession for poetry writing, Mazen Maarouf has had several books of poetry published and, after moving to Reykjavik, he has now produced his first collection of short stories. Jokes for the Gunmen is a collection of Arabic short stories which escapes simple description. Each tale is unique, but a thread weaves its way through every one: strangeness.

Some of the tales in this collection hit hard, and others leave the reader scratching her or his head. A few hit like an abrupt punchline. Whatever the tone, most stories are about war, some are about tragedy, and all are a little strange.

Through every story here, there is an element of the sudden and the unexpected. Matador, for example, tells a story from a young man’s perspective, of his uncle whose dream was always to be a matador, and so he wears a matador uniform every day to his job at a slaughterhouse.

As the story goes on, he dies three times. It’s a story which will leave you feeling confused, amused, and a good amount of pity. Likewise, Portion of Jam begins as a sweet tale of a father amusing his child and ends with a form of tragedy that hits with the kind of unsettling gravity that leaves you winded.

Mazen Maarouf knows your soul. He knows the souls of strangers, and how those souls interplay. He knows what you are capable of in your brightest and your darkest of moments.

He doesn’t underestimate or overestimate anyone. He also knows that life cannot be accurately explained and examined with simple methods, and that often we have to look at life through a prism which distorts and confuses us, in order to see the truth behind the ordinary.

To have this much empathy must be truly difficult, but if it leads to art of the calibre found in this book of Arabic short stories then we must be grateful.

Read More: 14 Middle Eastern Cookbooks (For Aromatic Home Cooking)