It seems as if Latin American literature has always been dominated by men, especially when it comes to translation: you get your Borges, Cortázar, Rulfo, García Márquez, Neruda, Bolaño, and so many more.

But Latin American women have always been there, writing fantastic fiction that has defied stereotypes and allowed them to imagine a different world.

I am thinking of Victoria Ocampo, the editor of Sur magazine and author, as well as her sister Silvina, an extraordinary short story writer.

I can also name my favourite Chilean writer, María Luisa Bombal, whose dark and atmospheric stories shaped so much of my reading taste growing up.

Even the first Nobel Laurate in Literature in Latin America was a Chilean poet, Gabriela Mistral, whose beautiful and honest poetry is still very inspiring.

In Mexico you get Rosario Castellanos, a poet who championed feminist causes, and we can even go further back to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a nun in Colonial Mexico who wrote passionately about women’s rights, love, and theology.

Must-Read Books by Latin American Women

This is a very long way of saying that women in Latin America have been writing for centuries, and they are great at it. But in the last couple of decades, books by women have started dominating the scene.

The International Booker has longlisted at least one Latin American woman every year since 2017 (with three being nominated in 2020!), which also speaks of the amount of work that is being translated, too.

(Fellow translators, ¡buen trabajo!)

I am here to boost some writers who haven’t been as well publicised, but that I think deserve a lot more publicity.

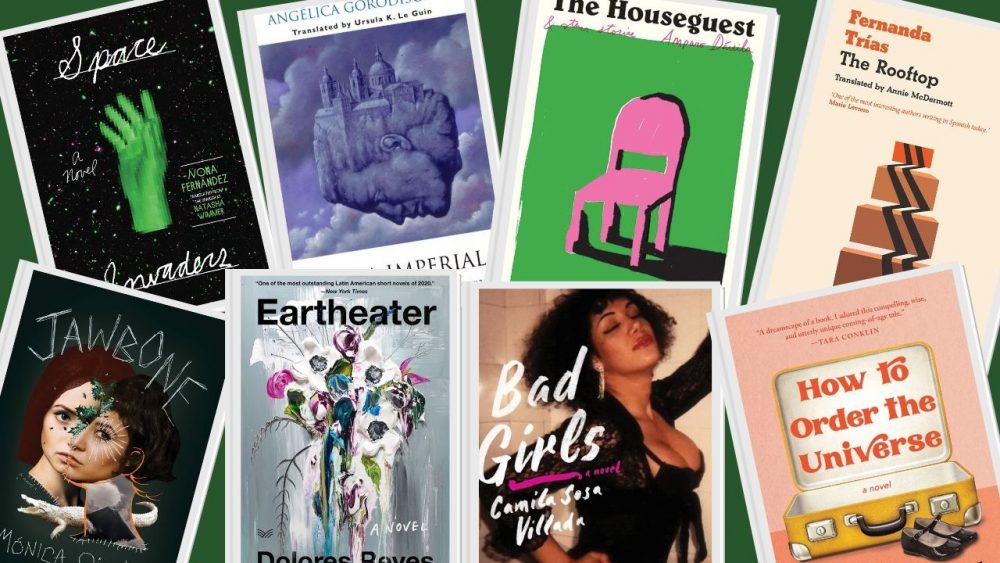

Space Invaders by Nona Fernández (Chile)

Translated by Natasha Wimmer

Nona Fernández is a powerhouse when it comes to contemporary Chilean literature: novels, short stories, essays, plays, and even screenplays for some teleseries. She has done it all.

Her novels are often centered around growing up under Pinochet’s regime, and Space Invaders is a particularly good example of how she presents this theme and how she attempts to explore the trauma of the dictatorship.

The narrators of this novel are a group of kids growing up in 1980’s Santiago, who are all trying to pin down their memories of one of their classmates, González, the daughter of a police officer who appears to be moving up the ranks.

She appears to be haunting her former classmates’ dreams, bringing the memories of school uniforms, childish letters, and computer games.

Politics start at the background, blurry in the wake of the end of childhood, but as the story progresses and memories become sharper, the horrors of the dictatorship appear clearer as well.

Childhood appears here as a bit a bubble when it comes to the harsher aspects of reality, and the violence inherent to the system pierces it in tragic and horrifying ways.It’s a very slim novel (fewer than 90 pages in the Spanish edition), so anything else I say could be a spoiler, so just go and read it.

The Rooftop by Fernanda Trías (Uruguay)

Translated by Annie McDermott

The Rooftop was originally published in 2001, but after 2020, this slim and intense piece seems to have reached a whole different meaning.

The claustrophobic feeling that permeates the novel captures the feeling of constant lockdowns and fear of what might be on the other side of our doors.

This is a book mired in paranoia. At the beginning, the pregnant narrator and her father have enclosed themselves in their apartment.

There’s a constant sense of fear and stress throughout the novel, as the main character’s fears appear to be confirmed.

The exterior world becomes frightful and menacing as her pregnancy draws to a close and the relationship with her father reveals itself to be darker than one might have thought.

It’s a very short and intense novel, which manages to create a sense of unease and terror by not saying a lot.

We only are aware of the narrator’s fear of the outside world, and we can only intuit what is that which she finds so terrifying. In a world in which the outside has become a bit of a mysterious and maybe dangerous possibility, this book hits on the anxiety of the closed space.

Our Dead World by Liliana Colanzi (Bolivia)

Translated by Jessica Sequeira

I’ve always enjoyed short stories collections, and I am very lucky that Latin America has some stellar short story writers right now.

Liliana Colanzi’s Our Dead World is one of them, a fascinating collection of dark and twisted stories.

On its pages, a group of kids attend the funeral of one of their classmates, a mysterious wave of suicides haunts a college campus, and a cannibal explores the streets of Paris.

The stories are all very different, but they all share a sort of dark humour, a hint of irony that appears to string them all together, across time and space, and even genre.

My favourite might be “Alfredito”, the story about a group of kids coming to terms with the death of their classmate.

She has a way of calling attention to the details and specificity of the situations she writes, grounding even the stories with the most fantastic elements and making them vivid and true.

If you’ve enjoyed Mariana Enríquez and Samanta Schweblin, this collection hits a similar spot: dark and imaginative, the heirs of writers such as Cortázar and Silvina Ocampo, who explore the creepiest corners of the world.

The Houseguest and Other Stories by Amparo Dávila (México)

Translated by Matthew Glesson and Audrey Harris

When Amparo Dávila died in April 2020, México lost one of its greatest writers.

In the 70 years of her career (she published her first book in 1950) she drew from her own dark family history (she was the only one of her siblings to survive until adulthood) and the world around her to write stories about madness, danger, and death.

While her work is hard to come across outside of Mexico (even in Spanish speaking countries!), this one collection has been translated into English and the translation is fantastic.

The Houseguest and Other Stories includes twelve stories taken from three of her collections, so you can get a sense of her style and themes: loneliness, obsessions, and fear.

The worlds in her stories are filled with terrible and mysterious things, and her characters appear to be powerless on the face of such horrors.

The title story has the main character fighting against a mysterious force that her husband has brought home, a presence that seems to be absorbing the house itself, in a way that reminds me of “House Taken Over” by Julio Cortázar.

A lot of her stories deal with housewives and the horrors they face seem to echo the constrictions put on by Latin American societies in the 20th century, and she uses this very abstract style of horror to reflect the anxiety of women in such a world. She was a truly fantastic writer, and she is sorely missed.

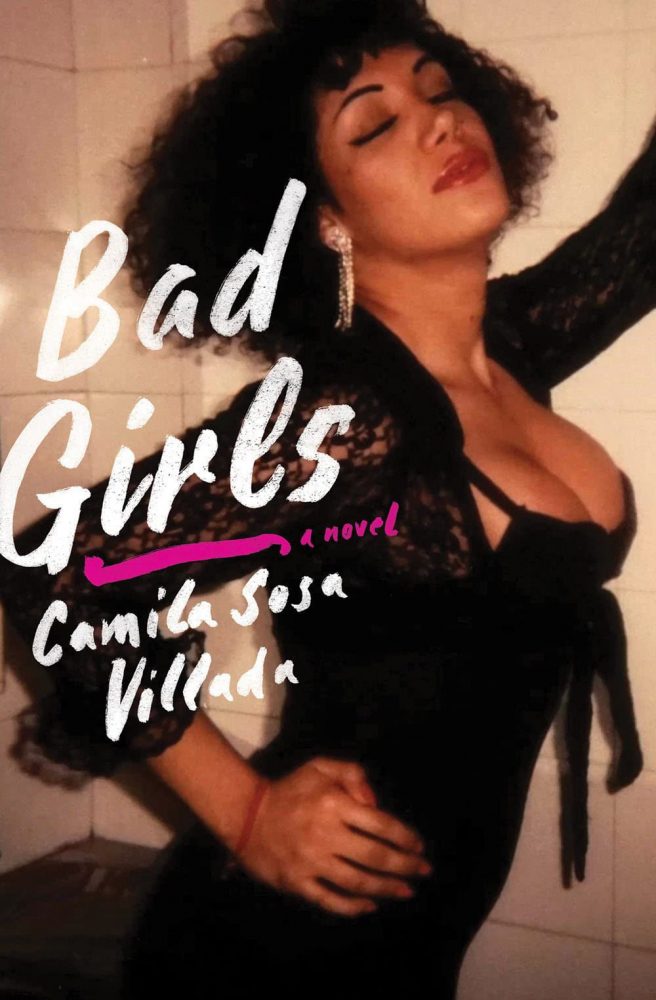

Bad Girls by Camila Sosa Villada (Argentina)

Translated by Kit Maude

Camila Sosa Villada was the first trans woman to win the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize (which is like the Women’s Prize for Spanish language writers) in 2020 with this absolute gem of a novel.

Centred around a group of trans women in Argentina sometime in the nineties, this novel deals with both pain and joy in a beautifully devastating way.

In the beginning, the women find a baby abandoned in the park where they work.

From that point on, the novel explores their different stories, their joys, their pain, their loves, and the family they all build together with their friends and lovers.

While Argentina is often considered to be a relatively socially progressive place, trans women there are disproportionately more likely to be the victims of hate crimes and discrimination in the workplace.

A lot of them, like the characters in this novel, turn to sex work to make a living, often in dangerous conditions. Camila Sosa Villada herself, when she was a student in Córdoba, did sex work to survive.

And while the realities that are shown in this novel are harsh and terrible, she also shows all the beauty and happiness in the love these women share for each other.

It’s really a beautiful novel, one that sheds a light over the experiences of women who are extremely marginalised and vulnerable, but also about finding a family based on love and acceptance in every way possible.

Jawbone by Mónica Ojeda (Ecuador)

Translated by Sarah Booker

Good Lord, is this a dark and twisted novel.

Fernanda, a student in a posh religious school in Ecuador, wakes up and realizes she’s been kidnapped by her own teacher, Miss Clara.

Fernanda and her clique of morbid girls have been torturing the poor woman for months, and it seems she has finally snapped.

The rest of the novel introduces us to the group of friends: Ximena, Analía, Fiorella and Natalia, as well as the ringleader Anneliese.

I’ve always found books about teenage girl friendships to be fascinating, especially when confronting the darkest aspects of it, so this book was right up my alley, especially since the characters here seem to have some sort of witchy coven that binds them all together.

There is also a sort of homoerotic bond, particularly between Fernanda and Anneliese, who share a relationship that appears to turn more obsessive and sinister as the book progresses.

The narrative is also filled with pop culture and literary allusions to all types of horror, including creepypastas, placing this novel firmly in the internet era.

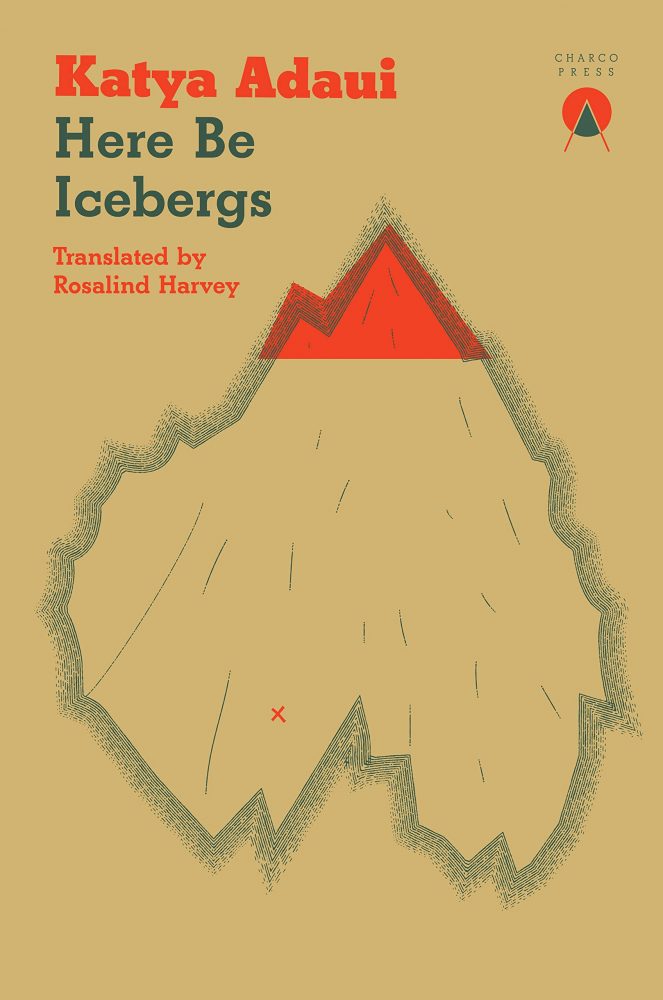

Here Be Icebergs by Katya Adaui (Peru)

Translated by Rosalind Harvey

Katya Adaui is a Peruvian author who has studied in New York, Paris, and Beijing. Here Be Icebergs is a short story collection that examines the nature and messy complexities of family life.

Narratively, these stories are fascinating. They mimic how we related to and talk about our families: random, biased, out-of-order stories and opinions about the people we love and hate.

The stories are tiny little vignettes; glimpses into the minds and memories of people with difficult family dynamics, traumas, and haunted memories.

These stories so closely reflect not only how we experience life with our parents, sisters, friends, and neighbours, but also how we relate those stories to one another; the lies we tell ourselves and the fears we experience alongside our experiences.

There’s power in the minimalism here. There is so much left unsaid, just as there is when we discuss our own families. There is also equal attention given to found family as there is to blood family.

Few writers are able to capture the rough complexity of family in the way that Adaui has with Here Be Icebergs.

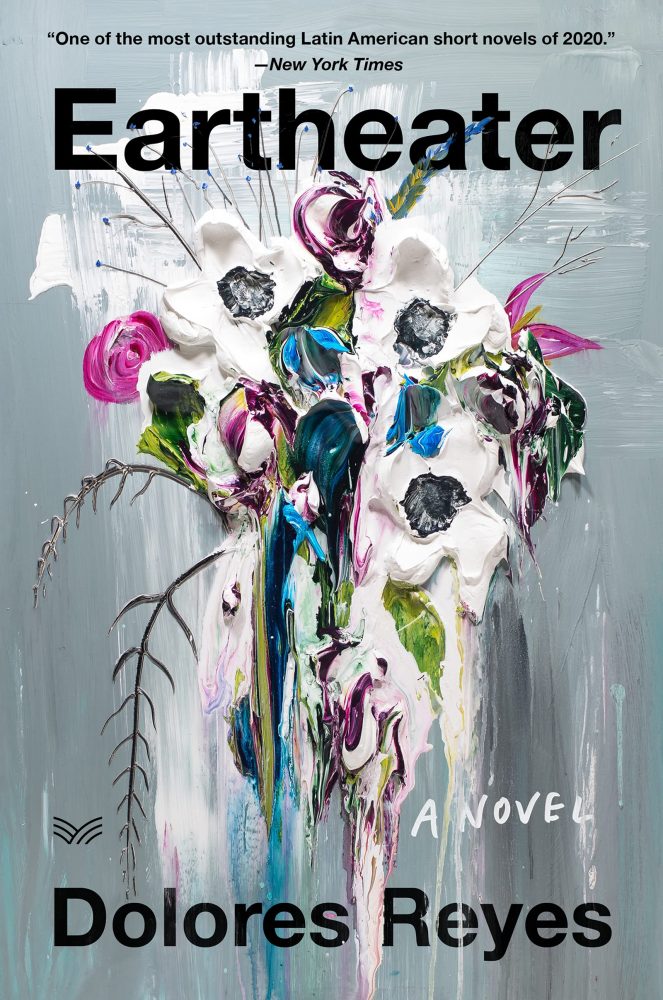

Eartheater by Dolores Reyes (Argentina)

Translated by Julia Sanches

While we’re still on the topic of very dark books, let’s have a word about Dolores Reyes’ Eartheater, in which a young woman eats some dirt and receives a vision about how her father had killed her mother.

In a continent devastated by domestic violence, this power proves to be useful and soon Cometierra is accosted by dozens of people who want to know about their missing relatives, mostly women.

As she is confronted by the absolute darkness of the life in the margins, Cometierra isolates from the outside world, disturbed by the violence and suffering she sees everywhere.

Born out of the #NiUnaMenos movement (“not one woman less”), this novel explores the realities and horrors of the lives of women in Argentina, and Cometierra is a fascinating narrator for such a story, thanks to the way in which she uses the language of the streets in a manner that is often surprising and deeply sincere.

She is a young girl from a bad neighbourhood, and her words reflect that. Her world is also very real, highlighting the ways in which the police does little to help the missing women and their families.

Cometierra becomes then a strange prophet, as she decides to take on the pain of others and turn it into a possibility for catharsis.

How to Order the Universe by María José Ferrada (Chile)

Translated by Elizabeth Bryer

María José Ferrada started out as a children’s author, with illustrated books that deal with Chile’s recent history in ways that kids and teenagers are able to understand and relate.

She has written two adult novels, both of which deal very specifically with child narrators and how they see the world around them, which of course is tinted by their innocence.

How to Order the Universe was her first foray into this type of fiction, and it is a beautiful book, very nostalgic and bittersweet, and despite being a short novel, it manages to pack a punch and strike directly on the feelings.

The plot is fairly simple: a young girl accompanies her dad, a travelling salesman in his business trips around Chile in the 1970s.

If you know anything about Chile in the 70s, you can probably imagine that, as the novel progresses, the narrator is progressively confronted with the horrifying events of those years.

The historical context mostly stays in the background, however, as the main focus here is the relationship between the narrator and her dad, who seems to be a bit of a dreamer, always promising the impossible to his daughter.

He also seems to be trying to sell himself a fantasy, but as the novel progresses it becomes more and more apparent that it’s just a dream, a pretty illusion that won’t come to anything.

It’s a beautiful novel about the relationship with our parents, the lengths they can go to protect us from the ugliness of the world, and that moment when we start seeing them as humans, rather than parents.

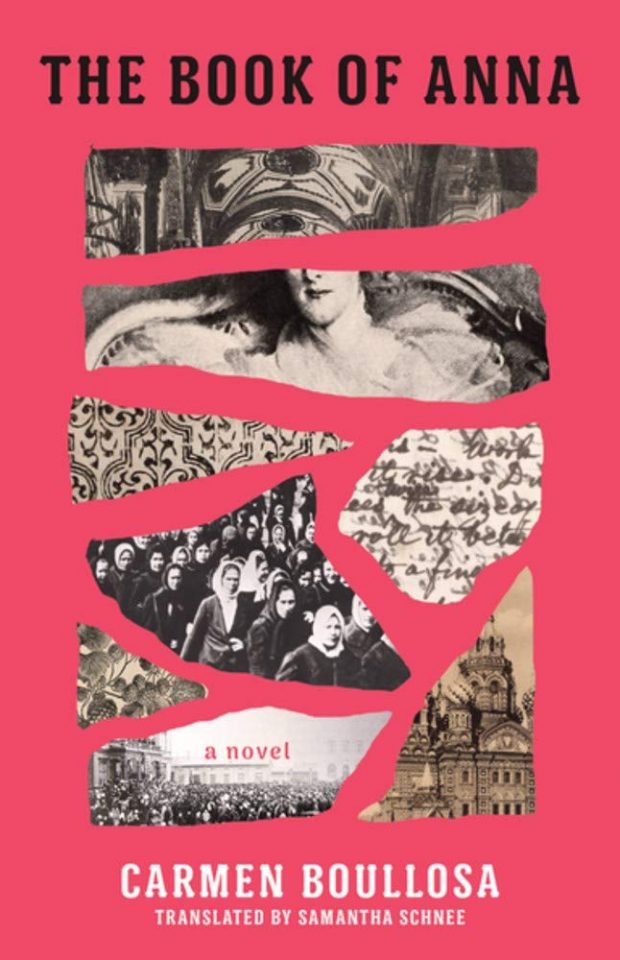

The Book of Anna by Carmen Boullosa (México)

Translated by Samantha Schnee

I have a massive soft spot for classic Russian Literature, and Tolstoy is one of my favourite writers ever. Anna Karenina, however, was a book that I had a hard time reading and enjoying the first time around. It took a second and third reading (and a course in Russian literature) to make me “get” Anna.

She’s far from the silly love-obsessed woman I thought her at 18, but a more complex and nuanced character that longs for a life in which she can do something, anything.

She writes a book in the novel, which is a very small detail that most people tend to ignore.This fictional book is at the centre of The Book of Anna, which presents itself as a sequel to that classic.

While it is very far from Tolstoy luscious style, Boullosa explores the lives of a bunch of characters, starting with an anarchist girl who leaves a bomb in a train in Saint Petersburg, and going on to Anna’s two kids: Sergei and Annie.

Both have lived their lives under the shadow of their scandalous mother, and it is her, once again, the one who sparks the plot.

After a request from the Emperor to purchase a portrait of dead Anna, Sergei finds an opportunity to get rid of that reminder of their family’s trauma, while at the same time bringing her back into the public eye.

The portrait, hidden away in the family’s attic, also hides the pages of the story written by Anna, a fairy tale that echoes Russian folklore.

Anna, while dead, is very much at the heart of the narrative, as everyone seems to have a different opinion on her and her legacy, and her secret book seems to be the only key to her, that remains far away from the public.

Boullosa’s novel is not going to be everyone’s thing (it was mine, though, but I am obsessed with Tolstoy), but it is fascinating in the ways the characters are connected through the past and fiction and reality merge in unexpected corners.

On Lighthouses by Jazmina Barrera (México)

Translated by Christina MacSweeney

I’m not sure there is a lot of non-fiction translated into English from Spanish. It’s rather interesting, considering the long tradition of the “crónica” in Spanish-language literature, but here we are.

I’ve given as a present and recommended a few times, as it is fantastic in many ways, especially for Barrera’s amazing command of words and emotion, even in non-fiction.

Jazmina Barrera is a Mexican essayist (though her first novel came out recently in Spain), and this book lives somewhere in the realm of travel books and a history of lighthouses. I personally find lighthouses fascinating, even if only in an abstract way.

On Lighthouses chronicles Barrera’s travels to different lighthouses all over the world, while being at the same time a meditation on the role of lighthouses through history and how their keepers play such a silent and fascinating book, beautifully written and quietly meditative.

It’s also very short, so anything more I say about this will be redundant. You should pick it up if you want to read something different and unique.

Her newest book at the time of writing Linea Nigra, is a meditation on motherhood and writing that has been on my TBR list for a while.

Seeing Red by Lina Meruane (Chile)

Translated by Megan McDowell

Lina Meruane is one of those authors that inevitably intimidate me. Her books aren’t long, but they are very challenging on the emotional level, as well as being somewhat abstract.

This novel in particular, as the character loses her sight in the first few pages, exists in a world where sight has disappeared, and the narrator uses memory and her other senses to navigate her life.

She is an international student in New York, and with a stroke, her life changes completely, from being used to rely on her sight for most things, to being heavily dependent on her partner for even basic things.

And then she travels back home to Chile, where her parents fuss over her, highlighting her loss of independence and the growing vulnerability of her position.

It is a dark novel, literally so, but Lina Meruane’s pen manages to bring forward smells, textures, and sound.

Because of the style in which it is written, we get a close look at the narrator and her thoughts, and at points it gets so intimate you need to put the book down for a little while.

Optic Nerve by María Gainza (Argentina)

Translated by Thomas Bunstead

Optic Nerve is a book that sort of jumps across genre, between essays and fiction. Gainza, like her narrator, started out as an art critic, and this book is centreed on gazing.

The narrator is obsessed with art, so it very literally colours the way in which she sees the world, and how she relates to it.

If you like plot-driven books, this might not be your thing. The narrative is rambling, with the narrator going from certain events in her life to the lives and works of famous artists throughout history.

In her brain, her life and art are inextricably entwined, so she can see all the connections through art. It’s fascinating and disjointed, and it clearly showcases how passionate Gainza is about art.

It reminded me of whole afternoons exploring museums and getting to see the city.

Kalpa Imperial by Angélica Gorodischer (Argentina)

Translated by Ursula K. Le Guin

This is a really special book, translated by the one and only Ursula K. Le Guin. Her work as a translator is not very well known, but she did translate Gabriela Mistral and Angélica Gorodischer from Spanish into English, and she did a great job with both.

This book is alternatively described as a novel or as a short story collection, but it’s really somewhere on the middle, with every chapter being about a different event in the history of the Empire of Kalpa, a long-lost kingdom with a colourful life.

Kings, Queens, wars, and all sorts of drama happen, and it is intertwined with some sections that deal with the maybe aftermath of this Empire. Possibly.

While there is a tendency to classify anything magical coming from South America as “magical realism” or “the Fantastic”, this one is straight up fantasy that echoes Tolkien’s fascination with world-building and creating a mythology.

But it is also like nothing I’ve ever read before, from anywhere in the world. The world is grounded in the fictional history she creates, and it makes up for a wonderfully vivid space.

I’m usually a character reader, and there isn’t much plot or character development here, but the uniqueness in these pages more than makes up for that and creates a fascinating perspective that feels truly magical.

The Touch System by Alejandra Costamagna (Chile)

Translated by Lisa Dillman

After Pinochet’s dictatorship ended, Spanish language publishing started looking at Chile with new eyes. A generation of writers came out then, with a literature that aimed at expressing the new ideas and feelings that were travelling across the country.

Alejandra Costamagna is one of the women who burst onto the literary scene (they were given a lot less press than the men, but somehow all the women have managed to still be relevant 30 years later, while none of the men are widely read now), and this is her latest novel.

Finalist for the Herralde Novel Prize (given by Anagrama, one of the largest independent publishers in Spanish), this book tells the story of a young woman, Ania, who is asked by her father to travel across the Andes to say goodbye to her uncle Agustín, dying in Argentina.

The novel jumps back and forth in time, exploring memory and family history as well as grief and love.

Interwoven with Ania’s trip we find typing lessons, letters, memories, and instructions for Italian immigrants traveling to South America, weaving a tapestry of love and loss, and the ways in which family shapes you even when they are far away. Absolutely recommended.

Forgotten Journey by Silvina Ocampo (Argentina)

Translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan

Most of the writers on this least are still alive, but I also wanted to include one of the classics: Silvina Ocampo, youngest sister of Victoria Ocampo (legendary modernist editor in Argentina), married to Adolfo Bioy Casares, and close friend to Jorge Luis Borges.

While she was definitely in the literary world of mid 20th century Argentina, her work is often cast aside. Or at least it was until some time ago, when her writing started being rediscovered and revalued as a precursor to some of the most popular Argentinian writers now; Mariana Enríquez even wrote a literary biography about Ocampo (La hermana menor, 2014).

The stories in this collection are the first ones she ever published, and they are all quite short and surreal. Disembodied feet run on the floors of the flats above, girls who look eerily like each other meet and confuse their guardian angels, and circus performers become ordinary.

In her stories, which have a delightfully dark tone In terms of atmosphere, she reminds me of a less wordy Angela Carter, and that comparison seems to be particularly apt, as both authors are inspired by fairy tales and folklore to construct their stories.

They even both wrote Bluebeard retellings! Mariana Enríquez, wrote in Freeman’s that her own time wasn’t ready for Ocampo’s mixture of the insanity of Angela Carter and Clarice Lispector’s originality. I think we might be ready now.

Dislocations by Sylvia Molloy

Over less than 100 pages, across a series of small vignettes, Argentinian author Sylvia Molloy traces a person’s experiences and feelings as they watch an aged friend fade away from dementia.

This friend, named M.L., is visited often, and her memories are observed and pondered over. Each vignette considers something personal, linguistic, or philosophical.

Our protagonist considers who M.L. is and was, why she remembers what she does, what time feels like to her now, and why she does the curious things she does, such as make up new words.

Molloy asks, and encourages us to ask in turn, questions of time and friendship, personality and persona. She explores the nature of the mind versus the body, and she does all of this with so few words.

Not a moment or a thought is wasted as Molloy plunges into the depths of her own thoughts and imagination, her own memories, and those of M.L.

Sylvia Molloy is a legend amongst Argentine writers. To quote Mariana Enriquez, she is “One of the most lucid writers of Latin America.”

Of Cattle and Men by Ana Paula Maia

Written by Brazilian author Ana Paula Maia and translated into English by Zoë Perry, Of Cattle and Men is a short, visceral, discomfiting novel about the cycles of capitalism and the people at the very bottom.

Our protagonist, Edgar, works at a slaughterhouse; his job is to hit the cows over the head with a wooden mallet before they are killed.

Edgar is devoutly religious, and has a strict moral code of his own. Before the mallet comes down, he says a prayer for the cow’s soul.

His code leads him to do everything — up to and including murder — if he believes it to be in service of what he sees as good and right.

Of Cattle and Men is what you’d get if you placed the characters and themes of a Steinbeck novel into the cold and bleak world of a McCarthy novel.