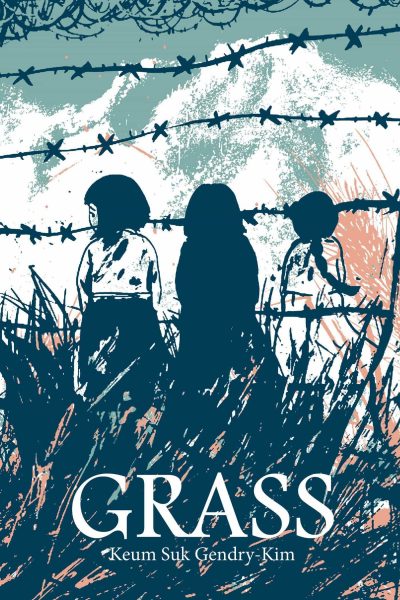

Grass is a starkly beautiful graphic novel which reveals the true-life story of a Korean ‘comfort woman’ during the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945. The occupation ended after the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II, following the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Grass is a timely and gravely impactful comic book that works in part as a protest against Japanese president Shinzo Abe’s recent downplaying of the existence of ‘comfort women’ during the Japanese occupation. Often, as you read this book, you’ll hear the choked and raw voice of Lee Ok-sun, the ‘comfort woman’, fill your skull with cries of, “If comfort women didn’t exist, Abe, then who am I?”

Grass

Keum Suk Gendry-kim, creator of Grass, remarked in her afterword: “I resolved to try telling her story in a calm and even tone. No matter my position, I avoided sensationalising the violence, pain, and suffering of the characters.” This approach to the retelling of Granny Lee Ok-sun paid off in spades.

What we have here is a result of her painstakingly crafting an honest, moving tale, using only the truth, and telling it in such a way that will effortlessly move the reader to tears but does not cloud the truth with distracting emotion and drama. It’s a grisly but stoic, blunt, poignant, gripping, and enraging tale of one woman’s survival as a victim of kidnapping, abuse, and rape during a time of imperialism and war.

The story of Grass begins a little jumbled, narratively and chronologically, but the initial confusion serves to disorientate and unbalance the reader effectively before the stark and impactful tale truly begins.

Grass opens not at the end, nor at the beginning, but at a significant moment in Lee Ok-sun’s life as she, who has spent fifty-five years living as a wife and mother in China, is at last able to return home in the winter of 1996. From there, we rewind to her childhood in 1934 rural Busan, during the Japanese occupation of Korea.

We are introduced to her poor family and the difficult, miserable life she was born into. Lee Ok-sun has had no schooling and cannot read nor write. Soon, her parents offer to send Ok-sun to live with a family in Busan city, where she will get a chance to at last attend school.

Though, in fact, she does not, and this was never their intention. She is worked to the bone, used as little more than a slave girl, and moves from place to place doing whatever work is forced on her and trying to stave off exhaustion and starvation.

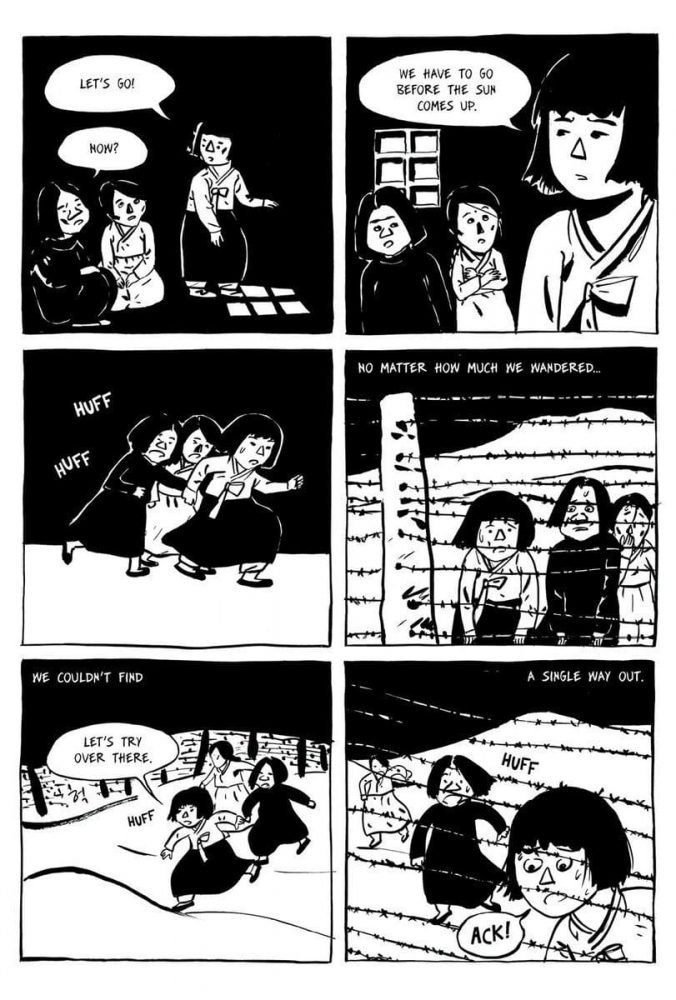

Abruptly, at the age of fifteen, Ok-sun is kidnapped in broad daylight and thrown into a truck with other kidnapped teenage girls. The truck takes them to a train and the train carries them off to Japanese-occupied Manchuria (known to the Japanese at the time as Manchukuo).

There, she is thrown into a ‘comfort station’ at East Yanji Airport to be used as a tool – a doll – a sexual toy to ‘service’ Japanese soldiers. It’s 1942, and there she would remain until the end of the war in 1945. For those three years she would suffer through countless rapes, beatings, and even have her life threatened as she contracts syphilis.

Lee Ok-sun’s is a harsh, grim, and stripped-bare tale that pulls no punches. It’s a true and honest depiction of one of countless ‘comfort women’ who were used as ‘sexual slaves’ in the service of Japanese soldiers during that time. But it’s not a tale that leaves the reader feeling entirely hollow.

Grass cleverly presents its writer and creator to us, through flash-forwards to today as Keum Suk Gendry-kim is interviewing Granny Lee Ok-sun, now living out her twilight years back home in South Korea. This framing device allows us a three-dimensional perspective of the story.

Knowing up-front that Granny Ok-sun survives the occupation, is liberated, lives out her life in China, gets married, has children, and eventually returns home – it all provides a sort of pre-emptive catharsis. We are excited to see her survive, thrive, prove that her strength as a young woman outlasts and defeats that of the Japanese empire.

It’s a story that asks us to carry the weight of our anger, our frustration, and our upset as we follow her through all of this tragedy; but it also alleviates that weight by giving us hope, and allowing us to be inspired by Ok-sun’s sheer ability to survive.

Keum Suk Gendry-kim’s decision to depict Granny Lee’s story as a comic book was a wise and visionary one. Grass joins the impressive pantheon of legendary biographic comic books, proudly shelved alongside such works as Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and Art Spiegelman’s Maus.

There is a second layer of truth, a deeper revealing of history, in graphic biographies. It is as though, in the blending of fact and graphic interpretation, a greater truth is revealed, blending what is real and what is imagined and interpreted.

Through the medium of comic books, we are able to see deeper into these worlds, lives, and experiences than by simply relying on our own imaginations to form them as we read the cold words on the page.

At least, speaking for myself, I find the medium of graphic biographies – whether they be grand in scope and scale as Grass is, or small and intimate as Kabi Nagata’s My Lesbian Experience With Loneliness is – to be something wholly precious as a form of storytelling. Grass is exemplary in this regard, and should be held up as the new standard for graphic biographies.

Read More: The Best Translated Asian Graphic Novels

To speak on the art specifically, for a moment, the effects of the thick black brush lines on the pure and snowy white page is deep, almost provocative. It brings to mind the traditional art of calligraphy in moments where the book’s characters exist as singular things floating in white space.

There is a dichotomy at play in the use of empty white, as though the infinite space implies endless freedom but is, in fact, an entrapment. Like being caught in the snowy wastes of Siberia – a freeing and open expanse that, in truth, entraps and threatens anyone who finds themselves there.

The art takes a subtle but truly hefty turn whenever it depicts grass, trees, springtime natural beauty. There’s a flippant, carefree, unconcerned feeling to the manner in which the grass and trees are drawn here.

While the faces and bodies, the buildings and planes and streets, are all drawn with precision and tightness, the natural landscape flows haphazardly and indiscriminately – a reminder that nature cares not for our woes and our systems of suffering: on it goes, flourishing and fading and flourishing again. It’s a cold winter in Japanese-occupied Korea and China, but all the while through Grass, we are waiting for the spring to come.

Conclusion

Keum Suk Gendry-kim’s accomplishments through Grass cannot go understated. In meeting Granny Lee and penning her story, bringing it to live through raw artistry that blends the abstract and the minimalist, she has done something truly great.

She has protested against the political purification attempts of the Japanese government. She has told a story which represents the untold true lives of countless women. She has shown her own truth as a skilled, visionary graphic writer and creator.

This story will exist loudly and proudly in the face of attempts to shamelessly wipe clean the dirty history of colonial Japan. It gives an international voice to a quiet old woman who has survived so much and roared in the face of true pain and fear and misery. It’s artistry in a form that I, at least, have the highest love and respect for.

And I couldn’t be more grateful to Keum Suk Gendery-kim for telling this story, and to Janet Hong (who also translated the wonderful Bad Friends) for so faithfully translating not only her words, but their impact, their clarity, their truth.