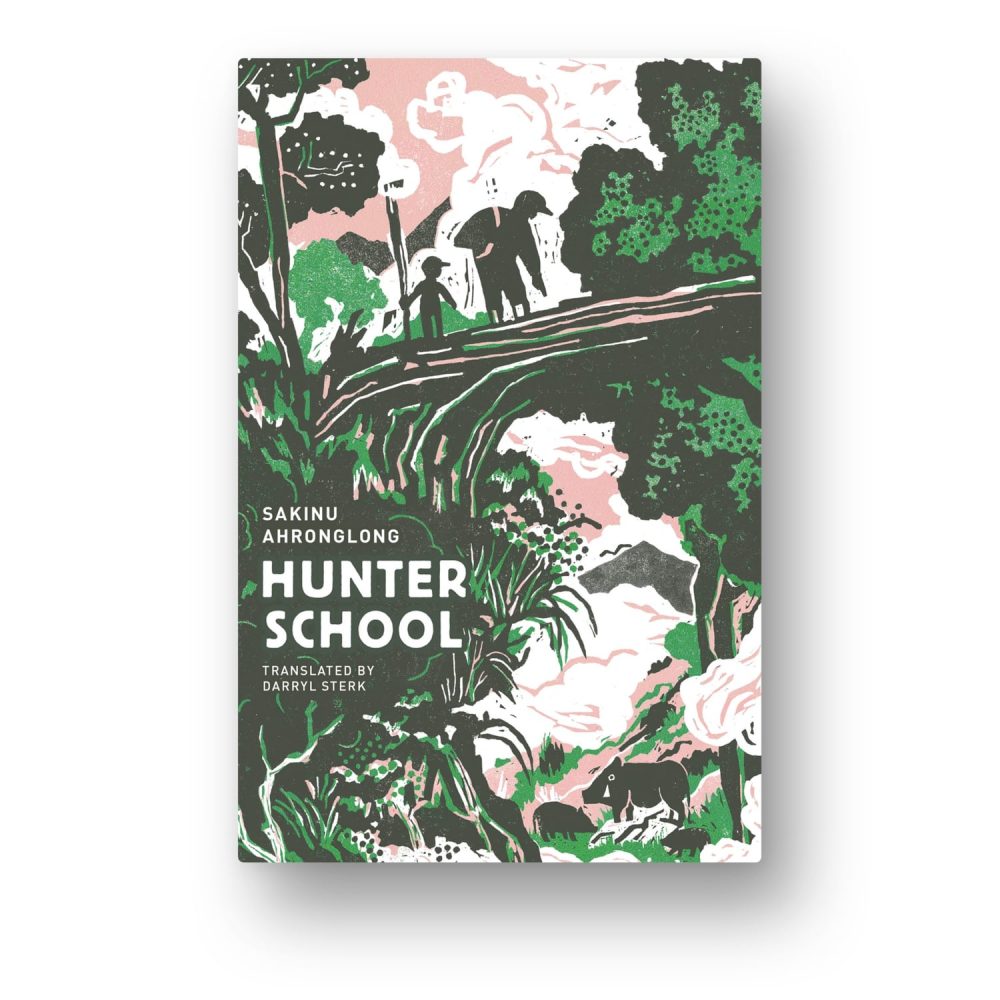

Translated from the Mandarin by Darryl Sterk

Those of us who read a broad spectrum of world literature in translation often do so in order to broaden our perspectives, understand other cultures’ ways of writing, processing the world, and expressing themselves through art.

With Taiwan being one of my favourite countries and cultures, I’ve read every Taiwanese book in translation I can get my hands on. But what happens when a book is published which takes you even deeper into the culture, politics, and history of a nation you thought you understood? It can be an entirely transformative experience, and that’s exactly what Hunter School is.

Like I said, I love Taiwan. It’s a country very close to my heart. I sympathise with the nation’s political frustrations and applaud its progressive and inclusive politics.

There’s always more to learn about a country, however (that’s far from a revelatory statement), and Hunter School provides not only a doorway into an almost known world within the island nation of Taiwan, but also a new perspective on the history, traditions, and politics of a nation I have come to so fervently adore.

Sakinu Ahronglong is a member of the Paiwanese group of indigenous Taiwanese people who have populated the hills, forests, and plains of Taiwan since long before the Kuomintang or the Japanese occupation.

The story of their cultural deflation — a similar story to those of American Indians and Aboriginal Australians — is a tragic one, and groups like Ahronglong’s have had to compromise and give into modernity, industry, and capitalism in order to survive.

This was a group of people that I knew nothing about until reading this book. Even if Hunter School were bad, its value could not be understated or denied simply by virtue of what it has to teach us about the Paiwan people.

Fortunately, Hunter School is anything but bad. In fact, it is a transportive, uplifting, sweet, moving, and at times fantastical book which, while it follows one person’s narrative, shows an incredible breadth of emotion, tone, and even lessons to be learned.

The book achieves this breadth through its succinct, clear, and emotive language, as well as its structure. Hunter School is a short 160-page novel divided into three parts, with each part having multiple chapters made up of ten or fewer pages.

These chapters are true stories from the author’s life, mixed in with tales told by his parents and grandparents, as well as local folklore and traditions. Each one reads like a fable, relatively self-contained (though there is a clear chronological narrative) and with a clear and emphatic message tied to its language.

The story follows Sakinu himself as he retells his young life as a Paiwan native amidst the cultural shifts and changes in 20th century Taiwan. Part One is largely concerned with his childhood, one filled with lessons from his extremely talented hunter of a father.

Here, we learn about the traditional millet wine of the Paiwan people and the ceremonies surrounding it. The stories of Sakinu’s grandparents, the farm they tend, and the fables his father bestows on him about the native creatures of the hills and forests are nothing short of infectious.

These are real stories of real people that nevertheless take on a charming fairytale quality. Darryl Sterk’s translation here helps endlessly to provide a clear-cut tone that blends wide-eyed childish fascination with a grounded, sombre approach to change and the transience of life.

While Part One is a relatively contained narrative of Sakinu’s childhood, Part Two and Part Three blend together as a large serving of adulthood and modern life, with Sakinu telling stories of his life at sea, his father’s work in Taipei, and the almost complete collapse of their people’s peaceful and isolated way of life.

The romanticism of Part One eventually gives way to the harsh, rude, and unfair realities of modern life, a life their people did not build and do not deserve to be subjected to. And yet, changes beyond our control compel us all, in the end, to obey the rules of broader society.

It’s a tragic tale but one with a thread of hope running through it, made strong almost entirely thanks to Sakinu’s own willful dedication to tradition, family, and peace.

As someone with “progressive” and “liberal” political views, I’ve always viewed progress as ultimately good. Progress leads to scientific and medical advancements, social inclusion, fairness, an erasure of stuffy, harmful, and damaging conservative values.

However, Hunter School vividly teaches that the fight to maintain traditional values within a community can be a wholesome and positive thing when the values of that community are ones which practice peace, kindness, respect, and fairness.

Towards the book’s conclusion, we do admittedly see a lot of in-fighting and racism between the indigenous groups, but the lessons that the book, as a whole, has to teach prove to be ultimately revelatory. The TL;DR of this lesson is that progress is only necessary if we don’t have peace and fairness; if we are living in a toxic, unhealthy, unfair, unequal society.

If we are already living peacefully and fairly, as the Paiwan people have been for so long, progress is a moot point. Coming to understand this as I read Hunter School was akin to seeing the world in five dimensions, and I am forever grateful to Sakinu Ahronglong for that.

Conclusion

Hunter School is a rare book which deserves to be the opposite. It deserves to be on every single shelf of every single bookshop. And this isn’t simply because it has a lot to teach us about an underrepresented group of people but because it has so much to celebrate within its pages. Real life stories of real life experiences mixed with local folklore, history, and traditions.

This, woven into a raw and personal narrative of an indigenous Paiwan man in the 20th century, is a unique and must-read experience for any reader. Sterk’s gorgeous translation and the minimalist structure of the book also make it an enjoyable, easy, comfortable read for a single afternoon. There is nothing that’s less than wonderful here.