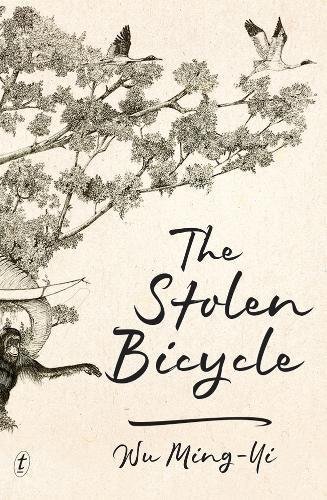

Translated from the Mandarin by Darryl Sterk

Wu Ming-Yi is Taiwan’s most celebrated author, and at the time of writing, only two of his novels have been translated into English (The Stolen Bicycle, and The Man with the Compound Eyes).

Longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize 2018 (alongside Han Kang’s illustrious The White Book), it’s certainly my hope that the acclaim this book is bound to shower him with will allow the English speaking world to experience all of Wu’s writing.

If his other stories are half as captivating and revolutionary as this one, they deserve to be enjoyed the world over. This novel is translated by Darryl Sterk (who is translating Honford’s Stars upcoming book Scales of Injustice). So why did we love this book so much?

Learning Through People

As someone who grew up in the deep quiet of the English countryside, living in an idyllic village bordered by a dense forest and actual rolling hills, I felt so very detached from the things which I believed truly mattered. “There must be more than this provincial life,” is one such original thought I recall having.

After growing up, passing through the digestive system of adolescence, and emerging a fully-formed adult, I would take the occasional trip home to see my parents. On one of these trips I spoke to the (now late) Mr. Farmer, a man whom my mother had known for many years. As it turns out, the man I’d known in passing as a child was a survivor of a German PoW camp during WWII.

He had a deep well of rich tales to tell, and as a pompous child I had not once considered asking him about his own life. What a wasted opportunity.

Living in Shanghai afforded me a roundabout way of remedying this mistake. I was lucky enough in my job to have the opportunity of tutoring a number of educated, wealthy, exciting individuals who had moved to Shanghai from as far afield as Taiwan and Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang province.

And therein lies the lesson, and the perhaps overly lengthy connection to this novel: we are all, each one of us, a big bundle of tales and memories and perspectives.

Learning Through History

This concept lies at the heart of The Stolen Bicycle. This and Wu Ming-Yi’s encyclopaedic knowledge of bicycles, butterflies, and Taiwanese history. Blending and blurring memoir with fiction to produce an intimate journey through 20th Century Taiwan, Wu has done something few authors would dare attempt.

Framing the tale around the disappearance of his protagonist’s father, Wu introduces us to a motley crew of eccentric, empathetic, and captivating characters. As he follows the ownership trail of his father’s bicycle in hopes of finding the truth behind the man’s disappearance, Ch’eng uncovers the personal histories of each of his new acquaintances.

Through these histories we are taken on a journey through the jungles of Burma during World War II, are taught the ins and outs of butterfly scholarship, and weave through the intricate relationships between Mandarin, Taiwanese, and Japanese languages.

“[…] thih-be—iron horse. Such a beautiful expression, evoking both the natural world and human endeavour! Imagine the Creator laying down seams of iron-rich rock for people to mine and cast into carbon steel in the shape of a horse.”

The Stolen Bicycle is a wild beast of a book, daring to turn itself inside-out, pacing back and forth and clawing at its edges, rejecting the traditional pace and form we come to expect from our contemporary literature. Like the perfecting of a craft (say, bicycle design, for instance) or survival in a war-torn nation (possibly Burma), this tale is not a smooth one. Oftentimes it is not a tale at all, but something closer to a history book or a biology text.

Learning Through Stories

Our man, Ch’eng, is an author and a journalist, and he tells the stories of those he meets just as a journalist would, as he weaves these disparate narratives into his own desperate search for truth and understanding.

Throughout Wu’s writing there is a heavy sense of pragmatism, wherein Ch’eng shows his strengths as a journalist by distancing himself from the feelings of his characters, instead choosing to tell their stories faithfully and use them as a means to an end.

All the same, it is a testament to Wu’s adeptness at the craft of writing that he is able to paint a cast of characters as broken, tired, and sorrowful, and present them to the reader through the eyes of a man all at once distracted and attentive, honest and doubtful.

“Sometimes I wonder what kind of job it is, being a writer, and why society allows a particular group of people to take writing—a semiotic system humanity invented for entirely different purposes, and use it to make their living telling stories. And how do the people who do this job get away with bending, forging or casting words so as to excite, haunt or even torment their readers?”

If you like the sound of this you may also like: The Travelling Cat Chronicles.

Ready to explore Taiwan? Take a look at our day trips.