Translated from the Mandarin by Darryl Sterk

Living in twenty-first century Korea, the animosity levied against Japan by much of the population still holds true today, even amongst many young people. This animosity of course stems from Japan’s occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945.

Such hostility is arguably understandable, but one article that appeared last year in the Japan Times described Taiwan, a nation also occupied by the Japanese Empire (1895-1945), as having a far more affectionate relationship with modern day Japan.

One Japanese businessman who made the recent decision to move from Japan to Taiwan described in the article how his life came to be drastically improved: “I’m gay, and that was a pretty miserable predicament for me when I was living in Kumamoto,” he said. “I couldn’t find a partner and I knew my family would never understand. But life in Tainan was a complete game-changer.”

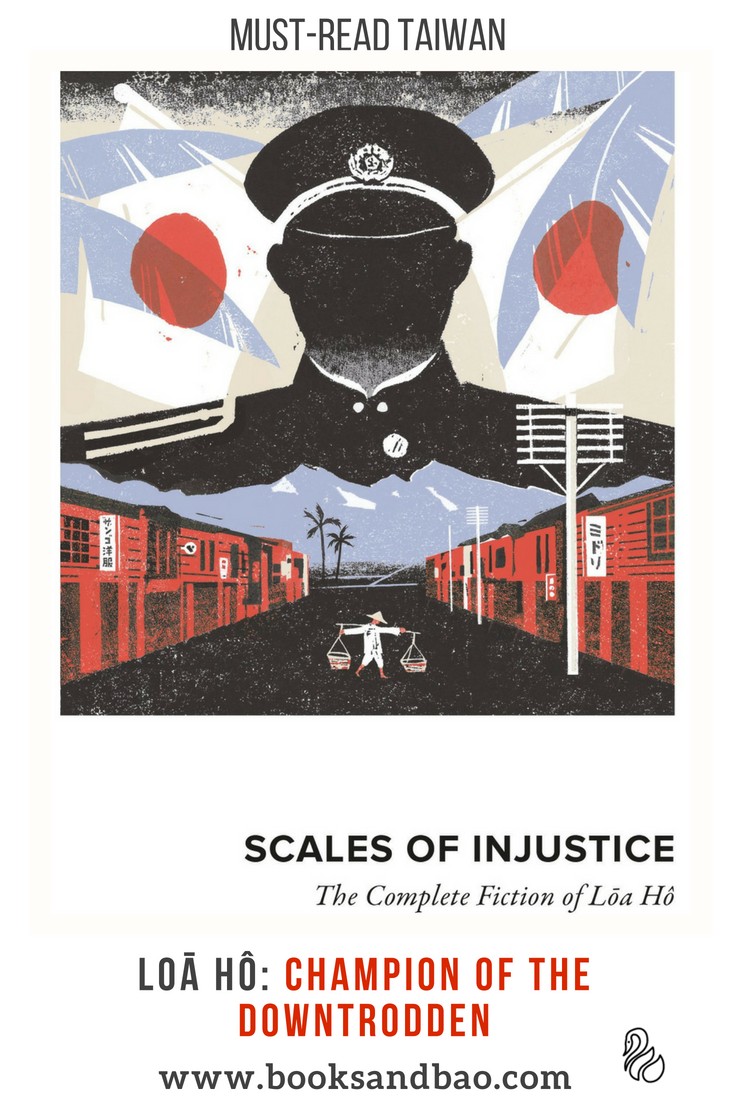

All that being said, Japanese-occupied Taiwan was certainly not a place of warmth and community, and doctor-turned-poet Loa Ho captured life in early twentieth century Taiwan through passionate, satirical, and thought-provoking prose.

Scales of Injustice

Now famously regarded as the ‘Father of New Taiwanese Literature’, Loa Ho’s complete collection of prose has been painstakingly translated by the deft and poetic hand of Darryl Sterk, translator of the recent captivating novel by Wu Ming-Yi, The Stolen Bicycle, and published by Honford Star, a house that is quickly establishing itself as a gift to the world of literature as they breathe new life into the once-lost-but-now-found works of so much of East Asia’s literati.

Loa Ho was a champion of the underdog in Japanese-occupied Taiwan. With a style and keenness comparable to that of Charles Dickens, and a distrust and hatred for systems of government and class to mirror that of Karl Marx, Loa Ho wielded with confidence his sardonic wit as a weapon against the established systems which formed the muddled and broken mess that he saw his Taiwan to be.

“The secret of a rich man’s happiness is the poor. Indeed, that is their purpose: God made the poor for the sake of the rich.”

The stories told by Loa are imbued with a palpable rage, but to read them is to often laugh and remark at the absurdity of their situation.

Some tales, such as The Poor Thing Died will leave the reader in tears, while others, such as Mr. Snake and A Disappointing New Year, while demonstrating true tragedy, are told with such melodrama and subtle absurdity as to make us laugh as we would at an episode of South Park or a Terry Pratchett novel.

The character of Daijin (in Japanese literally meaning ‘great man’) Sa, the protagonist of A Disappointing New Year, is a police patrolman saddened by a lack of oseibo gifts from the public come New Year’s Day, and blames this shocking level of disrespect on a socialist activist who has taken to the stage and is spouting such filth as:

“The tradition whereby officials were exalted and the common man was meek was based on ‘feudal thinking’ and had no place in a constitutional society”.

But Daijin Sa demonstrates a comical level of incompetence and rash anger in his lack of professionalism that brings to mind characters like The Simpsons’ Chief Wiggum or the cast of Super Troopers.

At the other end of the spectrum are moving tales of sorrow and abuse. The Poor Thing Died is arguably a work of feminist literature, telling the story of the poor concubine A-Kim who, as the book’s introduction remarks, is treated as a commodity, up to her accidental death.

And in this story which serves to highlight the pain of life for so many poor women of Taiwan, Loa Ho’s affection for the underdog in all its forms is front and centre, as is his distrust of power and capital.

“Now in this nasty society, at a time when capitalism has reached its apex, it goes without saying that A-Kim could not escape the demonic power of filthy lucre.”

To go into greater detail concerning the impact of the stories would be to undermine the excellent introduction to this collection, written by Pei-Yin Lin of the University of Hong Kong.

While perhaps best saved for after finishing the book, the introduction serves as a fantastic story of Loa Ho’s life and his beliefs, as well as an analysis of each story found in this collection.

Found in Translation

The stories found on these pages are each thematically shaking, bringing to question the risks that Loa Ho must surely have taken to get them to print. But none of this could have ever been enjoyed without the skill and dedication of Darryl Sterk.

I certainly don’t wish to gush and fawn pathetically, showering Sterk with praise (though if ever were I to meet him, I’m sure I wouldn’t be able to help myself), but in the world of translation his skill at the craft cannot really be overstated. Sterk is a man who understands people well; and translation aside, he is a thoroughly accomplished writer.

A good translator does not simply translate well, but also adapts the thoughts and emotions conveyed by the author to ensure that they are understood and felt fervently by audiences of differing cultures and backgrounds. Sterk does this better than perhaps any translator I know of.

When a line strikes me as poetic and lyrical, I do not think first of the writer, but of the translator and their ability to convey the tone and lyricism of the line perfectly into English. Sterk is damn good at this. Damn good.

“Thin is the horse that won’t eat night hay, poor is the man who won’t make a dishonest dollar. […] A small fortune is down to hard work; a great fortune is up to heaven.”

The more I write, the more my deep affection for this collection shows, perhaps to the point of seeming erratic. But let’s say this is simply testament to the skill and power on show here. The socialist vehemence of Loa Ho’s storytelling and the poetic beauty of Darryl Sterk’s translation has mixed perfectly to create an anthology that deserves to be read by audiences across the English-speaking world.

These timeless tales of the downtrodden and the oppressed are worthy reading for anyone who has ever suffered any kind of misfortune at all, which, of course, is every last one of us.

You can purchase this novel here.

Check out our review of Honford Star’s other books: Sweet Potato, Endless Blue Sky, and The Underground Village.