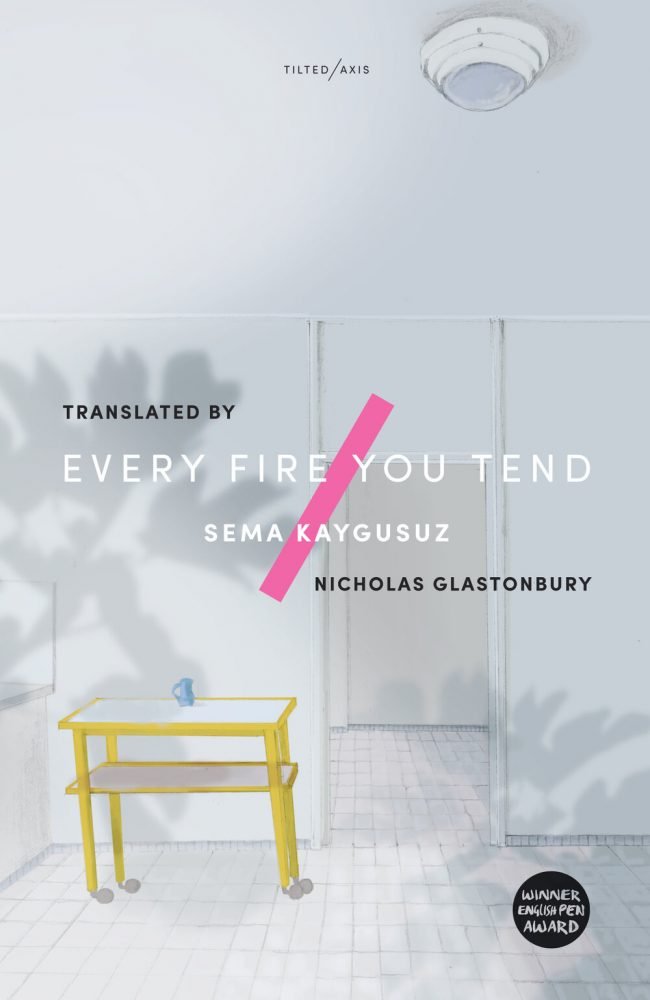

Rather than digging into the necessary and fascinating history surrounding Every Fire You Tend right off the bat, it’s perhaps more important to lead with this: Every Fire You Tend is an astonishing work of art.

An experimental piece of storytelling that blends fact and fiction, history and folklore, religious parables and superstitions, to create a narrative that takes the reader stiffly by the hand and guides them, running, through tales both sweeping and intimate which, by the end of it all, will have you ultimately changed.

This is a book that has a lot to teach; and it goes about it with astonishing poetic and lyrical wordplay (Nicholas Glastonbury is an infinitely gifted and dedicated translator). Arriving late in 2019, this book should not be overlooked as one of the finest novels in translation of the whole year.

Every Fire You Tend

Sema Kaygusuz is one of the most vital voices in the Turkish literary scene; a daring and bold writer in a nation that, historically, has not enjoyed daring and bold moves by its people.

Case in point, the topic of Every Fire You Tend. This book traces the very real – though very much scrubbed from the Turkish history books – cultural genocide of a group of Alevi Kurds who lived in a relatively isolated community in the Taurus Mountains known as Dersim.

This cultural genocide occurred in 1938 and resulted in the transformation of these people into nomads desperately searching for somewhere in Turkey where they could safely settle as they spread themselves out across the land as best they could, like an old body falling apart; and thus, their culture’s flame fizzled out. With Every Fire You Tend Kaygusuz informs and reminds us of these people: their traditions and their very existence.

This is not, however, a history book. It’s something with a lot more strength than that. Reading the first few pages can be a disorientating experience, as the narrative is predominantly told through the second person, a mechanic we don’t really see in literature.

We have a nameless and shapeless narrator who is speaking to another. They are in modern Istanbul, and the narrator spends her narrative reminding the other of her own personal experiences, the life of her grandmother Bese, and the history of Bese’s people: the Kurds of Dersim.

The book’s enigmatic allure is the identity of the narrator. She speaks to the ‘other’ in a berating tone, educating her about Bese and the forgotten Dersim people who have been erased from history. The narrator is angry. The silent protagonist being berated, and the angry narrator, are very possibly one and the same.

Perhaps the protagonist is writing a letter to herself; the narrator is a character created by the protagonist to voice her anger at herself and at her country; she is, perhaps, her conscience. Whatever the case, this mechanic is utterly compelling. It’s a technique utilised so spectacularly as to be enough of a page-turning device in its own right, plot and narrative aside.

“You were the protagonist of an anguished story, borrowing the consciousness of a woman from another time, a victim’s consciousness, one that continues to loom large in the present.”

Of course, the plot and narrative are still the ultimate draw here, and they’re presented with a mastery of language that is at once aggressive and delicate. There’s a lyricism and a rhythm to the parables and myths told by the narrator, juxtaposed by her aggressive personal tone in such a way as to make the reader wince. This is narrative engagement rarely seen. The narrator’s emotional rawness runs perfectly parallel to the knowledge she imparts.

She speaks of Bese, the protagonist’s grandmother, and the nomadic journey she takes after being exiled from her homeland. She reminds the protagonist of her own journey, at the age of twenty-five, to her grandmother Bese’s village, long after the world has moved on, and the people she meets there.

She spends half the novel somewhat sporadically telling tales of Zulqarnayn, a conquering warrior leader who is thought to, in fact, be Alexander the Great. His exploits are recorded in the Quran – most famously, he erected a wall which separated the land of man with that of Gog and Magog, a tribe whose identity shifts in the telling, across Judaism, Islam, and Christianity.

In Every Fire You Tend, he narrator’s retelling of the bloody exploits of Zulqarnayn are exhilarating enough to have been a worthy short novel in their own right, told as they are with all the flair and pomp of a great Greek or Norse myth.

Likewise, our narrator recounts moments from the life of Hizir (or Khidr), an Islamic prophet, messenger, and angel. He appears throughout the story as both himself within his own tales, and as a kind of vision and reincarnation through the life and experiences of Bese, the narrator’s grandmother. Hizir and Zulqarnayn are described as ‘milk brothers’, born on the same day and with their lives overlapping time and again.

Yet the juxtaposition between the two is intensely fascinating; reading of their exploits and the philosophies they espouse (more through their actions than their words) is endlessly thought-provoking.

“Let’s leap out of this desolate time in which people aspire to perfection outside themselves, and into a time in which they attained perfection within.”

There is no straightforward narrative here in Every Fire You Tend. The book is an ocean, moving gently this way and that, with a sort of end in sight but no rigid plan for how to arrive there.

And yet, despite this parabolic and often dreamlike way of journeying across its pages, the novel never comes across as surreal or overwhelming. It’s manageable, engrossing, detailed, and encourages us to feel our way through as much as to watch or listen.

The book’s plot and narrative could perhaps be called abstract, even disorientating on occasion, but it holds the reader’s hand firmly enough. And the disorientation that it levels upon us is only in service of its goal to make us feel empathy for the lives and experiences of a now all but forgotten group of people who suffered great torment beyond what most of us can understand.

Conclusion

The night I finished this book, I had a nightmare. I was on an island with my partner; we had been invited there by someone we thought was friendly, and then abandoned as planes that we assumed were innocent began raining fire down on the island until, soon enough, we had nowhere left to hide.

That dream, I understood the next morning, was perhaps a result of the book’s ability to create empathy in the reader.

The guilt and helplessness that the protagonist feels, and the way that her narrator forces her to confront ugly truths, seeped into my mind and forced me to face my own naïveté. Every Fire You Tend had a profoundly personal effect on me as a reader. It leads us on an unforgettable journey through history, Islamic tales, and the very real lives of a very much forgotten community of innocent people. This is a novel for the ages.

Check out our review of Tilted Axis’ other 2019 hits: Of Strangers and Bees and Tokyo Ueno Station