Language is highly politicised, it can be used as a weapon, used against us — as we’ve seen time and again in our current political climate. The simple use of a certain language or dialect can also be a dangerous, rebellious, or illegal act the world over.

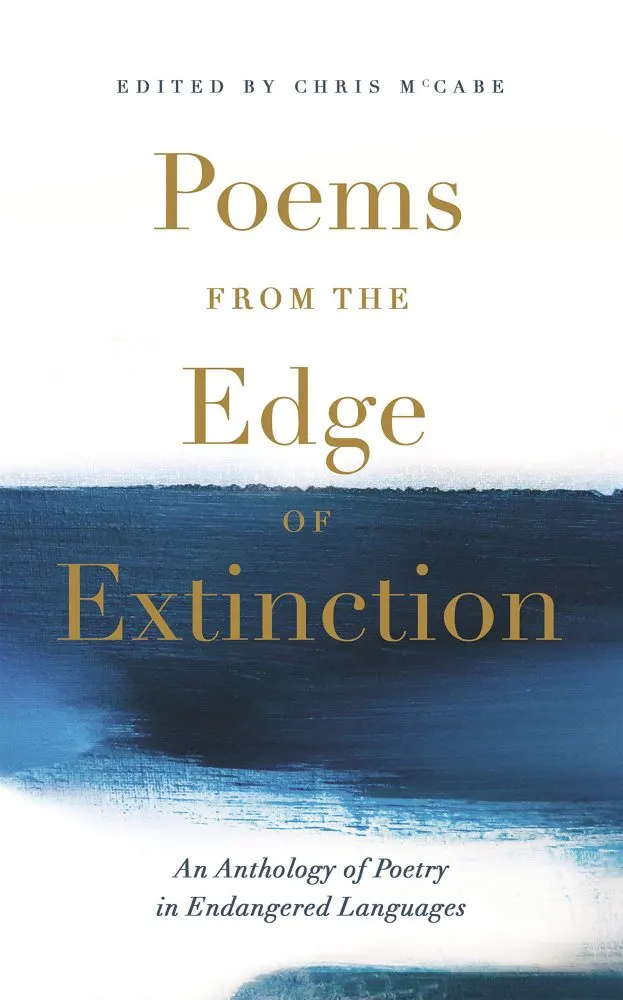

Both today and throughout history, people have died to preserve their culture, their language, their birthright. Language is a science and an art form, and every year thousands of those art forms come under the threat of extinction. This is what makes this new collection of Poems From the Edge of Extinction such an invaluable and powerful language capsule.

In this collection, gathered by Chris McCabe, we have been given a gift: the change to read and enjoy fifty poems from languages around the world that have been classified as endangered in 2019 (as identified by UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger).

These are fifty artists who “defy, distort and transform their everyday language into the acts against-extinction that run through these pages”. It’s an incredible journey that takes the reader deep into the woods of our global history, the history we should know, our shared commonalities, and our rich and beautiful linguistic diversity. It’s a celebration of “the fundamental role verbal art plays in human life around the world”.

The preservation of endangered languages is something I have personal experience with as a Welsh national. Welsh, by the way, is one of the languages featured in the Poems From the Edge of Extinction collection, along with several other languages close to home – Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic, Cornish, and Faroese).

Only a single generation ago, Welsh was on the verge of dying out: dropping to 18.5 percent of the population in 1991. As the New York Times reported: “Welsh went into rapid decline in Victorian times, when schoolmasters bent on Anglicising the Welsh beat the language out of the country, often literally”.

One harrowing anecdote reported in The Times explained: “In some Welsh schools in the 19th century, any child who was heard speaking Welsh was made to carry a small piece of wood, which they passed to the next child thus overheard. Whoever was left holding this badge of shame (known as a Welsh Not) at the end of the lesson was severely punished.”

Measures were quickly put into place. In the year 2000, when schools implemented compulsory Welsh lessons up until the age of sixteen, bilingual signs and announcements also became part of the Welsh government’s plans to get one million people speaking Welsh by 2050.

How different the story could have been considering “about 3,500 languages – half of the 7,000 languages spoken today – linguists estimate will fall silent by the end of this century.” – Mandana Seyfeddinipur

This story is far from unique in Wales. China might technically have one unified language now (Mandarin – based on the dialect of Beijing), but in fact it has always been a collection of disparate languages, roughly divided by provincial borders.

In recent years, these local languages have come back into popularity through mandatory lessons in schools, much in the same way that Welsh has. But the same cannot be said for most endangered languages across the world. And so we must thank Chris McCabe for collecting these incredibly valuable poems.

Poems From the Edge of Extinction

We were lucky enough to do more than just purchase this book. We were also able to be audience to an event at the Southbank Literary Festival. For the event, Chris McCabe gathered several poets and translators, all featured in Poems From the Edge of Extinction, and invited us to enjoy an evening of their poems in their original languages and in translation. One such poet was Nineb Lamassu.

Nineb Lamassu is an Assyrian-Iraqi poet who writes in the endangered language of Assyrian, a language spoken predominantly in Iraq and Iran (and is purportedly the language spoken by Jesus Christ).

On his language, Lamassu states: “it keeps me alive and I keep it alive.” His poetry has been translated into a number of languages, including English Turkish, Kurdish Arabic, Spanish and Swedish. He’s a UK citizen but has recently returned to Iraq to work as a peace-building advisor for INGO.

In Choking Smoke, Lamassu writes a harrowing account of his home country of Iraq:

“My country

Is a beautiful young woman

Enchanting you simply by her sight

And then disappeared of a sudden

& you search in vain for her in the slaughterhouse”

Choking Smoke, translated by Stephen Watts

Speaking of the 1913 genocide, Lamassu explains that men traditionally take the mother’s name in his culture since most of the men/fathers were lost to the genocide, “although I like to see empowerment in that” he states. “We as poets need to be a voice for the voiceless”. – Lamassu poignantly dedicates his poem to those protestors who are risking their lives daily, especially those who are detained.

This was a poignant thought as we moved on to the Rohyinga language, a language silenced within its own home state of Myanmar. 650,000 Rohingya were forced over the border into Bangladesh in 2017 and continue to be persecuted to this day.

In Bangladesh they live in refugee camps that today resemble shanty towns and even cities. I Am a Rohingya – written with James Byrne, a poet, editor and translator, and co-edited by Shehzar Doja, poet and founder of The Luxembourg Review – is officially the first anthology of Rohingya poetry in the West and has been described by Forrest gander as ‘gulping firewater shots of the world.’‘

Rohingya poets have to pretend they’re someone else if they want education, Shezar Doja tells us, a basic human right. It’s a powerful moment as he explains that you’ll find that most Rohingya poetry is written by poets using a pseudonym for their own protection against further persecution.

The poets in the collection are trying to preserve their own language and identity in the face of genocide – it’s a language that’s in danger of being systematically wiped out.

Vaughan Rapatahana, who is published in both his main languages, Te Reo (Maori) and English, is a Kiwi poet who spends half his life in Hong Kong. His poetry blends Maori, English, and Cantonese languages poignantly and beautifully.

Onstage, Rapatahana tells us of the Te Awa Tuapa river in New Zealand, sacred in the Maori culture. Recently, a historic law was passed in New Zealand, giving the river protected status. He argues that language, likewise, is just as imperative to our lasting culture: “language needs to be sanctified”.

In his powerful poem, he talks of colonisers, of the past, and of the continued arrogance of those English speakers who make no efforts to speak the languages of the countries they visit, live in and eventually colonise.

Valzhyna Mort, the final speaker of the evening, is the author of two poetry collections: Factory of Tears and Collected Body. She writes in English and her native Belarusian, and lived in the US where she works as a poet and professor.

During her time with us, Mort recounts a harrowing moment in Belarusian history: the night of the murdered poets in 1937 where 130 Belarusian poets were murdered by order of Stalin, and over 1000 manuscripts were burnt. She talks of the mass graves of the Soviet era that are still unacknowledged by the government: the history pages are blank.

It’s a bleak and harsh reminder of how the victors write the history books and how easily a culture can be wiped out. We’re reminded of how powerful words are and why those who write them are often the first to go when under the fist of an authoritarian regime. “Tongues were removed; we talked with our eyes”.

This evening of poetry and storytelling from poets of endangered languages was a powerful and vital introduction to reading the poems we walked out with, and we hope this will prove as valuable an insight for you as well when you, too, read Poems From the Edge of Extinction.

Thank you to The Southbank Centre for our tickets to this event.