We are often told the right ways to love and be loved: what our expectations of love should be and how we ourselves should behave in love. We can predict a good marriage, and should expect one, too.

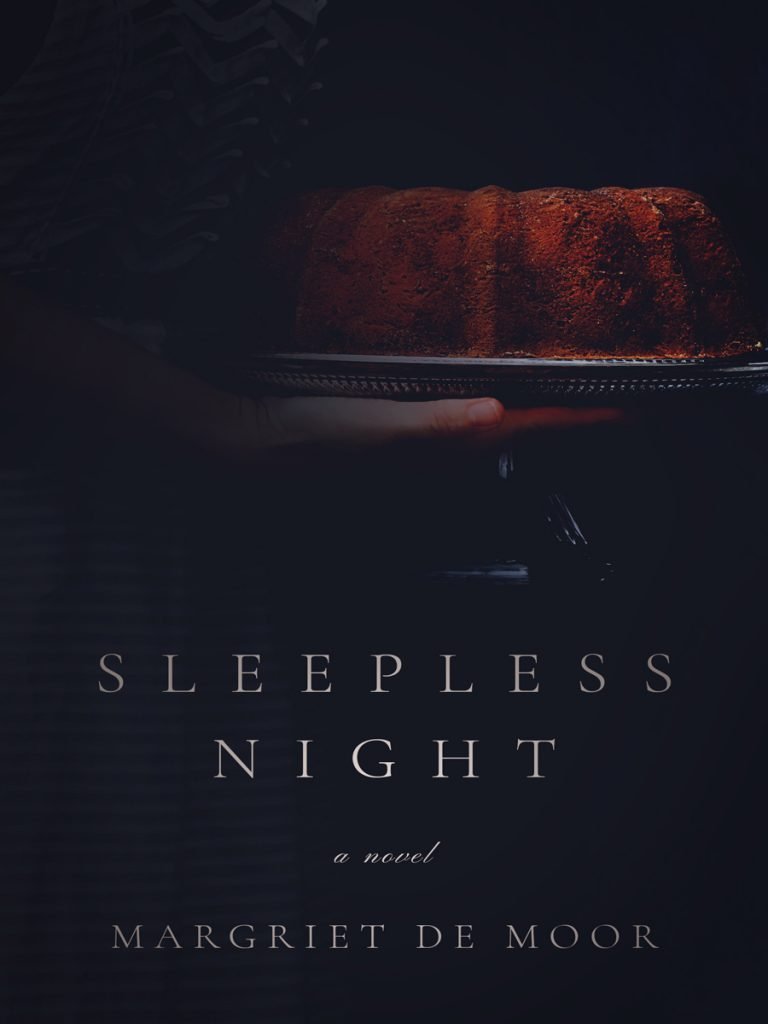

We know what a friend should rightly be called on to do in the name of trust and kindness. But all of these things can be disrupted, found to be lies, and may be called into question at any moment. In Sleepless Night, Dutch author Margriet de Moor does just that.

“The night is at its coldest now. I do not need a clock to tell me how deep the darkness is. I can hear it in the cold.”

Margriet de Moor herself has lived a fascinating life, celebrated dearly in her home country of The Netherlands. However, she did initially study – and later teach – classical piano. Before becoming a household name as an author, her life was dedicated to music.

Now in her later years, she is, at last, making a name for herself internationally. This is partly due – at least in the case of Sleepless Night – to the careful and precise translation of David Doherty.

Trust Has Issues

“As I turned away from my late husband’s face, impervious now to tears or laughter … it occurred to me for the first time that there was no note. My husband had shaken off this existence, including our time together, without a word. A private matter, that was all it had ever been.”

Sleepless Night is told through a successful framing device: our nameless protagonist often finds herself troubled into restless insomnia and so, when this occurs, she pops into the kitchen and spends the rest of the dark night baking.

Tonight, it’s a Bundt cake. As she bakes, she recalls her recent dates and sexual adventures as a widow, and the short marriage she lived through with her husband Ton at the turn of the ‘70s – a marriage which lasted only fourteen months before Ton took his own life. Ton left no note; the suicide was done in his greenhouse on an innocuous day with no apparent triggering.

The mystery of his suicide is what drives the story for the majority of this slender little book, which can be easily read in a single sitting. And perhaps it’s best that you do – that you help carry that momentum until the end. What this affecting story leaves us with, upon its closure, is the nervous unease that life doesn’t care about us. That there is a deeply felt unfairness with regards to our own plans versus the chaotic randomness of the universe.

That we may never truly know one another as much as we’d like to, or as much as we think we do. A feeling of loneliness pervades in a big and very successful way. If you cannot plan or predict your life, and you can’t ever fully rely on those closest to you, then you are truly, frightfully alone.

This isolation is reflected in the cold aloofness of our character. She goes on dates years after losing her husband – she treats the bodies of these men as playthings and has grown so stoic that she frequently looks back at her brief life with her husband and ponders on whether he ever loved her.

More than that, in fact: on whether she ever loved him. Trusting in her own heart has become a complex endeavour.

“Months of wet weather must have followed. For, thinking back, there was always rain in the comments that the outside world inflicted on me and the various forms of obsession that brought me comfort.”

As the story progresses, the driving force is the question of why Ton put the gun to his head. Almost teasingly, we are drawn through a labyrinth of time: from memory to memory to present day, with no distinguishing lines between them.

Allow your mind to wander for a moment, as you read, and you’ll no longer be sure which era she is now recalling. And so, the question of why seems to be whisked away over and again as we are dragged through the dirt of her sombre reminiscences.

While this is at once compelling – our linear lives often feel, ironically, far less than linear – it does cause the final few pages of the book to fall flat, as revelations go. Or perhaps revelation is too grandiose a word. After all, the ‘slice of life’ theme of this book is apparent, and so firmly opposes words like a revelation.

Life does not follow any hero’s journey. To tell the truth about the disruptions and disappointments of life is to abandon revelation, exposition, build-up, climax. This is, however, a novel, and as such we do expect more than just a start and a finish: we crave a beginning and an end.

Conclusion

There is, perhaps, no right or wrong in the debate between the accurate reflections of life and ideal narrative structures, but it does simply mean that taste will play a large role in determining your mileage with this story.

In Sleepless Night, we have a novel that can be seen as a feminist spin on the widow’s tale: a woman who feels less, but not nothing. A woman left with unanswered questions, but who must go on living regardless. A woman who can no longer trust this word and her feelings of love. She tells us honestly that love is unknowable and complex, as are people. Especially the people we love, because here again is love, complicating things as it does.

If you like this then you might like Happening by Annie Ernaux or The Devil Comes to Town by Paulo Maurensig.