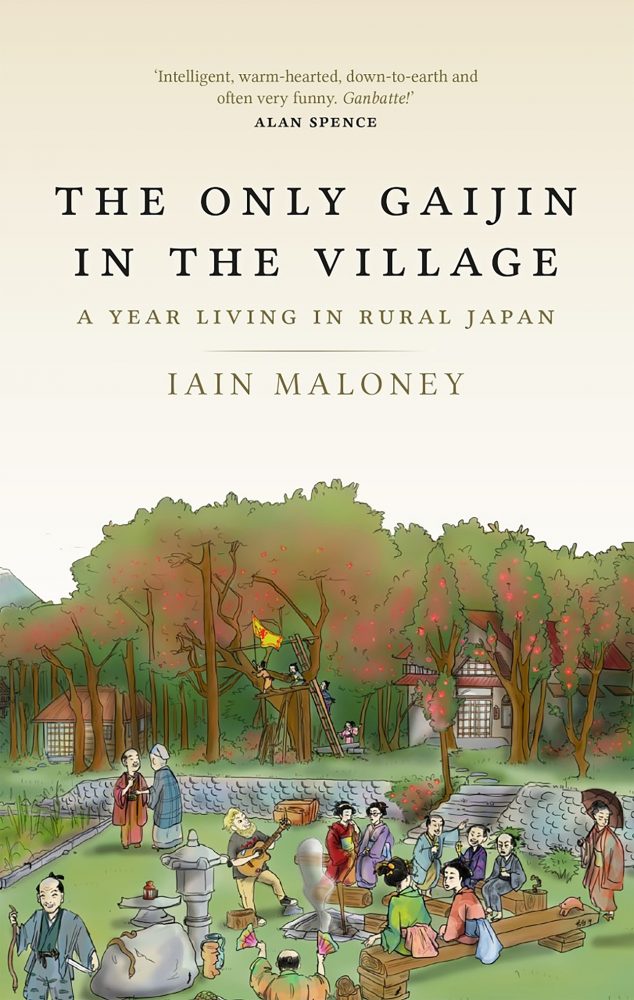

How do I know if my story is worth writing? This is a question I imagine must often pop into the minds of writers considering a memoir, be it about their career, their travels, or anything at all. What makes me stand out? What makes my story interesting? Well, as the only gaijin in the village, Iain Maloney immediately provides us with a hook worth pursuing.

Of course, Maloney is far from the only gaijin in Japan to live in a small village of locals. But, to my knowledge, he is the only one to write about this rather unique experience, and what really sells us on the subject is his witty and cynical personality.

That’s what, ultimately, carries every kind of memoir. If you’re not charmed by the writer, in one way or another, why would you want to spend 200+ pages with them? Well, it’s been a long, long time since I read a book where I felt as charmed by a narrator as I did by Iain Maloney.

As the title suggests, Iain is the only gaijin in the village: a native Scot who moved to Japan back in 2005, found love, built a life, and eventually decided to move out into the countryside, since both he and his wife grew up rural in their respective countries and were itching for a return to green hills and wide views of the horizon.

This memoir succeeds in part thanks to Iain’s aforementioned charms (more on that in a bit) but also because of his approach to storytelling. The Only Gaijin in the Village is divided up by seasons, and each of these seasons begins with a story of life in his little village.

These stories paint a vivid picture of the place and the people who populate it. Delightful characters who present Iain with technical and social challenges he has never had to face before, despite more than a decade in Japan and a mastery of the language.

Read More: Books to Read Before Visiting Japan

Village life, however, only takes up so much room in the book. The genius of Iain’s storytelling is how his chapters connect. The book is less a coherent narrative and more a naturally shifting and growing conversation between him and us.

It’s easy to imagine this less as a reading experience and more an imagined chat down the pub. You grab a pint, sit with Iain, and listen intently as he paints you a picture of life in the village.

This leads us to a point about his early days in Japan, a funny anecdote about his wife, or that year they spent back in Edinburgh. Which brings Iain to an interesting fact about the history of Scots in Japan. Speaking of Scots, there was this football match in Yokohama… And so, it goes.

This organic method of storytelling almost makes The Only Gaijin in the Village a hard book to define. It’s certainly a personal memoir, but it’s also a book that might enlighten us about aspects of Japanese tradition, history, language, and politics that we had never even considered until now (like how the English phrase ‘head honcho’ comes from the title ‘hanchō-san’. Mind blown).

And all of this only comes about because the narrative of the book so delightfully twists and winds its way through various topics arrived at only thanks to a detour two chapters back.

Much of what the book covers certainly is personal. We spend our time dancing between Iain’s present life in his new village in Gifu and his past: Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Nagoya, and the people he has met, loved, and hated along the way. The personal connection goes beyond stories, however.

To return to the pub metaphor, Iain does what we all do when meeting a new person: insert a few hesitant comments about politics early on. Then, when you’re settled in and you know that the other person is sticking around, you start to rant a little.

Your politics and opinions become unsheathed completely and the rage rises to the top. What begins as a clear-cut narrative about life in a Japanese village is soon peppered with hilarious digs at the Daily Mail and Donald Trump.

By the halfway point we have sentences ending with something along the lines of, “…and that’s what’s so fucked about capitalism.” And I am with Iain all the way, laughing, nodding, and sharing in his grief.

Read More: Japanese Literature: Where to Start

The British (and, more specifically, Scottish) wit and charm is also dialled up to eleven from beginning to end. So many metaphors in this book make reference to politicians, celebrities, and human stereotypes. And then there are the obscure references that had me giggling like a child; one in particular being a reference to my favourite Eddie Izzard bit about a canteen on the Death Star (you’ll need a tray).

It felt like that was put in only for Maloney’s own amusement and here I am creased up by not only the memory of the bit but also the fact that Maloney clearly couldn’t resist slotting it in for the sake of fun. This is the personality that carries the narrative. It’s the personality that lights up all the wild facts and strange anecdotes.

There is so much enjoyable cheek and cynicism in this book; so much so that you’ll need to pay attention to your own face as you read, and there you’ll notice how you spend half your time chuckling and the other half frowning at the injustices and absurdities of the world.

Towards the end of The Only Gaijin in the Village, Maloney bemoans the tired genre of my-first-year-in-Japan stories. This leads to a full rant that I greedily ate up, nodding in agreement the whole way.

The rant concerns fellow gaijin who prattle on about how they never fully fit in with Japanese society, how they always feel like an outsider, how this is somehow a grave injustice.

And to this, Iain sighs and says, though not in such simple words as I’m using here, “well, so what?” He points out that he always felt like an outsider in Scotland and that, at least in Japan, it makes sense. His wife, too, is treated as an outsider in the village. Anyone would. It’s normal.

Here, Maloney picks apart the racism that’s bundled up with tired and typical gaijin complaints, and it is so refreshing to read.

Conclusion

I loved every word that Maloney had to write about his life, about his village, his wife, his childhood in Scotland, his work, his friends, all of it. I loved it because it was told with so much love and wit and charm.

There is no bemoaning his lot in life in The Only Gaijin in the Village; instead, there’s confusion and frustration and rolling with it as things start to make sense. Here is a tired and cynical lefty, angry at the world, telling us the story of how he decided to build a life in a small Japanese village with his wonderful wife.

Maloney fills his story up with little-known facts, anecdotes about Japanese tradition and language, and musings on politics and people. You’ll laugh and cringe and sigh along with every story and, when you start to miss Maloney’s charms, you’ll open the book and do it all again.