What do we picture when we’re asked to think about refugees? Most of us, I’d wager, see exactly what the author of one of the stories in this book, The Dancer’s Tale, pictures: “Harrowing images of women and babies on sinking boats … a tattered, angry mass at the Jungle in Calais; children behind barbed wire fences; clamouring groups in tented cities.”

When I read this I thought, yes, that is the image that defines a refugee for me. Like most of you, I harbour a great resentment towards my government, and other governments, for their dehumanisation, dismissal, and disregard for refugees.

And while Refugee Tales III often tells me that I’m right to feel this way, it also does a lot more than that: it shows me the faces, lives, and stories of these refugees. Because it’s all well and good for those of us who wish to help refugees to say, ‘These are people just like you and me! We can all become refugees! We are all human!’ but do we actually know the lives of these people?

I’m not saying that we shouldn’t defend and support them, but we should also know them. Reading Refugee Tales III is how we start to do that.

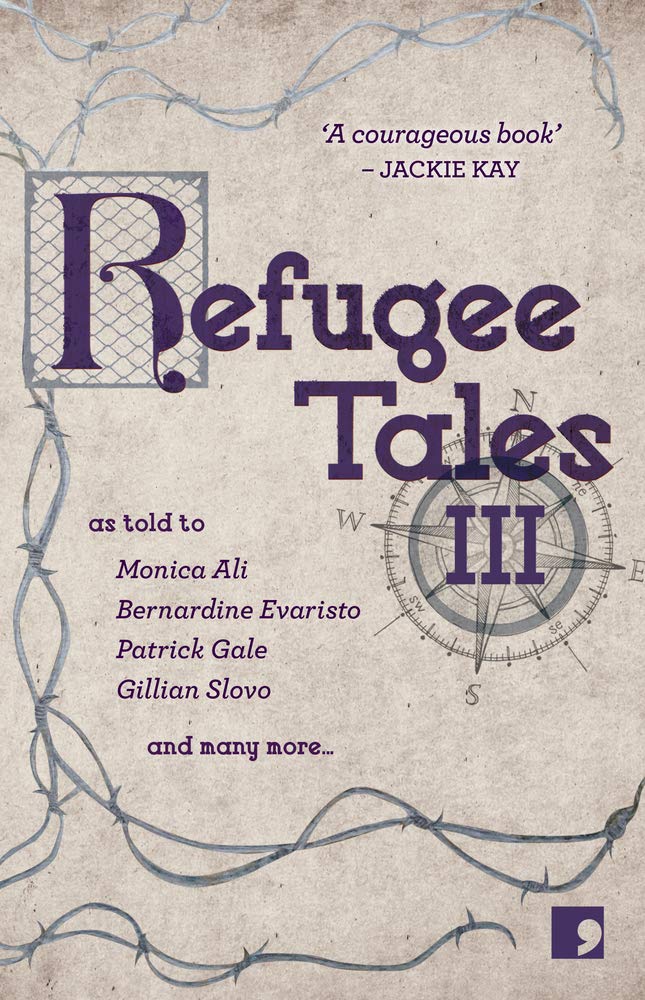

Comma Press is one of the publishers that we cherish the most. Their ‘A City in Short Fiction’ series’, which document literature from cities all across the globe, capture the essence of a place and give those of us who can’t see these cities for ourselves the chance to understand them through their stories.

Books like The Book of Tehran and The Book of Cairo have injected our hearts with a newfound love for these places, their people, and their art. Extending this love even further, Comma Press are helping to give voices to the voiceless through their Refugee Tales books.

To learn, through first-hand accounts, about the Kafkaesque bureaucracy, the cruel and sadistic emotional torture, the flippant disregard that the British government and its systems have for refugees and asylum seekers – regardless of who they are, where they are from, and why they are here, is stomach-churning.

Of course, we already know the suffering that refugees go through, but to read about the intricacies of this suffering, and the real lives of the real people who must be subject to it, brings it home in a visceral and necessary way.

“Cruelty is the currency he lives by. The world he has by chance been caught up in is a frightening place … These days the rich and powerful bottle inhumanity and sell it to the displaced. And underneath this poisonous air, rage and helplessness thrive in equal parts.

It’s the breadth of difference that’s most striking here. Refugee Tales III is a reminder of just how different each of us are. Some of us are parents, some of us are divorced, some of us have lost loved-ones; we have different jobs, educational backgrounds, religions, beliefs. I could go on. But it’s easy to overlook the fact that all of this goes for refugees, too.

This breadth of difference is highlighted most simply in the Chaucer-esque titling of these stories: The Teacher’s Tale, The Father’s Tale, The Applicant’s Tale, The Stateless Person’s Tale. I was struck several times by the very idea alone that some of these refugees are professional dancers, care workers, father’s without sons, orphans, fishermen. They’re anyone and everyone, because they’re people.

They are all people who have survived displacement, run from murderers, lost their homes and their families, and are now subject to the cruel and uncaring anonymous systems that keep them suspended in an invisible net of ambiguity and uncertainty. Take, for example, the book’s very first story: The Stateless Person’s Tale.

This man recounts his twelve years as a non-citizen of the UK, how he arrived, and how he has existed – not really lived – ever since arriving.

He is not able to legally work, to become a part of the country, to do his part, as he desires. He is in danger of deportation constantly. His life is defined by visits to various offices that could go any of a number of ways, some good, mostly bad.

He has been driven to depression, a few steps from madness, and he finishes his tale by saying, “If they turn me down this time, I’ll pack my bag and go to the Home Office and tell them to send me where I want, even if it is only to dump me in the middle of the ocean.”

“Refugees are a municipality of individuals, ordinary and extraordinary, wrenched by circumstance from homes that have become uninhabitable, tossed about in the endless paperwork that nation states engender.”

A later story, The Fisherman’s Tale recounts in detail the journey a refugee has taken. He is a farmer from an anonymous nation, of a religion nobody has heard of, run out of his village by ISIS. He is a man of peace, innocence; he is harmless, and he wishes only to be treated as a human. His journey takes him across Europe to Norway, where he and others are kept by the government in an army building.

He recalls his journey and his treatment in short bursts of abrupt sentences. His anger and confusion can be felt palpably. He does not understand the flippancy and the unkindness he has been met with, when he is nothing more or less than a victim.

Conclusion

The stories in Refugee Tales III expose the sinister heart of the systems built for refugees in the UK. Or, perhaps worse than that, the cold, callous ambivalence of the system; one that’s designed like a labyrinth or a rollercoaster that ends with a drop into the ocean.

The worst thing about this ambivalence is how it spreads and infects the British everyman. I was, a few years ago, driving past the Jungle in Calais with a loved-one; I made a comment about how empty and cold its existence made me feel and he flippantly responded with, “Aye but it’s gotta be there.”

I’ve spent years trying to understand the mindset that led to his response and, unfortunately, attitudes like this one are built by the rhetoric spewed out by our government and our tabloids. But to people who share this cold and uncaring – perhaps even resentful – attitude, I ask you to know these people. Read their stories.

The tales told in this book have the power to humanise better than any news reports or cold numbers. These are real accounts of real people who happened to have lost their homes and have been unjustly punished for being victims. If anything is required reading in 2019, it’s this book.

If you want to read more important works published by Comma Press, check out:

The Book of Cairo, Thirteen Months of Sunrise, and The Book of Tehran