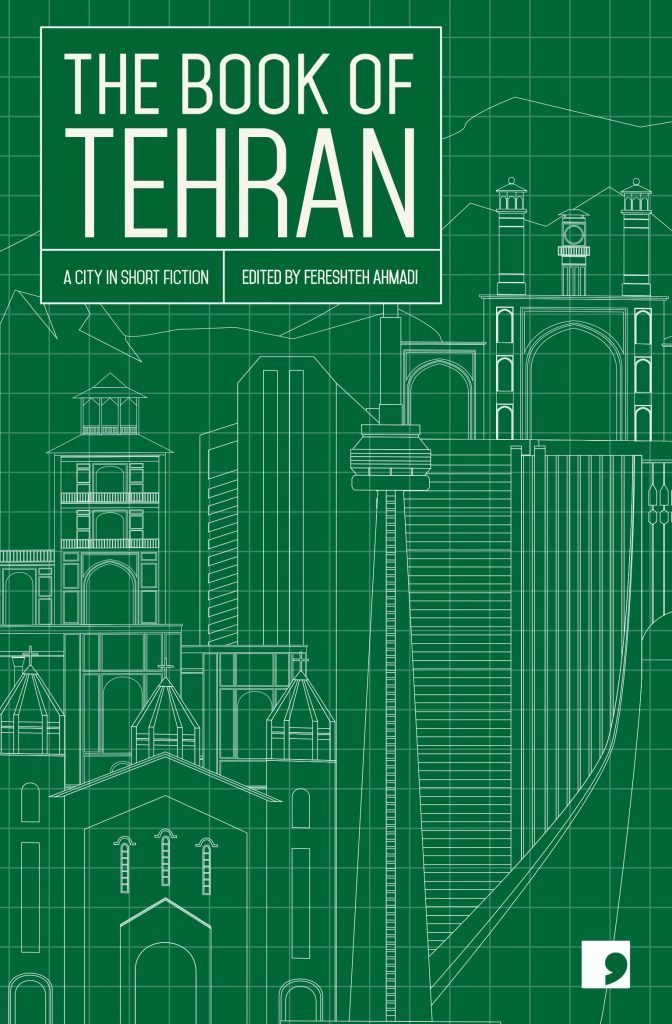

Here is the latest in Comma Press’ fantastic vision of gathering short stories from cities all around the globe, translating them, and binding them together in beautiful collections, dubbed A City in Short Fiction. Following the massive success of such collections as The Book of Tokyo, The Book of Gaza, and The Book of Istanbul, we are now gifted with the eye-opening The Book of Tehran.

Reading the City

Before we get into the meat of these tales, I want to stress the importance of the generosity on display from Comma Press. This publisher has had the vision to collect tales from every corner of the world – from writers large and small – and bring them to you, translated with heart, bound with beauty, and placed in your hands with a view to entertain, enlighten, and educated the reader on the beauty and variety of storytelling that our pale blue dot offers.

“I am superstitious and, if you were to ask me, I would say there is a correlation between superstition and selfishness.”

It cannot be overstated just what a treasure each and every one of these short fiction books is. Any culture you wish to know more about can be accessed now through honest and thought-provoking literature.

As a writer whose entire hope with what he does is to inspire people to learn about cultures beyond their own borders, to be encouraged to travel, to understand the world better, to reduce xenophobia, and to inspire wonder and awe, I cannot thank Comma Press enough for what they do here with these books. They mean more to me than I can say.

Who is Tehran?

So, here we have a collection of ten stories by ten Iranian authors, translated into English by ten different translators. It’s an incredible undertaking that paints a vivid and tangible image of the city of Tehran.

The stories themselves are hit-and-miss in their impact, with some leaving the reader shaken and disturbed, and others failing to leave any concrete impression – this is more often than not due to the writer’s style and approach than it is anything to do with cultural distance.

For example, the book’s opening story, Wake It Up, is an infinitely clever and subtly disturbing tale about a writer who believes that good art can only come from tragedy, and so, when his girlfriend leaves him, he hopes to be inspired.

But the tragedy that finds him is not the kind that shocks but the kind that leaves you deflated and blubbering. It’s a masterfully impactful tale. In contrast, the book’s seventh story, Circling that Heavily-Burdened Tale, was a story I found impenetrable in its stylised storytelling; I was unable to follow its events and connect with its characters.

“You watch the scene unfold in bewilderment from your dark corner and your voice gets lost in the back of your throat … you are suddenly faced with a much more painful ending to your night than just a bout of sleeplessness at 3:36 in the morning.”

What this book does so well, however, with its hits and its misses, it paints a surprisingly coherent and solid picture of Tehran. Almost every story has at its heart a feeling of paranoia, doubt, suspiciousness, and voyeurism.

The characters in these tales have an obsession with being seen and recognised – whether they are seeking attention or attempting to avoid it – and many of them question their own identity or that of their friends and neighbours. There is a fear of the truth coming out or the truth being hidden.

It becomes clear, the deeper you dig into these tales, that this fiction is indicative of the attitudes of the city they represent: Tehran is a town of insecurity that feels at times like a Frankenstein’s Monster of negative feelings and shaky foundations.

These writers’ ability to transfer that difficult-to-catch feeling and convey it so clearly on the page is utterly masterful, and it is an ability shared by all of them, whether their story is good or bad; whether you like it or not. The Neighbour, the book’s eighth tale, captures this mood perfectly in a handful of pages, as a young woman is accidentally locked out of her apartment and invited in by her neighbour.

There is a wordless dance at play between them, as she attempts to understand her neighbour based on her appearance, and what might be hidden between her words or how she says them. Paranoia and insecurity are rife in this story, epitomising this feeling of doubt and voyeurism.

The story which left me most shaken, a story which I found myself rereading because I was hungry for the feeling it left me with, was Domestic Monsters, a kind of letter from a young girl to her aunt which begins with the girl regaling her aunt – and, by extension, the reader – with stories from her childhood, as her aunt poked away at the girl’s notions of what kind of person her mother – the aunt’s younger sister – really was.

At first, she says she is grateful to her aunt for exposing her cruel and beastly mother, but as the letter continues, its tone shifts and the manipulation at play becomes exposed like a skeleton in the closet. It plays out like a political drama, all in the form of a letter laced with passive aggression and frustration. It’s a masterful piece of writing.

“That night I took a big step. And like a caring mother, you laboured hard for my hatred to be born. I dug and ploughed and little by little, hatred replaced my dependency on my mother.”

Conclusion

There is a truth, honesty, and earnestness to these illuminating tales. They are each varied and distinct from one another in their characters and events, but they all share a common tonal thread of paranoia, insecurity, and judgement that illuminates the darker corners of Tehran.

From the man who wakes up to find a stranger in a white suit sitting alone on his sofa, illuminated by the light from the kitchen, to a story about two young actors paranoid about being watched and so acting as though they are, there is a feeling which lasts through The Book of Tehran: the feeling of a cold hand on your shoulder that probably isn’t there at all.

If you liked this review then you might like: Broken Stars – A Chinese Sci-fi Collection