When it comes to adaptation, book-lovers often feel divided. Some welcome film adaptations; others don’t see the point. Some spend hours debating which is better. I am of the opinion that a book and a film are too far apart to be compared clearly and fairly.

But graphic adaptations exist in the gap between literature and film, and so can often work as a perfect means of adapting a piece of written work into something more visual, while retaining much of the writing that made it special.

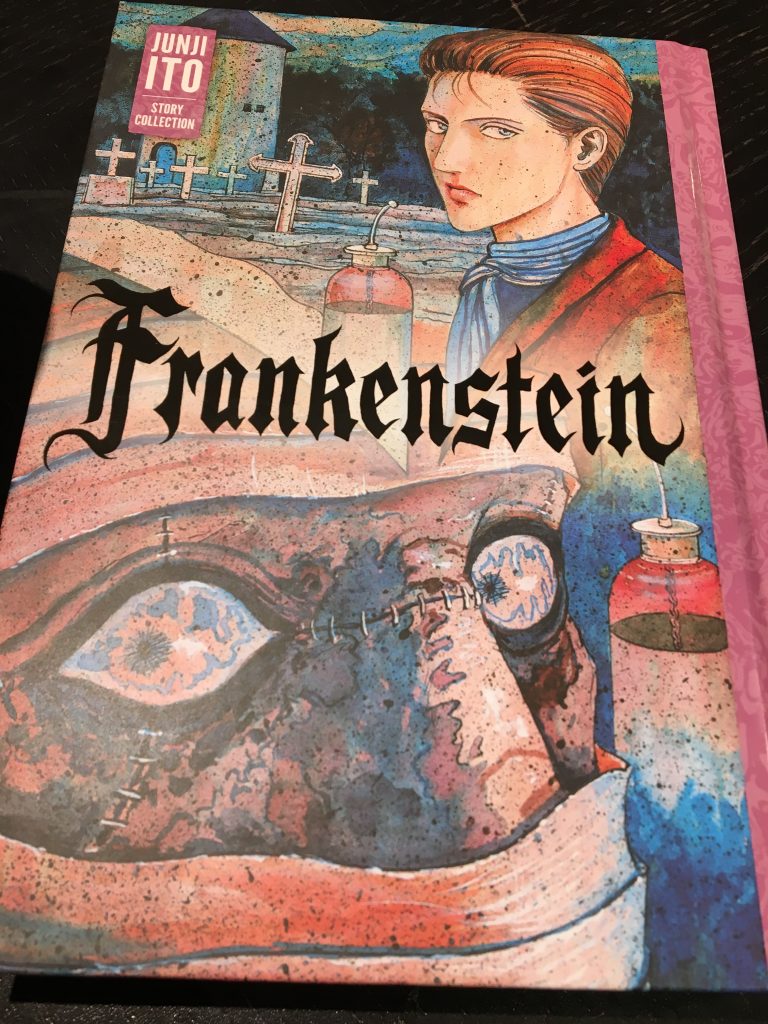

With that cleared up, there is arguably no greater pairing than the works of Mary Shelley and the aesthetic style of Japanese horror manga legend, Junji Ito.

How to Adapt Frankenstein

One of the many things that makes Frankenstein such a timeless and important work of literature is Shelley’s writing. She had a particularly fine vocabulary, and the confidence to use it with ludicrous dramatic flair.

One of the intrinsic themes of gothic literature something called The Sublime (in caps for dramatic effect). In a nutshell, the sublime is an aesthetic fixation on the overwhelming power of nature over the human mind and heart (sunsets, mountain ranges, storm clouds etc).

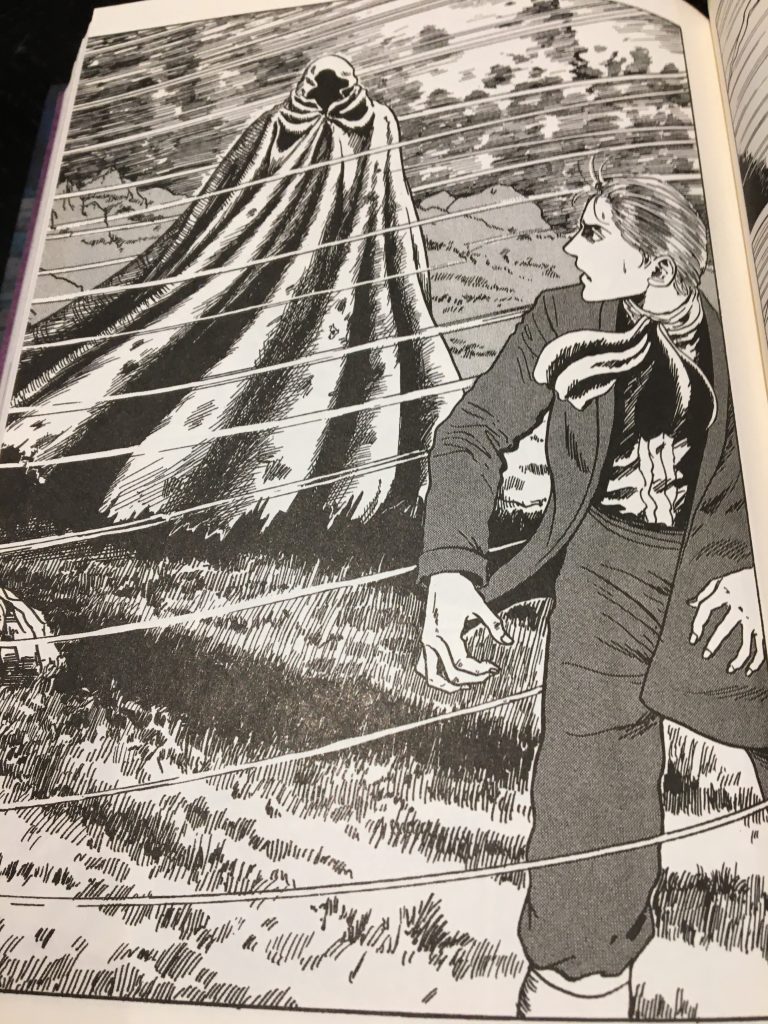

Shelley wrote about the sublime better than anyone, with astonishing strength of effect. And Ito is able to confidently convey Shelley’s effect here with his art.

By taking Shelley’s dialogue and placing it over some of the most beautiful pencil drawings of cliffs, forests, mountains, snow, lightning, and rain that I’ve ever seen, Ito has sacrificed not an ounce of Shelley’s impact in translating Frankenstein into a graphic form.

I should say very clearly that, if you have never read Frankenstein before, this is the best short adaptation you’ll ever find. There is now no reason whatsoever to touch any of the shoddy film adaptations (especially the one by Kenneth Branagh) now that we have this.

The actual story of Frankenstein is almost completely maintained in the book. The characters behave as we know them, and the pacing and events all remain faithfully intact. The only artistic licence Ito takes comes later in the story, as Frankenstein is building the monster his bride. This scene plays out very differently from the original (Branagh also decided to radically change this scene, as well.

What’s everyone’s problem with this part of the book, exactly?) I won’t spoil how Ito changes it, of course, but I have to admit that I liked it. As the one change he makes to the story, it does nothing to harm the original.

In my reading, I was astonished time and again by the love and attention that Ito has put into his work here. His stories and art have always been of an astonishingly high quality, but here we see not only his love for her craft, but also his respect for Shelley’s novel.

Ito clearly adores Frankenstein; and here he has given us at last the visual adaptation that the world has been clamouring for.

Read More: 11 Best Junji Ito Manga

More Original Ito

The other great gift that Ito gives us here is an original series of tales which span the whole second half of the book. Frankenstein itself only fills the first 180 pages; the rest is an original collection of six fantastic short tales, all centring around a young Japanese high school boy named Oshikiri.

I really do not want to spoil much of Oshikiri here – in fact, even the blurb does more spoiling than I’d like it to, so I would advise avoiding even that – but I can safely say this much: Oshikiri is a fairly meek, borderline bland boy who lives in a small town.

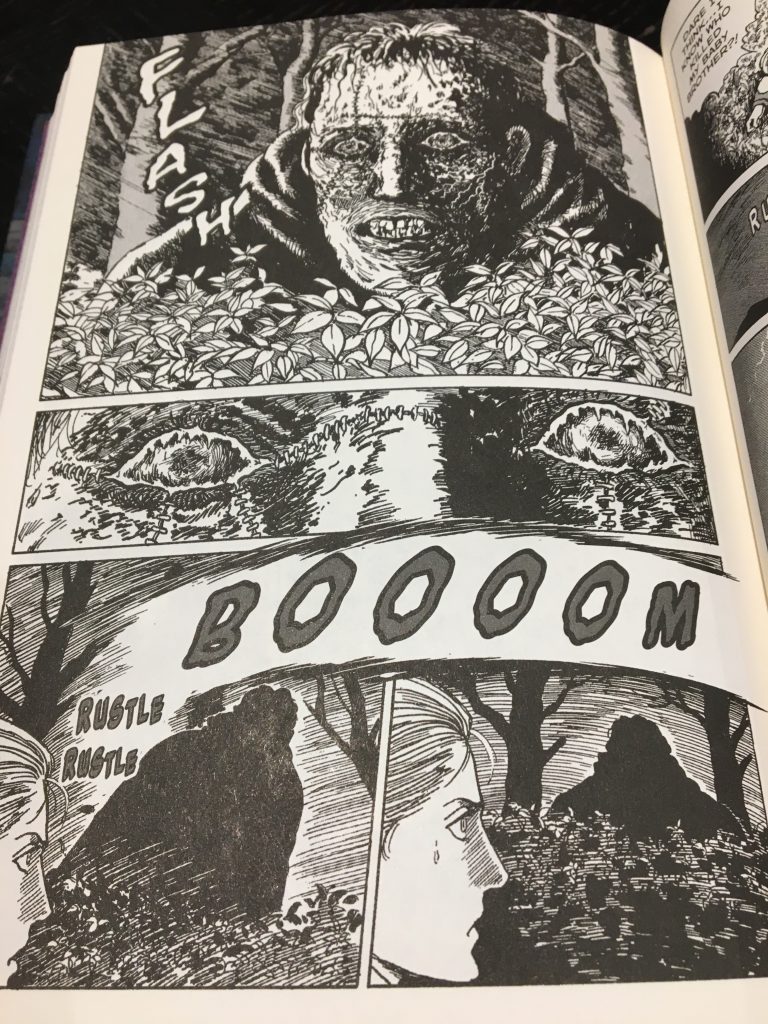

These six stories are all from his perspective, and the way in which they actually work together is part of what makes them such tiny masterpieces of terror. The first story, only thirty-odd pages, carries such an impact that it is difficult to understand how the others will follow it.

And, indeed, as you start the second story you might wonder how this can even be the same boy and the same story, but all is made clear as you read on (again, the blurb actually spoils this mystery, so avoid it). I am sorry that I can say no more about Oshikiri’s stories, but they are absolutely affecting and chilling slices of true heart-stopping horror and prickling terror.

Each tale approaches horror in a slightly different way: some are gruesome and disgusting; others are subtly creepy and unsettling. All are terrifying in Ito’s very own special way.

Conclusion

Junji Ito is Japan’s master of aesthetic horror. His stories are wholly his own, and the frightening power that they have is greater than that of most of the world’s most successful horror writers.

Ito has managed to disturb and shock me with greater effect than any horror writer I’ve ever read, and he deserves to be better known across the globe. Maybe this adaptation, created with real heart and soul, will be the thing to make him more of a household name. I certainly hope so; it’s bloody perfect.