In the heart of the city there are so many lights. The streets are lit up and the people can see themselves and one another with clarity; there’s nowhere to hide. Close by there is the sea: endless, dark, unknowable. Between the two, in a nameless place, live a father and son.

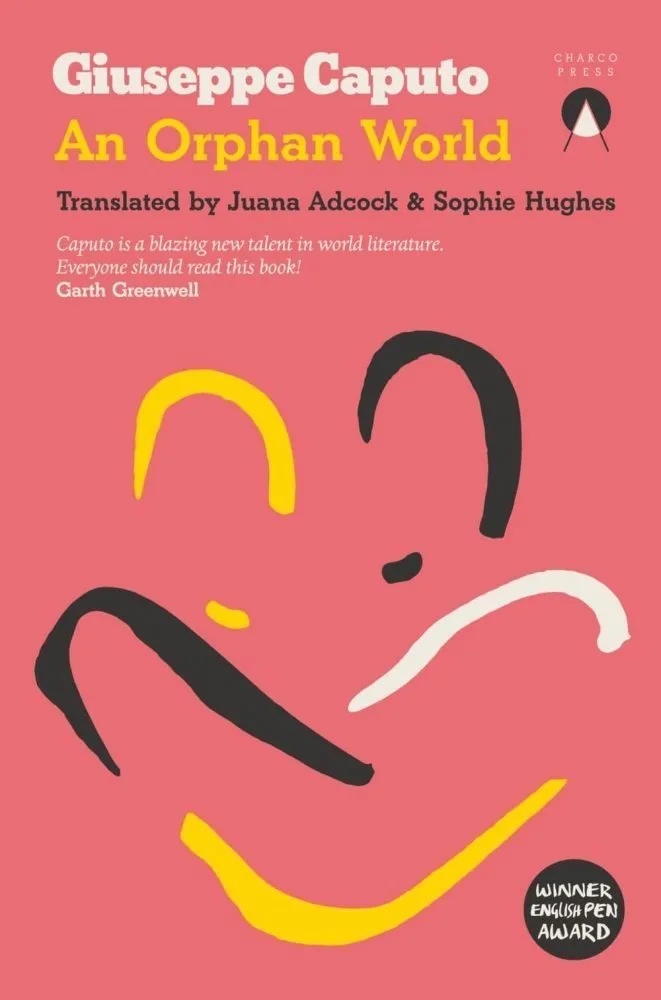

They have no money, but they have a roof – they live very much on the edge between where you can find everything and where you can find nothing. These are the protagonists of An Orphan World; Giuseppe Caputo’s brutal, bloody, starkly honest novel about the forgotten, invisible people at the edges of things.

An Orphan World begins in two places. One is a part of the past, where our protagonist draws us a picture of his optimistic but penniless father: a man who scrawls on the walls of their shell of a house like a naughty child or a caveman, in a cheap, coarsely creative attempt to bring art and colour to their lives.

The other place is a gay club, a little later on, as our protagonist is in the thralls of self-discovery. The club, through Caputo’s description, feels like being inside a drum as it is relentlessly beaten at from the outside. Both places in the book’s opening chapter have a dizzying quality to them, throwing us into the heart of a world we’ve had no chance to get accustomed to. But that is exactly how our protagonist himself has had to feel, both about his sexuality as he stumbles through the dark to figure it out, and about his lot in life – the destitute one he was born into.

The tone set by these two places is one that remains taut for the rest of the book. In fact, it only stretches itself thinner, beat by beat, without warning or apology. It’s difficult to endure, but we become all the wiser for it.

“When I think about who I am, I think about the night I dressed up as a butterfly … First, I discovered I was a poor man … Second, I discovered infinity, which is not the same as excess or repetition … Third, I became a father to my father.”

Six chapters and a little over 200 pages form the makeup of An Orphan World. Almost every one of these six chapters tosses us backwards into more than one place and time we are not familiar with. We do not know our nameless protagonist’s entire life; there is no exposition here, not really.

We are provided with fragments of his youth, and with these we must create an approximate mosaic of his life. That is, after all, how many of us see our own memories of childhood. We don’t remember them as they really were. And for our protagonist, his youth was simultaneously an attempt to stay afloat and a trial by fire. We are offered both, unrestrained, and almost in desperation.

And so, this is a story of a youth survived, far more than lived. In the place he lives, with the dark and deadly ocean on one side and the threatening, revealing lights on the other, our protagonist is not safe. Whether he leans towards the ocean or the lights, he risks danger.

It’s the unknown dark, where anything might happen and it will probably be bad; or the intense and familiar lights, where there is no hiding from your neighbours and your enemies, and while the light may be inviting, it is deadly. There’s such a crisp, clear metaphor at play here that seems shallow for how on-the-nose it is, but in fact it has exciting depths to it that play into both of our protagonist’s focal points: his relationship with his father and his own sexual discovery.

There is, for example, a moment early in the novel where a massacre has happened. A group of men have been slaughtered, their bodies littering the streets in grotesque and distressing poses. This was a homophobic attack, done with flippancy and gusto. When our protagonist walks past the scene as the bodies are being cleared away, he is stopped and threatened by the police.

One officer pinches at his face, stares him in the eye, and asks: “How come they didn’t kill this one?” That is the danger of the lights: they expose the truth at one’s heart and, as a result, puts them on display; threatening the privacy, the happiness, the safety, the life of anyone who walks through them. But what is the alternative? Unknown darkness, and just as much danger.

“All that exists is a policeman who’s just asked another policeman a question: how come whoever killed the others didn’t kill me? The only thing that exists is their laughter.”

This dark danger is exposed in An Orphan World’s other narrative track. Any time away from his father is time exploring his sexuality. At the beginning we are taken to a club. But later on, we go back in time to an online chat roulette of masturbating strangers reaching out to one another.

This chapter flits between the chat roulette and a place known as Steam, where our protagonist, a little older, is engaged in a series of intense, often frightening, disorientating, and painful sexual experiences. This loosely connected series of scenes feels like a surrealist play, a transition period of self-discovery as well as self-sacrifice for our protagonist.

It is difficult to confidently attach emotion to this scene. While it might be tempting to call it either cathartic or torturous, neither or both might be true because our protagonist behaves as a ragdoll, describing only the physical experiences and giving us little by way of his own reaction. He often calls himself a butterfly, and it is here we experience with him the struggle to become one.

In these raw and disorientating moments, An Orphan World succeeds at turning the turbulent life of a young gay man into both a requiem for innocence and an admittance that a life which is never safely lived must still, all the same, be lived.

The bumpy, endlessly tumultuous journey of Caputo’s protagonist, however, is very much felt in the novel’s execution as much as its themes and its story. There is a tonal dissonance that runs through the novel which is never reconciled. The perplexing dashes between moments in time offer us no catharsis and, while of course that is the author’s intention and I applaud it, this does make for reading that goes beyond being intentionally uncomfortable and into realms of emotional numbness.

So much endlessly raw affliction to the senses can make one feel overloaded and shaken with no relief in sight. The author here is well within his right to say that this is necessary to his point and I would not disagree, but the emotional impact provided is still worth pointing out.

What is also worth mentioning is that, while the translation by Adcock and Hughes is largely flawless in terms of its tone and impact, the choice of particularly British English phrases like ‘arse’ and ‘wanking off’ is consistently jarring, especially considering this is a Latin American novel that, while it could be set potentially anywhere – and that is part of the point – the translation then tempts us into picturing Blackpool rather than Cartagena.

Conclusion

There is an unquenchable fury burning at the heart of An Orphan World. Caputo writes with his pen on fire; furious at the threatening beast of a world that young gay men are thrust into, with the bright and overexposed lights of community on one side and the unknowable, quiet, lonely darkness of isolation on the other.

There is little friendship to be found here; little safety; little comfort. The world is deadly and aggressive, and it revels in that aggression. Even personal sexual exploration is painful and unfair.

This fear and anger is explored with dizzying allure in An Orphan World, as the story is melted down and then folded over itself again and again like the liquid steel of a blade – a blade that Caputo himself is forging to take on an unjust world, teeth bared and both hands on the blade as he goes.

Read our reviews of Charco Press’ other 2019 novels: The Wind That Lays Waste, Loop, and The Adventures of China Iron