Translated from the Czech by Paul Wilson

I had never read any of Hrabal’s poetry or prose before this book, which makes All My Cats an interesting place to start, being a non-fiction confession of sorts.

All My Cats is a sliver of a book that recounts, with great pain and suffocating guilt, an ageing life spent with cats. It is, as I have said, a confession of sorts, written with a prosaic narrative style and betraying a heavy philosophy that you’ll ponder on for days after setting it down.

All My Cats

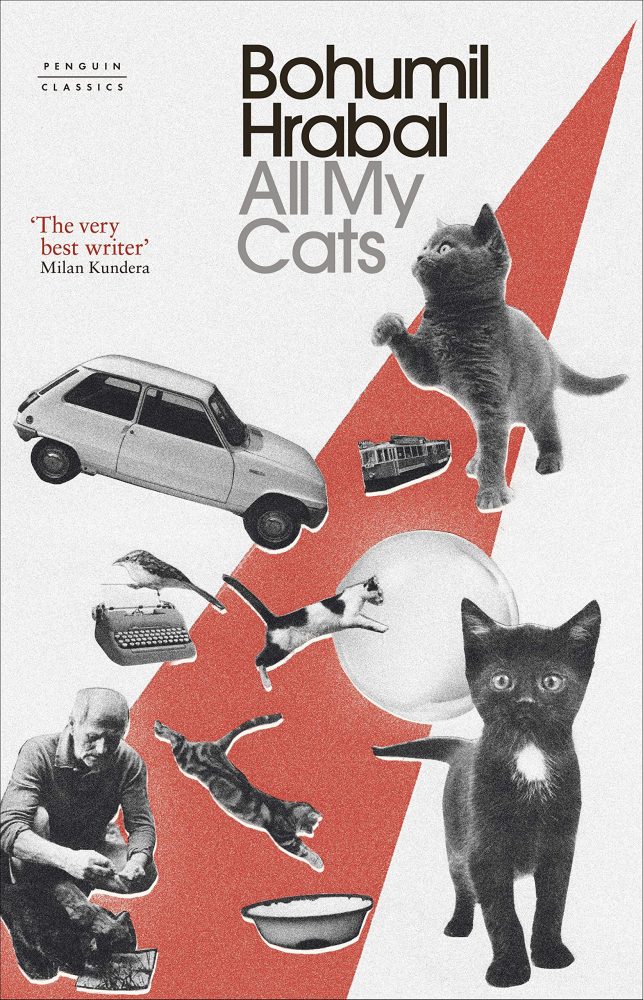

Hrabal died back in 1997, falling (at the age of 82) from a hospital window whilst apparently trying to feed the pigeons. This fact, along the Penguin Random House cover of All My Cats, paints an immediately vivid and colourful image of the man: a kind, soothing, and soft soul filled with great compassion for animals and a duty to securing their happiness.

And, while this is revealed to be true very immediately in the book, what the reader will find deeper in is something far darker and more heart-breaking. It certainly wouldn’t be going too far to say that the cover that has been designed for All My Cats is a misleading one.

Picking up this book with the assumption that you’ll enjoy the diary of a many falling in love with, and caring for, his cats is a real danger, and may quickly lead to the development of a few emotional scars. This is not to say, however, that All My Cats should not be read. In fact, it is one of the most affecting and thought-provoking reads of 2019.

Across 96 pages and a handful of chapters, readers are invited into the life of an anxiety-riddled man entering into his twilight years; a man who has worked a working man’s life until, at last, finding success as a poet and a writer. Now, Hrabal divides his time between a home in Prague and one in Kersko, a countryside area where he hopes to have the space to write and have his own peace.

That peace is shattered as his and his wife’s home in Kersko becomes overrun with five cats. Five cats who are quickly named and loved by Hrabal. His obsession with these cats, in fact, is all-consuming. For the first few chapters of the book, we are presented with the diary of a soft-souled writer with a sweet temperament and a kindness too much for this world, as he cares for these cats, admires them, respects them, observes, and lives happily alongside them.

All the while, his wife repeats the only line she ever speaks in the book – over and over like a mantra that forebodes, foreshadows, and haunts the narrative: “What are we going to do with all those cats?” It’s the book’s first line, and it repeats time and again. The answer comes like a cold slap: some of the cats have to die.

Hrabal takes it upon himself, more than once, to – as he puts it – murder his cats. Some are newborn kittens who will soon have kittens of their own; others become sick and turn feral. Reasons arise, and more often than not they are unclear and seem to be poor justifications for his actions.

Nonetheless, Hrabal proceeds to end the lives of his cats with increasing frequency and brutality as the book progresses. This is when All My Cats shifts from what it is assumed to be – the diary of a man caring for his cats – into what it is: a confession of guilt by a man who is always trying to do right by his own moral compass, and whose decisions rend his own heart to pieces and hollow him out almost entirely.

The emotional turmoil that Hrabal suffers through his own dark actions, which he believes are a greater kindness, a repeated euthanasia, is devastating. All the while his wife’s mantra is repeated again and again: “What are we going to do with all those cats?”

“I was guilty, not because I had beaten them to death but because I had murdered love. That was my sin. I was guilty in my own eyes, and toward morning, when they appeared to me, it was really me accusing myself, because I felt guilty and would go on feeling guilty as long as I remained in the world.”

While, initially, the disturbing graphical clarity with which we are presented the deaths of these kittens and cats is stomach-churning, the philosophical questions and musings at the heart of Hrabal’s narrative unveil themselves at just the right moment so as to stay our hand as we move to shut the book and leave it unfinished. All My Cats, as mentioned at the beginning, is a confession.

This Czech man who spent much of his life a poor, ordinary worker, is tormented and tortured by wave after wave of unbearable sorrow and guilt. He waxes poetic but with sharp honesty and clarity as he describes to us his torment. Here is when we see the layers of this narrative peel away. It is a book about responsibility. How much of it can we bear?

How do we know if we’re carrying it correctly? What is fair on us, and what is our duty? Where does it come from, and what does it offer us? There are questions asked in this book on the subject of duty and responsibility that I had never once before considered. And reading on as Hrabal interprets and attempts to handle his own responsibilities as best he can, and while his wife repeats her crushing mantra, is an exhausting exercise.

This book will leave you sweating, crying, and pounding at your skull as thoughts on personal responsibility spin and tumble in your mind like laundry.

The narrative, and these questions of responsibility with it, build to a sort of crescendo near the book’s conclusion as Hrabal comes face-to-face with a neighbour who desperately wishes to protect the birds in his garden. He accuses the cats of being a threat to their peace and their safety.

He is to the birds what Hrabal is to the cats. And so Hrabal now has a responsibility to keep the birds alive by keeping his cats under control. This compounds the sense of duty he is already putting upon himself, and the levy begins to break.

To say more would be to spoil the narrative conclusion. Speaking of which, it is worth remembering that this is a non-fiction biographical tale, which is a truly remarkable point when we consider the ethical and philosophical questions it poses. Hrabal’s life, as it happens to play out, exists as a perfect lesson in the topic of ethics and personal duty.

In that sense, it is reminiscent of Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor E Frankl – a piece of narrative non-fiction that is often heavily touted as a modern philosophical masterwork. And the same praise could, perhaps, be showered over All My Cats.

This is the story of a self-hating man burdened by the responsibilities he has chosen to take on, and infected by a writhing and spreading anxiety. He makes dreadful decisions that haunt him all the way to the grave. And the translation by Paul Wilson is so thoughtful and so thorough as to faithfully transfer the author’s palpable anxieties through its run-on sentences and painfully graphic details that read as obsessive words of self-flagellation.

It bears once more repeating that this is not a book for cat lovers, and it should not have been marketed as such. It is a warning against self-inflicted burdens being placed on those with fragile minds and soft hearts.

Conclusion

It is vital to approach this book with caution, especially if you find yourself simply drawn in by the cover and the blurb. Reading All My Cats is not a wholly pleasant experience. It is wrenching and turbulent; it may reduce you to tears. But it is an infinitely clever work that demands respect and admiration.

As a cat-lover, I wept, but as someone who opened his heart to the questions posed, I felt changed by the experience of reading this book; something that could perhaps be described as a parable that exists in service of finding the answers to questions of moral responsibility, personal duty, and the very philosophy of ethics.

If you are looking for some books more suitable for cat lovers, check out our list of books for people who love Japan and cats!