Where do you start reading an author like Kobo Abe? The post-war Japanese author and playwright has become known, most famously, as Japan’s answer to Franz Kafka. One difference between the two, however, is that Abe was able to finish his works. And of them, which ones are must-read novels?

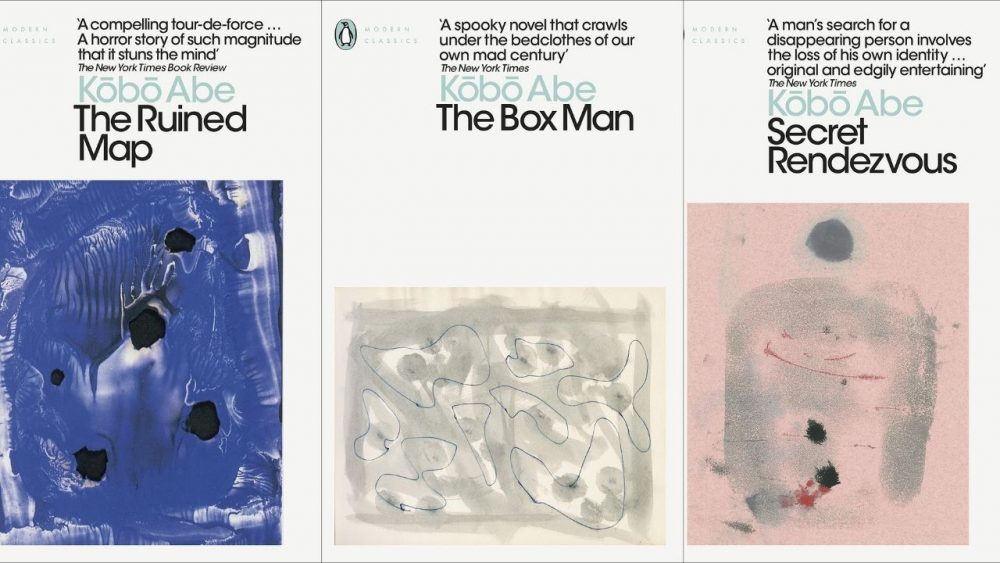

What we have here are three Kobo Abe novels, published in succession over ten years (from 1967 to 1977): The Ruined Map, The Box Man, and Secret Rendezvous.

All are relatively short novels and each one has elements of the Kafkaesque in its DNA. All are surrealist novels, though they differ wildly in the absurdism (with The Ruined Map being the most lucid and The Box Man the most abstract).

Fair warning: these three novels do not represent all of Abe’s works. His most famous novel – The Woman in the Dunes – is missing from this list, in part because it has a problematic and upsetting approach to writing women and sex. Though all of Abe’s novels take a raw approach to sex, that one is by far the most problematic.

However, despite this not being Abe’s complete body of work, they do beautifully represent a clear progression in style and theme for their author. Reading them in publication order is illuminating, and reading them out of order is chaotic in both a fun and a frustrating manner.

So, if you’re looking to explore the world and writings of the surrealist and Kafkaesque Kobo Abe, these three books offer the perfect place to start.

The Ruined Map

Translate by E. Dale Saunders

Of the three Kobo Abe novels discussed here, The Ruined Map is the longest, clearest, and most accessible.

Disguised as a straightforward piece of genre fiction — specifically, a pulp noir detective novel — it steadily allows Kobo Abe’s signature surrealism to seep in through the cracks bit by bit, but never truly overwhelm the reader in the way that The Box Man does.

At a little over 200 pages long, The Ruined Map is only slightly longer than The Secret Rendezvous, but it probably takes less time to read due to its clearer, more traditional, less absurdist approach to writing. It’s a testament to E. Dale Saunders’ translation prowess that they were able to translate both The Box Man and The Ruined Map (two novels so distinct from one another in terms of narrative and structure) so wonderfully.

The Ruined Map begins in a straightforward manner, with a detective – our protagonist – arriving at the home of a woman who has hired him to help her find her missing husband.

Though, if this isn’t your first Kobo Abe book, you’ll already be aware of some of his trappings here. Namely, the fact that he spends an ungodly amount of time on minor, insignificant descriptions, while character interactions come off as circular and like they are treading water. It’s surrealism but in a subtle, almost invisible kind of way.

This reserved approach to surrealism perhaps demonstrates how Abe’s writing evolved over time. Of these three novels, The Ruined Map was the first to be published, followed by The Box Man, which is surrealism unfettered and gloves off.

Secret Rendezvous is arguably the smartest and strongest of the three, balancing absurdism with genuinely smart Kafkaesque themes; it only makes sense that this was the result of Kobo Abe honing his skills as a writer and literary philosopher.

As for the story, we follow our detective protagonist as he attempts to find this missing husband. The man was in his thirties and working a desperately dull job (very similar to the protagonist of Secret Rendezvous). One day, he up and vanished, with his wife waiting six months to hire a PI to track him down. When asked why, she blames her brother who urged her to be patient. The brother is called upon next.

The wife, by our detectives own deductions, is a borderline alcoholic who comes across jumpy, unsure of herself, and pathetically meek. She is unhelpful, offering the detective clues which don’t seem like clues at all.

Her brother is more clear-cut as a character but also more manipulative and playful with the truth. Neither are particularly helpful, and it’s from here that our protagonist must descend into more dangerous territory in his search for the missing man.

While The Ruined Map does come across as a pulp detective story, this is all just window dressing. Though that window dressing does make for a far more accessible novel for first-time readers of Kobo Abe’s works. The real meat of the story comes from its execution and how Abe, still in his early writing years, is beginning to play with surrealism as a narrative and world-building mechanic.

As mentioned before, the surrealism is drip-fed through the writing style of the novel. The story and mystery remain ever intact but the riddle-talking characters, the feeling of running on the spot. The obsessive and overly detailed descriptions of ordinary, unrelated things is loudly reminiscent of Twin Peaks. So much of what makes this novel surreal applies to David Lynch’s masterpiece.

And so, I’ll say this right now: any fan of Twin Peaks would likely adore this novel. Its missing person setup, detective protagonist, obsession with mundane detail, and off-kilter world populated by unsettling and sometimes dangerous characters has an intense Lynchian feel to it. I can’t help but wonder if Lynch was inspired by Kobo Abe’s writing. It seems impossible that he wasn’t.

Kafka’s influence can still be felt in this novel’s themes and execution as well. The titular ruined map can be applied to the Tokyo our detective explores, as well as the mental map he is forming from the clues that he follows. Perhaps most importantly, the fact that the map is ruined feels emblematic of the book’s strongest theme: that we can never truly know one another.

The circular behaviour of the conversations in this book, the concept of a ruined map, and the endless searching that our detective engages in – it is all emblematic of an issue with personal relationships. Secret Rendezvous and The Box Man both dwell on this concept as well.

It seems that Abe had an issue with knowing, understanding, and even trusting our fellow man, and he chose to express this paranoia and frustration through Kafkaesque surrealism. It is a question many of us have considered: how can we ever actually know one another? We only know what our senses tell us. We rely on observing habits and trends to form predictions.

When we say “I know you” to someone, we only mean that we know their habits and their typical behavioural loop. We know them by sight, sound, maybe smell. But what does it mean to know someone? And if we can’t, how do we trust them?

This question is everywhere in Abe’s writing, and seen just as strongly here, though it is far less forceful, abstract, and aggressive. That’s what makes this loose piece of genre fiction much more accessible. Ultimately, it’s a superb place to start reading Kobo Abe as you become accustomed to his themes, ideas, philosophy, behaviour, and style.

Buy a copy of The Ruined Map here!

The Box Man

Translated by E. Dale Saunders

At 155 pages, The Box Man is a short yet incredibly dense novel – the kind which takes as long to read as a more straightforward 400-page book might. Its density is due to the intense and dizzying surrealism which frames its narrative.

The Box Man is intentionally hard to follow, feeling at times like a labyrinth. It can make the reader feel physically exhausted as they attempt to keep track of its events and characters, but the reward for persevering is considerable and satisfying.

The Box Man is set in a Japan where it seems not uncommon for men to abandon their ordinary lives, swapping their homes for cardboard boxes. They occupy these boxes like hermit crabs, writing notes and scrawling on the insides of their boxes.

Our protagonist is a box man who writes in shifting perspectives. It quickly becomes hard to tell when he is describing himself or someone else, or even when he is being described by a secondary narrator.

Our nameless box man has been living outside of the bounds of society for a hazy amount of time, and he begins his narrative by describing the ideal box for a box man, recounting dreams, and giving an example of how one might become a box man.

When he is offered an impressive sum of money to discard his box in the ocean, he decides to follow the woman who made the offer – a nurse – back to the hospital. It’s at this point that the novel’s narrative becomes almost impossibly tangled.

While The Box Man quickly enough drags its reader down into a frightening mire of twisted narratives, distorted places, fractured sequences of time, and multiple narrators, it never loses its keen eye for exploring big themes and ideas. It’s these themes which save The Box Man from being a jumbled, incomprehensible mess.

Like many of Kobo Abe’s works, The Box Man is a Kafkaesque work (in fact, the writer is often considered Japan’s answer to Franz Kafka), but this novel is only loosely Kafkaesque. It is also a novel inspired by socialist ideals, anarchistic dreams, and surrealism.

Our protagonist wishes to live outside of society, mesmerised by the allure of being a human hermit crab. He wishes to free himself of the very concept of identity, offering the reader the perspective that identity is a social construct that can be removed and discarded like an old jacket.

At the novel’s outset, the metaphor of the box man is clear enough, and we get to see the pros and cons of discarding one’s identity.

Abe explores whether or not this is even possible, and asks us to ponder what it might even look like to live outside of society, especially when his protagonist remains living in a city, using money, scavenging human artefacts, and bartering with other people.

It’s clear that Kobo Abe is intrigued by what his box man represents, but that he also sees the hypocrisy in it. And that hypocrisy is perhaps the novel’s greatest strength.

Hypocrisies, arguments, parallels, and paradoxes abound in The Box Man as Abe seems to spend the novel fighting against his own ideas and ideals. His protagonist is neither good nor bad but acts as a vessel for his own musings and frustrations.

Our titular box man is a fairly reprehensible person, especially when it comes to women. Before abandoning his ordinary life, he was a photographer — by his own definition, a ‘voyeur’.

In one chapter, after becoming sexually obsessed with the nurse he pursues, the box man even lucidly ponders whether or not he became a box man only to continue his perverted hobby of voyeurism, now from a vantage point of increased anonymity and, thus, power.

The elephant in the room here is that Abe has a track record of writing women badly. While I haven’t read his most famous work, The Woman in the Dunes, it has been criticised for its rape scene and its tool-like use of a woman as a plot device.

This kind of writing, whether it serves a purpose or not, is inexcusable. It’s tiresome, frustrating, and aggravating, and I won’t make any apologies for Kobo Abe writing women as tools rather than characters. This problematic approach to women rears its ugly head in The Box Man as well, though it is arguably far less clear-cut.

While his main woman character (the nurse) is nothing more than an object of sexual desire for the box man and his counterpart (the doctor-cum-imitation box man), she does seem to represent a bigger thematic point. With the box man being a perverted voyeur, it could be argued that Kobo Abe is using him and the nurse to attack the toxicity of masculinity.

This could easily be me giving a writer the benefit of the doubt, as well as me projecting more modern considerations on a long-dead writer, but the depiction of the titular box man as a repulsive, dangerous, pathetic character is hard to ignore. Entitlement, fetishism, immaturity — it’s all here in full view.

Looking at the box man’s obsession with the nurse – the ways in which he fetishises, watches, fantasises over her – combined with the fact that he is a delusional, broken man living in a cardboard box, it all stinks of what we today refer to as incel behaviour.

The box man is a lonely, delusional loser, living in denial, behaving like a man-child, acting dangerously, lying to both himself and the reader. It doesn’t seem to be much of a stretch to view Abe’s box man as a sad, pathetic representation of the modern toxic man.

This is backed up by his own unreliable narration, his clinically dry, overly scientific way of seeing and writing about the world, and his twisted, hypocritical, paradoxical way of describing the world and the people around him. The box man seems to think that he is free, that he is smarter than everyone else, and yet he is ultimately a lonely, confused pervert in a cardboard box.

None of this excuses Abe’s poor characterisation of his woman character, but it is aided by the only other depiction of a woman in the novel. In one of the final chapters of The Box Man, a young boy watches a piano teacher in the bathroom. He is another voyeuristic pervert.

This time, however, he is shamed by the woman and punished by being forced to experience that same vulnerability. This adds credence to the idea that Kobo Abe is shaming men for their sense of entitlement; their false, unearned superiority; their perverted, shameless behaviour.

Given just how surreal The Box Man is, it is easy enough for every reader to find an entirely unique interpretation of its story, characters, and themes. This is just my interpretation. But, from where I’m standing, The Box Man seems to be a clear enough condemnation of toxic male behaviour.

After all, his perverted, unreliable, hypocritical narrator spends his days writing notes while living inside a cardboard box, naively believing himself free of the shackles of society.

Buy a copy of The Box Man here!

Secret Rendezvous

Translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter

Of all of Kobo Abe’s novels, Secret Rendezvous is the one which so many inspired works can be traced back to. Similarly, it is the one most obviously inspired by the man Abe is so often compared to: Franz Kafka.

Reading Secret Rendezvous, it is immediately apparent how much of Abe’s stylistic and thematic DNA is shared with Haruki Murakami, with Murakami so often writing about lost women and the frightened, overwhelmed men who search for them.

Secret Rendezvous also revels in that quaint Murakami absurdism: a narrator from a bland, ordinary life is thrust into an impossible, absurd world and yet so admirably adapts and takes it all on the chin. The novel’s narration is split in two, with our protagonist in the present recounting his recent past experiences.

The past, written in the third person, takes up the bulk of the story, but the present framing device also moves forward gently, with the two edging closer as the gap between them shrinks.

Our nameless protagonist is a man searching for his wife. At the outset of the novel, an ambulance arrives at their house in the middle of the night to take her away, despite her being perfectly healthy and nobody having called for an ambulance.

She is immediately stolen away and our man gives chase, arriving at an endless, labyrinthine hospital. It’s the stuff of nightmares, with the hospital setting constantly growing and shifting. As Secret Rendezvous progresses, the hospital bloats so much as to be described (rather nonchalantly) by the narrator as having valleys.

As our protagonist searches for his wife, he meets a cast of anonymous characters, many of whom talk in riddles, take on multiple roles, behave as both doctors and patients. They give him tasks, offer him a job and a room, and our man’s main point of contact believes (or hopes) himself to be a horse.

However long our protagonist spends searching for his wife, he makes no progress. Soon after arriving, he discovers that she was being held in a small room with no exit, and yet somehow she has vanished. Scenarios like this increase in frequency and absurdity as time goes by. How much time is unclear, with the hours and minutes following as few rules as the space and architecture of the hospital itself.

It’s evident just how inspired Murakami must have been by the works of Kobo Abe, and Secret Rendezvous in particular. So much of the tone, characters, and events of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle can be found in the architecture of Secret Rendezvous.

Beyond Murakami, there are clear links between the genetics of this novel and The Factory by Hiroko Oyamada.

While her novel is intensely Kafkaesque with its aggressive and exhausted take on bureaucracy and work culture, its depiction of the endless, all-consuming physical world of the factory is so tangibly reminiscent of the hospital Abe describes in this novel.

Speaking of Franz Kafka, it’s no secret that Kobo Abe was heavily inspired by the Bohemian writer.

He even once visited Kafka’s home in Prague. But more than any other Abe novel, it’s Secret Rendezvous which feels like a direct homage to Kafka, not just a novel inspired by him.

The setting, characters, and themes of Secret Rendezvous read like a perfect blend of Kafka’s two novels: The Trial and The Castle. In The Trial, Josef K. is arrested for a crime he didn’t commit and doesn’t understand. He desperately seeks answers and finds nothing, only growing in desperation and confusion. In The Castle, K arrives at a village and attempts to gain access to the castle, only to be denied entry.

Elements of both novels can be found in Secret Rendezvous, with our protagonist clueless as to why his wife was taken (similar to The Trial) and unable to gain access to her (like in The Castle). Beyond its inspirations and the mark it left on Japan’s literary world, Secret Rendezvous is a masterpiece in its own right.

It isn’t only the gross, monstrous hospital setting — ever growing, changing, remaining unknowable and all-consuming — which exists to terrify and alienate both the reader and the protagonist, but also the people who populate it.

Like the characters in a Silent Hill game or a Sarah Kane play, the people our protagonists meets, seeks help from, and must come to rely on (despite their riddle talk and impossible behaviour) are distracting, untrustworthy, and demanding.

Some of them have two or more jobs within the hospital and some seem to be both doctors and patients. One is a horse.

There is genuine horror in this novel’s absurdism, and what makes it all the more unnerving is how our protagonist seems to be keeping his head above water the entire time, almost as though he is becoming accustomed to the world of the hospital and those who populate it, especially once he is given a role of his own to play.

It’s here that Abe’s love for the theatre becomes most evident (it’s not hard to imagine an Artaud stage adaptation of this novel). Beyond the roles these characters play, there’s also Abe’s patented use of raw sexualisation.

Though, while The Box Man and Woman in the Dunes explicitly sexualised the female form, Secret Rendezvous has fun with exploring male genitals and masturbation. This time around the purpose seems to be blurring the lines between sexual pleasure, clinical examination, and physical pain.

That clinical behaviour extends to Abe’s tone and writing style as well. It has been remarked upon by other writers how Abe has a scientific approach to writing, with his characters maintaining a clear-headed, logical approach to the events of their own stories, however surreal and absurd they may be.

This helps add to the unsettling nature of Secret Rendezvous as our protagonist keeps an impossibly level head no matter what new wall is raised in front of him. While Secret Rendezvous is so explicitly inspired by – and even reads like an homage to – the works of Franz Kafka, it also takes on a life of its own and has its own unique themes to explore.

Kafka was intensely obsessed with the paralysing, confusing, alienating, inhuman bureaucracy of post-industrial Western life. Secret Rendezvous, on the other hand, is more concerned with how our jobs, our roles, our relationships, and even our places of working and living seem to mould and shape us into ugly, unknowable, unhelpful things.

Alienation is still a key Kafkaesque theme here, but it’s what causes that alienation and what it leads to that makes Abe’s novel uniquely its own piece of art.