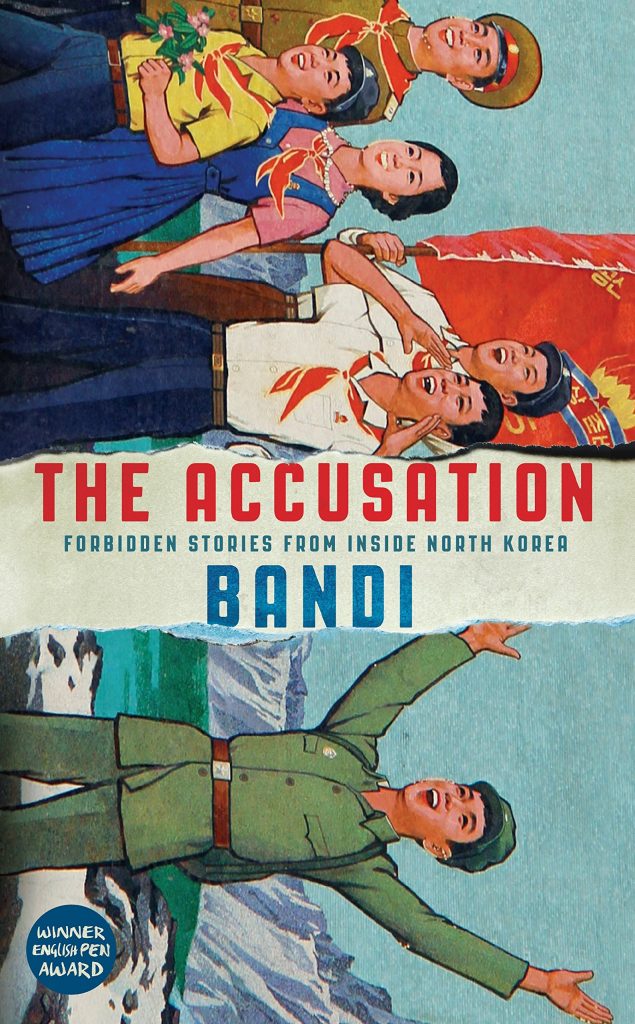

It is difficult to know where to start when discussing a book like The Accusation. Smuggled one by one out of North Korea and into China as scribbled manuscripts, and here collected at last as a gorgeous hardcopy.

Bandi’s collection of short stories, The Accusation, is not just a valuable insight into ordinary (read: terrifying) daily life in North Korea but also a truly fantastic collection of beautifully written, lovingly translated, deeply metaphorical and exploratory fiction.

Bandi (반딧 – Korean for ‘Firefly’) is a pseudonym out of necessity. Knowledge of the existence of these stories by the North Korean government would mean death not only for the author, but for his family, and a black mark for any surviving generations.

Where Did it Come From?

The stories in this collection were written in the early nineties, after Bandi became disillusioned with the regime and lost family and friends to both famine and defection. Within these pages we have a small supply of fictional tales which each perfectly reflect a unique aspect of the torturous existence of the average North Korean citizen.

These stories paint a vivid image of both Pyongyang and the smaller outlying towns. They give us insight into the jobs, communities, and homes of ordinary people, whose meaning of ‘ordinary’ is chillingly different from our own.

Political Ideals

At least once during my reading of each tale did I think to myself that this reminds me of something from Animal Farm or 1984, something deeply Orwellian, only then to remind myself that this is all real.

The tales may be fiction, but they are perfect reflections of the everyday. That thought left me cold again and again. The book opens with a poem denouncing Marx and his communist ideals. It is a short poem of two stanzas, and it is the quickest thing to bring me to tears that I’ve ever experienced.

If I may be personal for a moment, this poem knocked me back for two reasons:

The first is that it is a perfect framing device for the rest of the book. It allows the reader to understand the world they are about to walk into, a world that is as

‘black as a moonless night at the year’s end’.

The second reason is that, as a young liberal who ideologically places himself on the side of socialism, it was truly heart-breaking to have something as simple as a short poem bring one’s principles into question. Bandi points out to me that, while socialism may be something to put our faith in, people are not. It is people who ruin ideas.

I have so much respect for Deborah Smith, for putting so much heart into her translation, for allowing Bandi’s beliefs and his anger to be translated so seamlessly.

The Accusation

The book contains eight stories. Each of which provides us with a different perspective. For example:

- a retired and travelling grandmother

- a desperate miner seeking reunion with his mother

- an old and disillusioned war veteran

Every story also shines a light on a different issue within the closed borders of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

In recent years, our newspapers and documentary crews have shown to the world the DPRK’s laws and class system, its televised shows of military power, and its focus on policing and surveillance. Each of these familiar issues is presented and examined as a central theme in Bandi’s Forbidden Stories.

Life of a Swift Steed

As an example, let’s explore the story from The Accusation which impressed me most, with its heavy metaphors and probing of inner demons: Life of a Swift Steed.

The third tale in the book is told from the perspective of an office worker, Jeon Yeong-il. He receives a phone call from the police concerning the behaviour of a fellow worker, Seol Yong-su, whom Jeon knew intimately growing up due to his own late father’s friendship with Seol.

Seol is elderly, but still works as a cart driver for a factory; living out his childhood under the Japanese occupation of Korea and then performing as a wrestler in his army days, going by the nickname ‘Irya Madya’. Seol finds himself in trouble with the police after brandishing an axe and threatening police workers who had attempted to remove a branch of the elm in his yard as it had become tangled in some power lines.

As the story unfolds, we learn the importance of this elm, planted by Seol during the early days of the DPRK; and a twin tree had also been planted by Jeon’s father for the same reason:

“For Seol Yong-su, the elm was a banner bearing the slogans of struggle, a placard encouraging him to keep up hope, reminding him of the blissful future which lay in wait […] This is the song that sums up his life, painting the picture of communism’s shining future, where everyone will eat meat and white rice every day, wear silk clothes, and live in a tile-roofed house.”

Later in the story, we see how the man has grown old and tired, and despite the struggles and toils of his unending labour and his unwavering belief, the tree too has grown old and has not borne fruit. And so the foundation of Marxism – workers controlling the means of production – has come crashing down, and we learn that the axe which Seol brandished against the police was, only moments before they arrived, about to be used on the elm itself.

He wished to cut down the dream which had failed him, but even that right was almost taken from him by the state police.

Parallels with Orwell

Whilst reading The Accusation I saw time and again parallels between the man Seol and Orwell’s Boxer from Animal Farm, a strong carthorse who represents the Russian proletariat and who works tirelessly to build a brighter future for the people. And as Boxer’s labours prove fruitless, as do the man Seol’s.

But more than this comparison is the realisation that Bandi very likely has never been given the chance to read Orwell, and all the same has the objective ability to see the same injustices that Orwell had seen. Often we cannot see the wood for the trees, and that can often be assumed doubly true of a country where people are indoctrinated so thoroughly from birth. So we must show the utmost respect for Bandi.

Eyes Wide Open

Bandi, a member of the DPRK whose eyes are wide open and allows us to see the truth of life within those sealed borders. Every tale in The Accusation has a lesson to teach us. From warning signs about the lies people believe with all their hearts:

“If capital is the weapon of capitalism, the weapon on socialism, which governs all of our lives here, is the proletarian dictatorship. A dictatorship of the people! Yes, the people of this city understand all too well the reality of that idea.”

To the resolutions they must build for themselves if they are going to reject those same lies:

“In this country, a mother has only one wish when she brings children into the world: that their passage through life will be blessed. But if she knew for a fact that what lay in wait was an endless path of thorns? She’d need the cruelty of a hardened criminal to condemn a child to that.”

Yu Hua once wrote that growing up during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution moulded in him the belief that:

“The people are Chairman Mao, and Chairman Mao is the people.”

This concept has more truth, and equally as much deceit, to it in modern day North Korea as it had in Mao’s China. Bandi knows this, and I wish in my heart of hearts that I could meet him, shake his hand, and thank him for providing the world with the rare and marvellous treasure that is The Accusation. Sadly, I know that this may never be allowed to happen.

If you like this article, you may like How China Got Me Interested in North Korea or other fiction translated by Deborah Smith, such as The White Book.