Translated from the French by Euan Cameron

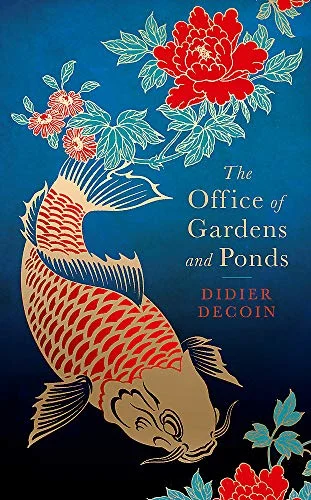

‘Don’t judge a book by its cover’ is a metaphor. It’s about humanity; it’s not really about books. This is important because we do judge books by their cover art, and their titles, and their fonts. The Office of Gardens and Ponds has the most beautiful cover I’ve ever seen.

It speaks to my adoration for Japanese aesthetics, and the long, clunky, strange title reeled me in enough to get my excitement high. This gentle hype was well-placed: The Office of Gardens and Ponds is, easily, one of the best novels I’ve read in my almost three decades on this planet.

It purportedly took legendary French author Didier Decoin fourteen years to complete this novel. That info paints an image in my mind of a man locked away in a lakeside cabin in Switzerland, stacks of books on Japanese history and culture surrounding him. He pores over them for years.

He takes the odd trip to Kyoto and Niigata for his research before returning to the cabin. He does this for more than a decade before emerging with a 300-page book that gently glows golden, and he smiles, his eyes glistening.

I doubt that much of what I’ve guessed at here is true, but the way this story reads – the delicacy of its language, the focus of its plot and its characterisation – it could all very well be true. This is the kind of book which words like ‘masterwork’ were made for.

“I’ve seen Katsuro come back from the river exhausted, muddy, soaking, and sometimes bleeding, but never disappointed with his fishing. Oh no, never ever! These carp that are travelling with me are the last ones he caught. Afterwards, he departed from this world.”

A Great Journey

Set during the Heian Period of 12th Century Japan, at a time when Kyoto – the former capital – was known as Heian Kyo, Miyuki is a fisherman’s wife. Her husband, Katsuro, is twice her age and the greatest carp-catcher in their hometown of Shimae.

After catching a batch of fine koi, he drowns. Beyond being their town’s fisherman, Katsuro was also given the job of carrying twenty koi to the capital, where they would be used by the emperor as sacred decoration in the Imperial Palace’s ponds. Now that Katsuro is dead, his grief-stricken widow, Miyuki, must take up the task and make the month-long journey to the capital.

The magic of The Office of Gardens and Ponds comes first from its structure and its narrative: it is modelled after a folk tale. Here we have a female protagonist, naïve about the world around her. A task is thrust upon her and she must journey out on foot, carrying a great physical and emotional burden.

She does not know the way and must use stories told by her husband to piece together the route ahead of her – inns he stayed at, landmarks he’d described. On her way she will meet dangerous people and pass through difficult trials, all to arrive at her seemingly mystical destination.

“Miyuki … had only lived two years: a first period, very long, very pointless, up until her marriage, and a second one, dazzling but too short, that had come to an end when the villagers of Shimae had brought back the frozen, muddy body of her husband.”

So much of what makes up this journey is reminiscent of folk tales both European and Japanese. Ancient Japanese tales like A Woman and the Bell of Miidera and The Adventures of Little Peachling marry with the stories of Andersen – stories like Thumbelina and The Little Mermaid – to create a novel that is soaked in the charisma, the darkness, and the eroticism of old fairy tales.

Much More than a Fairy Tale

The twist here, which is what elevates it far above its influences, is Miyuki herself and what she encounters upon arriving at the capital. For the first half of The Office of Gardens and Ponds, Miyuki makes her journey alone while reminiscing to herself over memories both happy and sad.

These musings are often erotic; they release sparks that let us know of the romantic fires within her. Miyuki is a woman of life and love. She is a person of burning flame, and she draws the reader in as white light does a helpless moth.

The second half of the story concerns the state of the capital, Heian Kyo, and it is certainly not worth spoiling here. But it is in this shift that we see the true scope of this story – the intentions of the author. While at first, we see a modern take on traditional folk tales, suddenly now we can see that this book is, in fact, topical. It is political. It is bold and assertive in its message.

A recurring motif which builds heavily after the novel’s midpoint is that of scent. Watanabe, Director of The Office of Gardens and Ponds remarks on Miyuki’s smell: at first claiming that she stinks, as though she is spoiled, impure, rotten. Then this smell begins to change something in him, and his approach towards her shifts.

Watanabe is also the source of much of the book’s wit and comedy. He’s an officer in the emperor’s court, but he is also a boorish and frightfully silly man – his underling, Kusakabe, even more so. The two play off one another, at times, like Sirs Toby Belch and Andrew Aguecheek from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

“This smell reminds me of overwashed, overheated, overcooked rice, and of a silk dress that a careless maidservant has left out in the rain … it reminds me of sickness, of tainted beauty, and also of dying birds – but all of these are rather similar, are they not?”

The attitude of Watanabe – and indeed of the court at large – towards Miyuki is that of modernity, sophistication, pomposity towards the more simple, dirty, unpolished, uneducated rural world which Miyuki hails from. It’s the Savages song from Disney’s Pocahontas.

It’s city vs country. It’s the ironically naïve, brutish, alpha male attitudes of the capital claiming that it is the farm girl who is dreadfully unclean. The dialogue at the points where this message is at its most heavy-handed is full of delightfully clumsy rhythm, weighted with dank metaphors and witless venom. It’s a dark riot of awkward comedy that’s a joy to read.

The lazy, ill-gotten wealth and power of those at the capital, pitted against the honest, good, clean life of a fisherman’s wife who arrives at their door at the end of a great pilgrimage – it’s enough to churn your stomach. But you’ll have fun with every moment of it.

Conclusion

There is so much to cherish about The Office of Gardens and Ponds. The way things stand right now, this may very well be my favourite novel of 2019. For a French novelist to capture so much of the bureaucracy that is rife in Japanese society is fantastic. To take that bureaucracy and inject it into a setting that is a thousand years old, overgrown with lush vegetation and towered over by godly mountains, was a bold and powerful move.

If you adore Japanese mythology, history, tradition, and aesthetics as I do, this book will have you weeping tears of joy. If you loathe class divides, pomposity, and the unnatural imbalance of human society as I do, this book prod at your deepest frustrations.

And if you want to know what a modern take on a Japanese folk tale, mixed with European fairy tales and a dash of Shakespeare could possibly look like, this book is, indeed, that. In short, there is nothing this perfect book cannot do or be. I will hold it close to my heart for years to come. I will re-read it once a year.

I will thank Didier Decoin forever for sacrificing fourteen years of his life to bring us this book. It might not be my place to say but, from where I’m standing, his sacrifice was worth it.

If you’re interested in learning more about Japanese modern and historical culture then you might enjoy: books to Read Before Visiting Japan or our review of Japan Story.