In 2017 the Nobel Prize for Literature was won by the illustrious Kazuo Ishiguro, and though he is a British citizen and writes exclusively in English, he is of Japanese birth and his first two books were set in the land he first called home.

Ishiguro is my favourite author, and his win had me soaring (though I am hoping for a female Japanese writer to gain wider recognition in the western world soon – a prize for Banana Yoshimoto wouldn’t go amiss). With Ishiguro’s win, I decided to travel back and read Japan’s other two Nobel Prize winners: Kanzaburo Oe and Yasunari Kawabata.

Here, in a nutshell, are the gifts each man has given to the world of literature.

Kazuo Ishiguro (Nobel Laureate 2017)

As he delivers his Nobel acceptance speech, Ishiguro muses on the Japan of his memories, a place he left at the age of five. He recalls specific details of his early life in Nagasaki, and as he does so he remarks:

‘As I was growing up, long before I’d ever thought to create fictional worlds in prose, I was busily constructing in my mind a richly detailed place called Japan. A place to which I in some way belonged.’

As a young man Ishiguro was forced to come to terms with the fact that his own personal Japan was nothing that he could visit in the real world.

‘The Japan that existed in my head might always have been an emotional construct put together by a child out of memory, imagination, and speculation.’

This realisation brought him and his stories together.

‘What I was doing was getting down on paper that world’s special colours […] its dignity, its shortcomings; everything I’d ever thought about the place before they faded forever from my mind.’

And so from this need to write about his fantastical alternative Japan, the one that had been left to flourish in his imagination, the young Ishiguro wrote two novels: one set in Ishiguro’s hometown of Nagasaki (A Pale View of Hills, 1982) and the other in the capital, Tokyo (An Artist of the Floating World, 1986).

The theme that runs through both of these novels, as well as Ishiguro’s third (The Remains of the Day) is that of memory, specifically its ability to betray us and our willingness to ignore or distort it. Memory is not reliable, and it can be used as a tool for lying to others or to ourselves.

Looking back to Ishiguro’s fantastical memories of Japan versus the real Japan that continued to exist without his existence in it, it’s easy to see why he puts so much attention on the power of memory He has managed to build his career as a genius wordsmith and story craftsman around this idea of the daunting power of personal memory versus history.

In A Pale View of Hills we have our protagonist, Etsuko, now an aged woman living alone in rural England. Her youngest daughter, Niki, comes to visit her after the suicide of Niki’s older sister, Keiko. This sets in motion a painful journey of recollection as Etsuko wanders through memories of her past life in Nagasaki and her friendship with the elusive, naïve, and irresponsible Sachiko.

Parallels are soon drawn between these two mothers, and Etsuko’s relationship to her daughter and her own memories continue to grow brittle and strained.

Ishiguro’s second novel, and my own personal favourite (as well as that of several fans and critics), is An Artist of the Floating World. Set in Tokyo during the fallout of World War II, the story follows our narrator, the once famous ukiyo-e painter Masuji Ono, as Masuji deals with the preparations for his youngest daughter’s upcoming marriage.

As the arrangements progress, Ono is forced to face his past and the relationship between his art, his politics, and Japan’s role in the second Great War. The character of Ono is absolutely one of the most subtly complex to be found in modern literature.

A father who begins his tale stoic and self-assured, his visage begins to crumble over time and his way of seeing the world and his place in it is called into question time and again. Repeat reads of this beautiful masterpiece uncover deeper and deeper layers to Ono’s character. An Artist of the Floating World is an undisputed masterwork of literary fiction, and reason enough to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

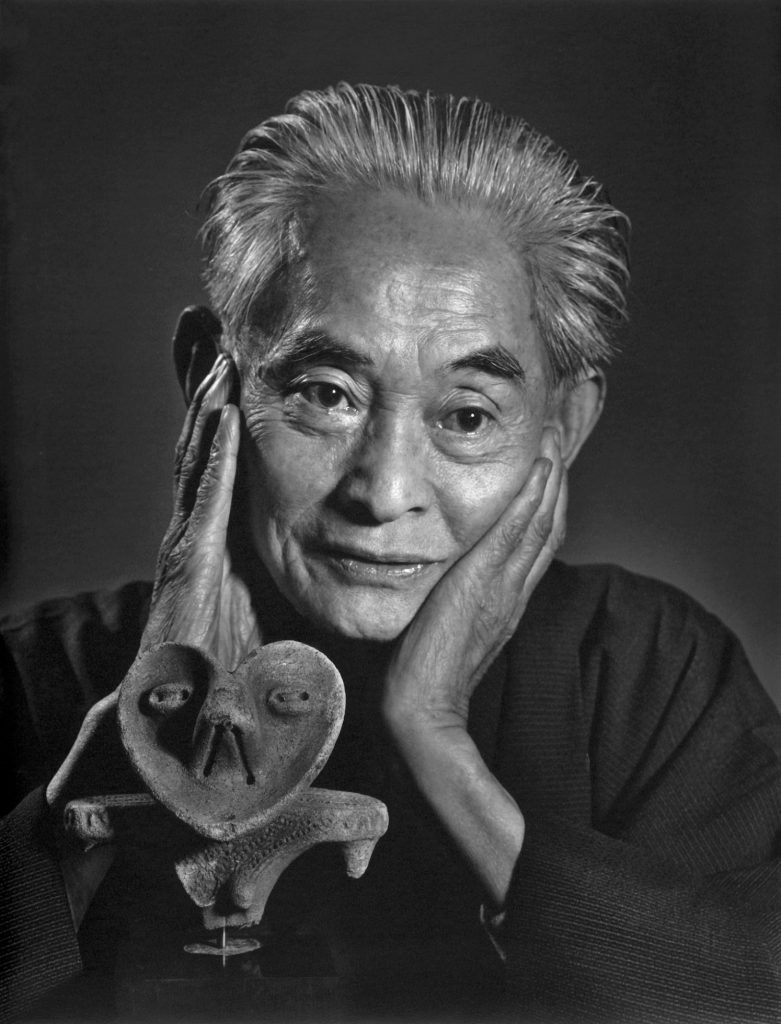

Kenzaburo Oe (Nobel Laureate 1994)

Of the three winners, I have chosen to give Oe the title of ‘The Rebel’ because, as The Paris Review put it:

‘In 1994 Oe accepted the Nobel Prize in Literature but then declined Japan’s highest artistic honour, the Order of Culture, because of its ties to his country’s emperor-worshipping past. The decision made him a figure of great national controversy, a position he has frequently occupied in the course of his writing life […] He has remained in the political spotlight ever since and considers his activism to be as much his life’s work as literature.’

In the same Paris Review interview, Oe summed up his own political beliefs in a simple, beautiful sentence:

‘In principle, I am an anarchist. Kurt Vonnegut once said he was an agnostic who respects Jesus Christ. I am an anarchist who loves democracy.’

Much like Ishiguro, Oe’s writing stems from his interactions with his own Japan, but while Ishiguro’s Japan is one somewhat fantastical, Oe’s is one of political turmoil, social struggle, and the fight for change.

Born in 1935, Oe lived through the Second World War and saw the devastation and the aftermath of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

This, of course, had a profound and lasting impact on his writing. Most notably, his long essay Hiroshima Notes (1965), which describes the thoughts and lives of the victims of these tragedies.

Arguable Oe’s most famous work to date, The Silent Cry (known in Japanese as 万延元年のフットボール; Man’en Gannen no Futtoboru, literally ‘Football in the First Year of Man’en‘) tells the story of two brothers, the narrator and introverted academic Mitsusaburo, and his borderline-eccentric younger brother Takashi, who has just returned to Tokyo from New York.

After Mitsu and his wife make the choice to leave their handicapped infant child in an asylum, and Mitsu struggles with learning about the suicide of a friend (in a particularly and oddly erotic manner), he and his brother Takashi return to the village of their youth, to do business and battle with a Korean slave-turned-CEO known as ‘the Emperor of Supermarkets’ who wishes to expand his empire.

At its most philosophical, The Silent Cry is an examination of the ruination both modern/urban and ancient/rural Japan has seen, at both its own hand and that of Western influence. As the Japan Times noted about the novel:

‘Metropolitan Japan is selfish and violent, riven with riots, while rural Japan is disintegrating, populated by freaks such as Jin, “the fattest woman in Japan” and Gii, a draft-dodging hermit.’

The Silent Cry is a rare novel, the kind that may rightly win its author a Nobel Prize all on its own, and a perfect place to start your journey into Kenzaburo Oe’s works and philosophies.

Yasunari Kawabata (Nobel Laureate 1968)

What arguably defines the writing of Japan’s first Nobel Prize winner is his ability to capture a scene or a moment. Similar to the style and purpose of haiku poets, Kawabata is able to bring nature, weather, setting, and mood to life in a very tangible and dense way.

His words carry weight but they also flow and flutter playfully. He has a simplicity to his writing but a density to his tone. To marry all of these disparate feelings in such an effortless way is the reason why he was named a Nobel Laureate.

Born in Osaka in 1899, Kawabata was far more of a Japanese traditionalist than his contemporaries (Oe and Ishiguro), with much of his writing circling the themes of death and loneliness, as well as having a frequent discussion with the relationship between Japan and the influence that the West has had on his home.

Kawabata’s most famous novel, Snow Country (1948), famously took 12 years to complete and tells the story of a lonely geisha who lives in an isolated onsen (hot spring) town and her love affair with a man from Tokyo.

As expressed in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, at his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Kawabata said that, through his writing, he had attempted to beautiful death, and to seek harmony among man, nature, and emptiness.

If you liked this list, you may enjoy: Five Female Asian Writers to Move your Heart and Mind