Indonesia, Asia’s largest archipelago, is one of the world’s most ethnically, religiously, and culturally diverse countries.

It is a place called home by every kind of human being. And so, Indonesian novels, stories, and poems offer readers that same kind of diversity and excitement.

The Indonesian novels, stories, and poems found here do not encompass the entire literary scope of Indonesia, but they do offer a few wonderful places to begin reading Indonesian books in translation.

Here, you’ll find some of Indonesia’s best writers, poets, and translators.

Indonesian Short Stories

Here are two collections of Indonesian short stories, one of which paints a beautiful picture of Jakarta by the hands of ten of Indonesia’s best writers; the other puts a feminist horror twist on classic Indonesian folk tales.

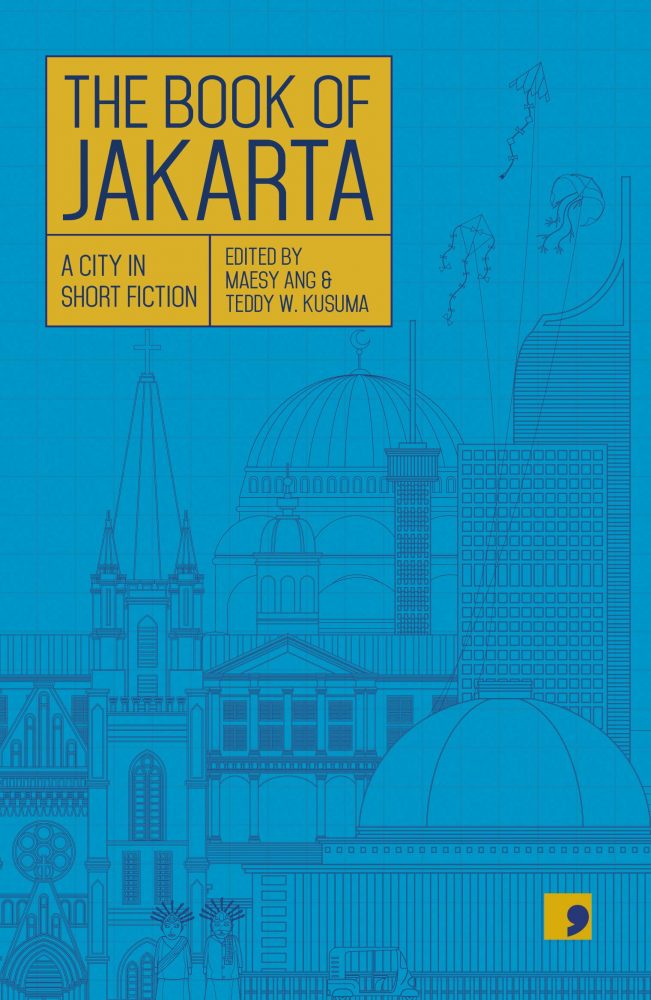

The Book of Jakarta: A City in Short Fiction

Edited by Maesy Ang & Teddy W. Kusuma

Jakarta is likely the most multicultural city in all of Asia, and a quick read of the introduction to The Book of Jakarta serves as a good lesson in why this is. Following that up with a read through the ten stories that make up The Book of Jakarta allows you to see all sides of life in Indonesia’s capital city.

The diversity of Jakarta can be seen in its religions, cuisine, languages and dialects, ethnicities, politics, and more. Reading a collection of stories by writers of different ages, genders, and ethnic backgrounds — all of whom are writing about Jakarta — is like taking a cultural, geographic, and historic tour of the city.

A read of the book’s introduction (written by its editors, Maesy Ang and Teddy W. Kusuma) is enough to be provided with a detailed and enlightening history lesson about Jakarta; one which even speculates about the city’s future.

In 1998, Indonesia underwent a revolution, when the dictatorship of President Suharto’s New Order was topped. This New Order came about after World War II and the relinquishing of control from the Japanese Empire. Prior to Japan’s control, Indonesia had been occupied by almost every great European power at some point and for some time.

The cultural and political history taught to us by this introduction alone is illuminating, and the book has yet to even begin. What follows the book’s introduction is a deep dive into the city of Jakarta from the perspective of a diverse group of writers and translators.

If you want my advice, the final story in The Book of Jakarta — titled A Day in the Life of a Guy from Depok who Travels to Jakarta, written by Yusi Avianto Pareanom and translated by Daniel Owen — is actually the best place to start.

This final story gives readers a funny, fascinating, and frustrating tour of the city. It follows an ordinary day in the life of a suburban man who works as a landscape gardener. He takes the train into the city to sort out a visa at the US embassy, only to find that he has forgotten his passport.

While in the city, our man takes a bus, a few taxis, and another train as he runs errands, meets friends, chats with strangers, and navigates the complex, unpredictable routes of Jakarta. This story introduces us to Chinese-Indonesians, Arab Indonesian Muslims, friendly coffeehouse owners, misogynistic cab drivers, punk kids, and more.

A Day in the Life of a Guy from Depok who Travels to Jakarta is a true tour of the city, both geographical and emotional, as we experience all the frustrations and difficulties of physically navigating city life. We laugh, grit our teeth, and laugh again right alongside our protagonist as we live a normal life in Jakarta.

The religious and cultural diversity of Jakarta can most clearly be seen in two of its most claustrophobic stories: The Aroma of Shrimp Paste by Hanna Fransisca (translated by Khairani Barokka) and Haji Syiah by Ben Sohib (translated by Paul Agusta).

The Aroma of Shrimp Paste is a sharply-written Kafkaesque tale of nonsense bureaucracy set in an immigration office. Our protagonist is a Chinese-Indonesian woman who is patronised, lied to, and led in circles by the people around her for several hours. It’s a story that is, in true Kafkaesque fashion, equal parks darkly funny and deeply frustrating.

The Arab-Indonesian world, on the other hand, is shown to us by Ben Sohib in Haji Syiah, a story which tells the story of the titular Haji Syiah, a Sunni cleric who works to reform the lives of two local drunks, Faruk and Ketel. The story is told through hearsay and with humorous insights by other clerics in the neighbourhood.

In the introduction to The Book of Jakarta, editors Maesy Ang and Teddy W. Kusuma remark on the city’s doomed future, with climate change rapidly dragging the city down into the depths. Half of Jakarta will likely be underwater by 2050.

This very real, very near future is explored in The Book of Jakarta’s shortest story: Buyan by utiuts (translated by Zoe McLaughlin). Buyan tells the brief tale of a woman in a future Jakarta who is stuck inside a self-driving taxi, headed for the drowned half of the city and worried for her life.

Buyan is a hilarious story that approaches the frightening future of the city with joviality. Instead of warning us about this calamitous future, it instead shows us a very possible, very ordinary situation that could easily occur to any ordinary person once that calamity finally happens.

Like every other book in the A City in Short Fiction series by Comma Press, The Book of Jakarta is a collection of short Indonesian stories that, together, serve as a kind of literary mosaic of the city of Jakarta.

What that mosaic most brightly shows is the electric diversity of Jakarta. Many of these stories have so little in common with one another, serving to show just how ethnically, religiously, and politically varied Jakarta is. This city contains multitudes and it is beautiful.

Read More: 7 Books of Arabic Short Stories

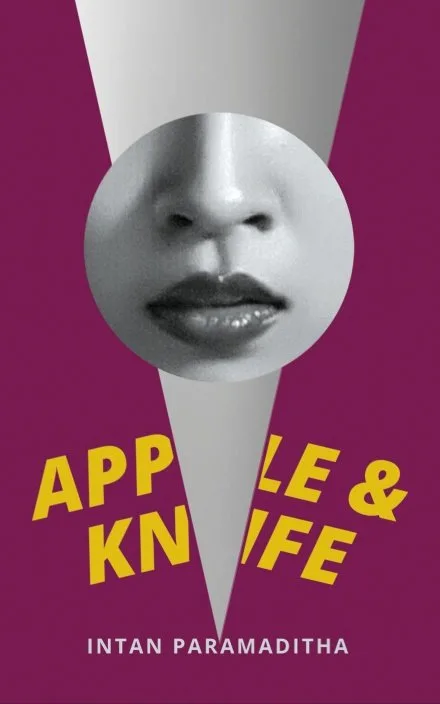

Apple and Knife by Intan Paramaditha

Translated by Stephen J. Epstein

Most of us know that every country and culture has its folk tales and fairy tales, and most of us know that these often horrific tales of punishment, death, revenge, and tragedy have been muted and twisted into happy stories by Disney, and in Japan’s recent children’s anime Yokai Watch.

But how can we take the folk tales that our ancestors grew up with and translate them faithfully and imaginatively to fit the modern world, without losing the horror?

Intan Paramaditha has done not only this, but has also put a wonderfully feminist, gothic spin on every single tale, making it all the more relevant and poignant in our modern day.

She has also recently published a choose your own adventure narrative which is just as unique, challenging, as unsettling as Apple and Knife.

Apple and Knife is a collection of fairy tales, predominantly set in and around her home of Indonesia, which take inspiration from local Indonesian folk tales with a few other (and some recognisable) fairy tales from the other corners of the world thrown in.

Before we discuss the details of what makes this book such a triumph, uproarious applause, I insist, must be lauded on Stephen J Epstein for his astonishing translation skills here.

Prophecies and poetry here are translated with such confidence and skill that it is easy to forget that these stories were translated at all. Epstein is a credit to his craft, and budding translators should pay attention: this is how you translate.

Reminiscent of UK poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy’s poetry collection, The World’s Wife and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, Paramaditha has collected stories from her native land, and the world over, switched their focus to that of a modern woman, and added a theme or moral that resonates well with us today.

The result of this staggering effort is astonishing. Every tale in this book is dark (at times darkly comic, at others darkly tragic) and leaves the reader, lacking any catharsis, with a need to put down the book and collect their thoughts for a moment.

These stories allow us a chance to re-evaluate our own modern myths and values: how men treat the women in their family; the ways in which we experience and talk about women’s issues (emotional, psychological, and physical); the ways in which our religions affect our outlook on sex, marriage, and gender.

Taboos and faux pas come under fire, and history is held under a microscope, all while under the guise of a simple fairy tale. The power and intelligence of these tales cannot be understated.

These female-focussed stories force to the surface questions that both men and women have either always wanted to ask, or never thought to ask before. But every one of these heavy themes — such as abortion and menstruation — is delivered as a ghostly, bloody, horror story.

Apple and Knife is a book that does more than push boundaries; it breaks them down completely. Patriarchal traditions, Muslim values, and cultural superstitions are all questioned and held accountable here.

Every story is at once a garish and nasty folktale to be enjoyed and gasped at, but also serves as a reminder to women that they are strong and fierce and dangerous. And that we men should take stock of our privileges, and the boxes we force women into, whether we are aware of it or not.

Indonesian Novels

These are three of the finest Indonesian novels by three outstanding Indonesian writers, translated by some of the best in the business.

Birth Canal by Dias Novita Wuri

Translated by the author

Birth Canal is an Indonesian novel presented as four interconnected tales, each of which centring around the difficult, dynamic lives and experiences of Indonesian women from World War II to the present day.

The first story is told from the perspective of a nameless man in Jakarta who has spent his life suffering in unrequited love with a dear friend named Nastiti, who, one day, suddenly vanishes.

The second story follows Nastiti’s mother, whose own mother was used as a “comfort woman” and given the Japanese name Hana by the Japanese military during World War II. She has travelled to Amsterdam to tell her mother’s story to an academic.

The third story centres around Hana’s Japanese husband, who was tormented by the war, suffered PTSD, and tormented and abused Hana in turn.

The fourth and final story returns us to the present day, and follows Dara, the girlfriend of the nameless man from the first story. Dara has since married someone else, whose work took him to Osaka, and there she is attempting to acclimatise, learn the language, make friends, and have a baby.

Birth Canal spans many lives and many years; it explores the complex and murky ways in which we affect one another, and more specifically how we often make each other suffer without ever coming to terms with that fact.

Blending war, politics, and tragedy in powerful ways, Birth Canal is an ambitious short novel covered in scars.

Buy a copy of Birth Canal here!

The Wandering by Intan Paramaditha

Translated by Stephen J. Epstein

The Wandering is a dense Indonesian novel of branching paths inspired by the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure books of old. But while those books were fantastical, and written for kids to experiment with their own imaginations, The Wandering is a story of migration, of searching the world for happiness and hoping that it will be found over the next page (or if you turn to page 42).

The narrative in The Wandering is written in the second person, with all the action directed at ‘you’, the reader. But you are no blank slate here; in fact, you’re a fairly defined protagonist.

‘You’ are a woman, aged 27, Indonesian, and living in Jakarta as an English teacher. When the Devil comes to you, you lash him to your bed and make him your lover for a few weeks until, eventually, you use him to gain access to the wide world.

The Devil provides you with a pair of red Dorothy shoes and magics you away to New York. Specifically, a cab on the way to JFK, with a ticket for Berlin.

You are disorientated and, when you arrive at the airport, you realise one of your red magic shoes is missing, and you must make your first choice: continue on to Berlin, return to NYC and find your apartment, or report the missing shoe to the police. Each thread leads you to more threads, and there are fifteen possible endings to your story.

The Wandering does an obscene number of things well. It’s a strange tale that blends tongue-in-cheek magic realism with very grounded and anxiety-riddled choices and pressures.

This is even reflected in the endings, some of which involve the re-emergence of the Devil or a tussle with the presence behind a magic mirror, while others peter out into a mundane but satisfying and ordinary resolution. At its core, however, it is a book about restlessness.

The choice of title for this novel, The Wandering, is pitch perfect. While it might seem at first to be a book about travel (where do I fancy flying off to now, with my new-found freedom?), it is in fact a tale of belonging. It’s a novel that asks you to question what, exactly, happiness is.

It posits that happiness is not something that cannot be chased nor found. Instead, our protagonist must wander. She wanders the United States, she wanders the streets of New York, she wanders over to Europe and back again, and at no point is true happiness or satisfaction found.

The Wandering is a deeply affecting, intensely personal novel that uses its experimental method of storytelling to worm its way into your very bones. Even though our protagonist is a well-established character whom you happen to, at least to a point, embody and control, you still desperately feel for her.

The novel wants us to know that happiness and satisfaction is not so easily found, that answers are hard to come by, and it forces us to realise that actively, rather than passively.

This is not a narrative that we ingest. Nothing is told to us. Instead, it is actively experienced through the choices we make. It builds a frantic anxiety that cannot be shaken, and by the time we eventually reach a decent enough ending – one that might lack pomp and splendour but is good enough – we have to feel content in that.

The Wandering is an interactive adventure like no other, one which leaves you feeling chilled and frightened and alone. It asks you to, please, consider how you go about searching for answers and happiness. It wants the best for you, but it admits that the best is hard to find.

Man Tiger by Eka Kurniawan

Translated by Labodalih Sembiring

Although fairly slim, on paper Man Tiger almost begs to be labelled a work of magical realism; a generational tale set in an unnamed town in the tropics teeming with lusts and dreams, violence and loss, spirits and folklore.

Littered throughout are references both allegorical and literal to Indonesia’s colonial past and economic struggles. Kurniawan lived through the brutal and repressive Suharto dictatorship which saw many books banned and many writers imprisoned or disappeared.

Fertile ground indeed for the kind of socio-politcal satire of Salman Rushdie or Gabriel Garcia Marquez; and, after all, the English translation is published by Verso books, an imprint better known for works of leftist economics and Marxist theory than literature and fiction.

However, the book’s appeal and charm lie in the way it flouts the conventions of magical realism whilst refusing to shrug off the genre completely.

Kurniawan did not grow up around books; in his childhood he’d listen to his grandmother tell stories and plays on the radio and then as a teenager he read action and horror comics bought from street vendors.

It wasn’t until entering university that he became exposed to more conventional literature, including Western and Latin American works. All three influences make themselves known as Man Tiger unfolds.

The oral narratives of Kurniawan’s youth are echoed in the way that many of the novel’s key events are given second hand as reports or gossip and the gruesome details of the murder at the heart of the story could be taken from the pages of a teenager’s comic book.

But after the initial shock and excitement of the bloodshed Man Tiger gives way to a longer and more reflective exploration of the past events that lead to the crime, and it’s this history that constitutes the bulk of the work.

In Man Tiger Kurniawan shows a great restraint in his handling of language and use of literary devices, limiting himself to a few expertly placed images that are seamlessly woven into the world of the novel rather than existing as mere linguistic showboating on the page. Indonesia’s bloody past is given to us at the scene of a savage murder.

The history of Japanese colonialism is encased in actual historical relics — the rusty samurai swords dotted around the town — one of which is dragged along “scarring the ground with its tip” as a reminder of the lasting damage of colonial rule and its capacity to still cause harm in the present.

Kurniawan’s metaphors and devices have a solidity to them, a palpable presence in the space of the novel. It’s this groundedness, this sense that everything in the novel possesses weight, that sets Man Tiger apart from Midnight’s Children or One Hundred Years of Solitude.

In those works the writers employ rich and vivid sensory descriptions, the effect of which is to overwhelm and knock the reader back and out of their usual centre of perception enough that a veil of mysticism can be draped across the gap between the world and our perception of it, rendering the events of those stories extraordinary and fantastical.

Man Tiger takes a different approach, for whilst we are still immersed in Kurniawan’s tropics overgrowing with palm trees, cassava and papaya, the magical and the supernatural always make way for reality and are pushed aside before it.

For all the bustle and busyness of the scenery and surroundings we are always anchored down by the everyday: school girls queuing up for breakfast fritters worry about being late for class, the protagonist Margio as a child riding a wagon across a country everywhere bursting with exotic sights yet ultimately more concerned with his marbles and trading cards.

Later, an adolescent Margio trying to navigate a blossoming romance with a local girl. Even the tigress spirit alluded to in the title is described as being “like a giant domestic cat”.

Always we are slowed down to the pace of day-to-day life. Rituals involving animal sacrifice are described more in terms of the logistics of their preparation rather than their occult aims; our attention rests more on the cigarettes smoked by gravediggers rather than the occupants of said graves, even when the grave site appears to be afflicted by a curse.

The structure of the novel itself is a process of demystifying and explaining away the otherworldly, beginning with a shocking murder and talk of animal possession before a chapter-by-chapter unpacking of the history of the families involved and their small tragedies, simple lives, lusts, infidelities and desires.

In the end, the domestic violence at the centre of Margio’s home life is given far more central a role than the murder or the lingering effects of past colonial violence.

And on the subject of violence, Kurniawan makes sure not to let it become too divorced from reality, making sure that what gore is present is tied to the earth in ways that ensure we remember that, sadly, this kind of carnage can be a very real part of the world.

There are “clods of flesh scattered all over the floor, like spilled spaghetti sauce” and a severed artery “dangling like a cable in a shattered radio”. He is quick to tell us that these visceral scenes are more terrifying than ghosts and nightmares, “more brutal than any horror film”.

There is a sense that, between the frequent banality of life and the moments of tragedy and horror that can punctuate it at any time, there is something precious to be found in the flow of normality.

It’s too cheap and easy to finish by writing something to the effect that Kurniawan is putting the real into magical realism; but I will say that, with Man Tiger, he has given us a work that remembers the capacity of fiction to bring us back to the world; it captures the moment when we are shaken from a daydream as if by a sudden shout or, more appropriately, a roar.

(Written by Frank Jayne).

The Majesties by Tiffany Tsao

The Majesties certainly launches itself out of the gate with a first chapter that promises an intense thriller of a tale. Protagonist and narrator Gwendolyn has always been inseparably close to her sister Estella — they even went to the same college at the same time — but now she finds herself in a coma after Estella poisoned the shark fin soup at an enormous family gathering, murdering 300 guests.

The sole survivor being Gwendolyn who, now trapped in her own comatose mind, has nothing to do but unravel the threads which led to this point. What moments in Estella’s life led her to this decision to kill 300 people, most of which were her own family?

Every single moment of The Majesties is written and narrated with absolute control. Not a beat is skipped or misjudged, which is what makes it such a finely tuned thriller.

Except The Majesties isn’t entirely concerned with being a thriller. As I said, this novel is not a typical whodunnit murder mystery, with a plot that hinges on finding answers – even though that is arguably still the driving force of the plot.

Instead, this is more a novel about family and what being part of one ultimately does to our psyches. Consider your own family and the scars they have left on you throughout your life, whether intentional or not.

For Gwendolyn and Estella, born into a vastly wealthy empire of a Chinese-Indonesian family, their scars run deep. While I, personally, have little love for the troubles of the rich, Tiffany Tsao made me care immensely for these two sisters; trapped as they are in a world they didn’t choose.

Gwendolyn, now in her early thirties, made the choice not long ago to leave the family alone – to separate herself and set up her own business: Bagatelle. It’s an unsettling business, to be sure.

Using a serum made from cordyceps (parasites which burrow into the brains of insects) Bagatelle sells jewellery with insects encased inside, frozen by the serum.

Gwendolyn begged Estella to join her in her venture, but Estella refused, choosing to stay close to the family. The strain this disagreement places on them forms a large motivation for many events of this story.

The story itself is told across an entire lifetime split in two. We are frequently thrown from period to period as our comatose narrator rushes to fit two puzzle pieces – found in two different decades – neatly together.

We travel through both time and space to the beginnings of Bagatelle in Jakarta; further back to their years studying together in California; forward again to Estella’s rocky marriage.

Gwendolyn’s ability to tell Estella’s story with so much detail and clarity is enough to demonstrate their closeness; their need for one another. In fact, in many ways, this is Estella’s story. Gwendolyn is, after all, desperate to understand what led her to become a mass murderer, and to want to take Gwendolyn herself down with the family.

This flitting between continents and time periods could so easily fall apart or become disjointed at the hands of a less competent writer. But Tsao, not for a single moment, loses control of her narrator and her place in the story.

While we are being rushed hither and yon, and we might feel a lack of control, we can rest easy knowing that Tsao has a firm grip on the story’s reigns.

This is an expertly crafted tale which, even though it moves backwards and forwards through time, has an emotional progression that only moves in one direction as Gwendolyn, the story’s puppet, comes to understand the existence of her strings. It’s fitting, looking at it this way, that Estella refers to her sister as Doll.

Looking at The Majesties through the lens of a thriller, all of the necessary tropes and methods are in place: Chekhov’s gun is loaded; metaphors and foreshadowing are heavy-handed but never awkward; dominoes are set up and breadcrumbs laid down with delicacy and decisiveness.

But all of this is easily forgotten due to Tsao’s deft sleight of hand as she encourages us to put all of that aside – to forget that this is a thriller – and instead directs us to pay attention to and care about these sisters and the scars they’ve collected.

Gwendolyn and Estella are not easy to love. Sometimes you’ll find yourself siding with one over the other, only to switch sides later.

Sometimes your heart will ache for them and their lot in life — one of entrapment and family games — while at others you might think how much you would prefer their issues, their drama, over your own. But all of this guarantees us protagonists who are fallible and human.

Indonesian Poetry

Here is an Indonesian poetry collection by a vital figure in the world of queer poetry, full of heart and soul and love.

Sergius Seeks Bacchus By Norman Erikson Pasaribu

Translated by Tiffany Tsao

Sergius and Bacchus were fourth-century Roman soldiers. In secret, they were also Christians. They would pray in isolation but were eventually found out and executed for their faith.

Parallels between their secrecy and that of so many queer communities across the globe has turned them into something of a symbol for queer visibility.

In this intimate collection of queer poetry, Norman Erikson Pasaribu has taken the names of Sergius and Bacchus – and what they represent – for his collection’s title, phrasing it as Sergius Seeks Bacchus perhaps as a reflection of the repeated theme found in the book’s pages: that of uprooted unrest, searching, longing. Seeking.

In an interview with Electric Lit, Norman himself discussed the counterparts of his own writing and that found in Christian history, as well as his own connection with religion.

He recalls: “I attended my old office’s Easter mass, and the priest, who was a Toba-Batak man, threw homophobic slurs during his sermon.

I ended up excusing myself and cried outside the hall. After that, the desire to go to church gradually diminished.”

Despite this tumultuous relationship with religion, the impact it has had on Norman and his writing is painted widely across his poetry. He decries its ability – its willingness – to abandon queer people, to make pariahs of them.

In the three-part poem Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso he remarks of a queer man in Paradise: “See him here, with all the Lost and the lives never His.”

In Theophilus, a poem named for the ‘Friend of God’ said to have written the Gospel of Luke, he retells the story of Creation as a man seeking basic human needs: “The sun’s so strong. I’m parched.” Each time, God delivers, but when the man remarks, “It’s so deserted. I’m Lonely,” God says nothing, and a voice says, “You will never be with the someone who loves you most.”

There is a wider breadth to the wanderings of these poems, too, as they concern themselves with the broad strokes of love as it exists today.

The awkward and rigid binaries of heterosexual relationships are examined through a piteous lens, and the secrets of frightened, closeted gay married men are exposed.

A cynicism is raised against the state, in a quintessential Kafkaesque manner, as Norman jokes at how governments and industries may find a way of turning emotions, feelings of love, and life experiences into commodities.

In a darkly funny move in the poem Lives in Accrual Accounting, Yours and Mine, he pokes at how the analogue fluidity of life and its moments both light and dark might be measured in a digital, tangible way. Not felt but known and catalogued.

Much of the poetry in Sergius Seeks Bacchus is freeform, unrestrained by rhyme and metre as, perhaps, the lives of the queer people of Indonesia should be allowed to be.

Much of what we read here are stories which play with perspectives, from the omniscient narrator who knows the hidden thoughts and motives of secretive people, to the second-person-driven stories that force the reader into the shoes of an unlucky innocent that might, if the dice had been rolled differently, be them.

In an interview with us, translator Tiffany Tsao remarked on the importance of carrying forth the artist’s tone, emotion, and intention: “Finding Leo was immensely difficult, even though it’s one of the shortest ones! It took me months to figure out a version of the last two lines that Norman and I were happy with.”

Working together with the poet himself proved, unsurprisingly, key to delivering a faithful and workable translation.

Translating poetry – an art form that works by playing on words and their meanings, their sounds and their lengths, the ebb and flow of their shape on both the page and the tongue – is arguably the most difficult kind of translation.

But Tsao went to the furthest lengths to ensure Norman’s heart remains tacked to each of these poems, whatever language they are read in. And that is certainly felt, through and through.

In Indonesia, queer people face prejudices and dangers. It is also a nation predominantly Muslim, but with a felt Christian and Catholic presence.

Queerness and religion, the way in which these two interact, wage war, and cause heartache when mixed — this is all felt with both deep sorrow and a flighty wit in these poems.

Norman has the ability to smile and laugh in the face of adversity, to occasionally see the light shining between the gloomy, dark trees.

But there is still fear and nervousness, the need to look over one’s shoulder when risking being who they simply are.

Existence is difficult, and it is made more difficult by cruel external forces forged by other human beings. Through Sergius Seeks Bacchus we feel all of this. Sometimes we laugh, and sometimes we cry.