“Let’s face it, manga has always been lame! . . . But it’s okay that it’s lame.”

— Inio Asano, “A Tour Through Inio Asano’s Workplace”

In one way at least millennials are lucky: we were the first generation in the West for whom imported Japanese culture was completely unremarkable.

Though it comes from a world away, Japanese art speaks so readily beyond its borders, in part I think because Japan has been the site, in the last century, where all the tensions of our common modernity have played out at whiplash speed.

Japan is where immovable East met unstoppable West, where tradition and custom meet the jagged new. Japan is also, consequently, and most interestingly for someone like myself (a child who grew up on Japan’s pop culture; an adult who has grown into its grown-up literature) somewhere where the line dividing high and low art is very sharply drawn indeed.

In Inventing Japan, Ian Buruma describes the moment after Japan’s surrender in 1945 when these long-standing divisions in Japanese cultural life opened wide. In the aftermath of the war, explains Buruma, the country stood at the brink of the great 20th century dilemma: just how modern, how American, was it to become?

Why is Goodnight Punpun a masterpiece?

On the one hand, gum-hungry children trailing U.S. G.I.’s through the ruins of their old cities and “pan-pan girls” (prostitutes) “dressed in cheap approximations of American fashions” were the early “pioneers of American commercial culture.”

Japan’s “intellectuals,” on the other, were “disdainful” of this ingratiation, which would see them become “a mere cultural . . . satellite of the United States” (Christopher Harding, Japan Story). Squaring up to the headache on the horizon, they began instead to cultivate what Buruma calls a quiet “air of nihilism.”

This sharp division would characterise the literary arts in Japan for the following century. As manga (Japanese comics) exploded across the post-war landscape in a burst of ebullience and colour, writers of a more sophisticated literature have, as a rule, favoured introspection, understatement, and a distinctly unAmerican unshowiness.

The major works in the Japanese canon tend to have little of the large, diverse casts, the dramatic romance, or the technological sublime that characterises Japan’s best works of popular fiction. Indeed, according to Alex Kerr, this is precisely why manga has been so successful: because it is the only art form that can “do justice to the more bizarre extremes of modern Japan.”

Though there are, of course, exceptions, such as Haruki Murakami, whose work blends the high- and low-brow and has achieved a similar success in the West, he is something of the exception that proves the rule: “accused at home of being neither truly Japanese nor truly literary” (Harding).

The stark division between Japan’s popular culture and its national literature is thrown into especially sharp focus by the ways in which Japanese books are translated, marketed, and managed for the English-speaking West.

The fact that I can predict with some certainty that you—you, a sophisticated reader of world literature in translation—have very probably never heard of the mangaka Inio Asano or his masterpiece Goodnight Punpun is symptomatic of Western literary culture’s own manga problem.

I discovered Asano’s work myself entirely by accident, when his short book A Girl on the Shore—a shatteringly sad, smart, erotic story about young lust—was on display one day on the bottom shelf of the Comics section in Glasgow’s biggest library, sandwiched inappropriately between The Unending Adventures of X-Men and an illustrated children’s book about warrior mice.

One can’t really blame the librarians for the miscategorisation, since Vertical Inc.’s own blurb for Girl is laughable: “Maybe Keisuke wants something more than a kiss from the fair Koume… And this will all transpire before high school exams!”

The misjudgement is endemic. Girl is one of the smartest and most moving books about being young that I’ve ever read but, like all of Asano’s work, it has never been seriously reviewed. Outside of comic book circles its author might as well not exist.

The problem is that Asano has gotten locked now into this awkward, liminal place. You haven’t heard of him at all because his work is released into an airtight publishing bubble, yet no one in that bubble knows quite what to do with a capital-A Author of genuine literary art.

It is telling that though Goodnight Punpun’s Touch-up Artist and Letterer (Annaliese Christman), Designer (Fawn Lau), and Editor (Pancha Diaz) are all credited, the actual individual responsible for translating Asano’s wordy masterpiece is not mentioned anywhere in any public-facing VIZ documentation. (Imagine Dostoevsky’s Pevear, Volokhonsky, or McDuff getting the same treatment!).

Read More: Japanese Literature in 12 Genres: Where to Get Started

Indeed, VIZ Media—the publishing monolith responsible for what seems like pretty much most major manga series—is so at odds with the typical publishers’ idea of the Author that they sort their enormous manga library by alphabetising all the books’ titles, not by the names of the people who wrote them. (!!!).

I love a lot of VIZ’s work, and it’s important to clarify that pointing out the existence of this ‘high-low’ divide does not necessarily constitute an automatic value judgement. A lot of manga are fun and affecting and brilliant, if not always cerebral.

A lot of highbrow literary fiction is intelligent and serious and as dull as a pair of chewed spectacles. There is room in the world for both, but there is a line between them. (When one Googles Asano and finds pictures of manga fans at conventions cosplaying as Goodnight Punpun’s two main characters, one a suicidal victim of life-long abuse, the other in the throes of a profound ontological crisis, it’s hard not to feel like that line is being crossed).

So though I’d be lying if I denied that I first discovered Asano’s work because A Girl on the Shore’s cover was pretty and its content excitingly X-Rated, it is my privilege as someone who slummed it on your behalf to get to tell you now what no one, apparently, knows. Inio Asano is an unsung giant of world literature, Goodnight Punpun is the Brothers Karamazov of Japanese fiction, and he and it both absolutely deserve our attention.

(ˇ⊖ˇ)

I’ve recommended Goodnight Punpun to smart people before, and I’ve noticed that they always get this look in their eye when I bring out The Brothers Karamazov. But, other than the small fact that Punpun isn’t 400 pages too long, the comparison between it and Dostoevsky’s own masterpiece is completely apposite.

They are both books of their moment. As the Karamazov family is all cracked, a distillation of the poison that beats through the blood of Dostoevsky’s Russia, so the Onodera family embodies the spiritual dysfunction laced through Japan at the turn of the millennium. (“Cracked,” by the way, is McDuff’s great phrase, and much better than Pevear and Volokhonsky’s “Strains,” Garnett’s “Lacerations,” or Avsey’s “Crises.” Translators matter, huh?).

Punpun’s mother is a broken, faithless fool, who like Dostoevsky’s Fyodor hides her vulnerability behind a vulgar mask. Punpun’s Uncle Yuichi is a millennial Mitya, a self-hating moralist driven to madness by the beauty of a young girl he nobly hates himself for wanting. We see Smerdyakov’s empty nihilism in Seki, Alyosha’s sickly purity in Shimizu, Katerina and Grushenka’s beauty and pride in Sachi.

It is a mark of Asano’s genius that though Punpun expanded to nearly 3,000 pages during its serialisation it never feels unplanned or weighed down.

This is partly because each characters’ story is full of Shakespeareanly intense and well-told drama, but also because there are clear controlling ideas—profound, Dostoevskyan ideas about human wretchedness and philosophic exhaustion, about shame and “the pain of being forgiven,” about what it means to grow up and live fully when the world is coming to its end—that govern every element.

Punpun himself is anxious and lovelorn and corruptible, a fundamentalist with nothing but the dream of a girl to believe in. In Goodnight Punpun Asano spins one boy’s story into an epic that contains a whole era, an epic about all the different ways we who live now are racked by fear and faith and love.

Read More: Books for People who Love Japan and Cats

In a landscape of big literary fictions at the turn of the millennium, in which what passes for universal grown up themes is solipsism, disaffection, and a robotic miserable lovelessness, it’s hard to describe just how thrilling it is to read something that’s literary and smart but still about recognisable human beings.

Perhaps this is because, as a rule, manga tend to focus on young people drunk on feelings — as opposed to adults, who in literary fiction get drunk on everything else — and Asano belongs without embarrassment to that tradition.

But in a form that typically relies on speech bubbles saying what they feel and explaining what they know (“My father never needed me . . . but now he’s built a robot that needs me?” [Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Neon Genesis Evangelion]), Asano elevates what might seem like childish melodrama in other, clumsier hands, to profoundly serious art.

And it is art in every sense. Goodnight Punpun is novelistic and brilliantly written but all this is only half the story. For almost seven long years, week after week after flawless week, Asano had to draw the whole work too.

To understand what makes Goodnight Punpun such a landmark work, it’s important first to understand that there is something like a spectrum of drawn styles across the manga tradition. At one end of this spectrum you have the familiar anime image: the larger-than-life eye sockets, the mouths on one side of the face so characters can speak without their cheeks or chins moving.

It’s the whimsical style of Pokémon or Sailor Moon or whatever else you remember from Saturday morning TV, all clarity and concision because it’s quicker (and therefore cheaper) to animate.

At the other extreme is a kind of hyper realism. Characterised by complexity, detail, and white space overrun by shadows, this style emerged in manga with the Gekiga Workshop in the punk 60s as the answer to post-war manga’s “childlike,” “flowing lines and expansive, fantastic stories” (McCarthy, A Brief History of Manga).

It’s no coincidence that this style today is the paintpot for adult horror, for Junji Ito’s creepy spirals or the corded zombie muscles in Kengo Hanazawa’s I Am a Hero. Aging and sickness and death are, after all, the ways we—who were once unblemished and young—wither into detail.

Asano has a gift for detail you have to see to believe. At a time when manga are being wrung out by punishing deadlines and an oversaturated market—increasingly you see the computer-generated image, the cut+paste background—Asano’s style has gone almost belligerently the other way. The bare mechanics required to produce Punpun’s thousands of pages are staggering. There isn’t a single image that feels rushed.

His method is one that Naoki Urasawa describes, in an interview with Asano, as “not using the computer to cut corners or make things easy. That’s almost painfully clear.” The real-feeling shape of Asano’s settings, his characters’ unusually realistic anatomy, their clothes like scraps of the photoreal background they’ve wrapped themselves up in: it’s all pen-point, pin-point, pixel-perfect draughtsmanship.

But this, on its own, is only so interesting. What makes Punpun so important is that it is uniquely stretched between manga’s two ways of seeing the world. While Asano’s backgrounds and characters are photoreal, for example, there is something special about the way he draws faces.

His characters’ eyes flirt with manga-bigness. The lines of their mouths are delicate and sometimes ink-brush thin. Their skin except for flushed cheeks is the spotless colour of the paper they’re drawn on. It’s a visual juxtaposition most akin to Shigeru Mizuki’s work in Showa, a manga history of Japan that mixes fact and subjectivity, real photos and the cartoon Mizuki who relives the history those photos describe.

Asano’s style is strange though, less jarring, as if his characters are impossibly as real as the backgrounds they stand in and more manga-beautiful than they should be.

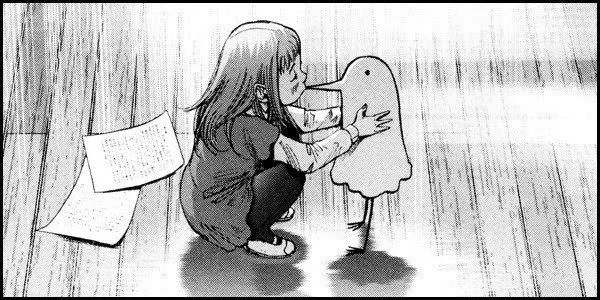

The most extreme example of this effect, of course, is Punpun himself, who I’ve tried not to mention—since it’s all anyone talks about—is a cartoon bird. The fact that Punpun is a bird, doodled like a stick-child playing dress-up as a ghost, is not a literal thing but for our eyes only.

So Punpun stands on a school desk, for example, to be at eye-level with his friends and the height he would be if drawn realistically, just as he doesn’t have a schoolbag like the others but more of a messenger pigeon’s pouch, too small for school-books.

The consistency of the cartoon-logic allows that we can always half-translate what’s on the page and find the ground that roots the visual metaphor, and boy does it work. The cartoon is paper-flat and unreal-looking but what we’re actually seeing is what’s behind the character’s bird-shell: that small scared soul, floating like the ghost that haunts the space he really stands in.

To watch Asano’s characters exist on the page is to experience something genuinely profound. It is to re-experience the comforting and necessary fiction that we all live in everyday: that people are not just the sum of their details but hearts that beat, souls beneath the skin, imaginations other than your own.

Read More: Books to Read Before Visiting Japan

The kind of reviews Asano gets focus on the comic’s formal gimmicks to the point of tragedy. It is an insult especially to Goodnight Punpun, where Asano’s style is so fundamentally integral to the story he is telling. You will start to notice when you read, for example, how the kids in the first book are, like Punpun himself, all heart-hookingly manga-cute, while the hard-lined adults seem slightly . . . off.

Where the kids have clean-lined manga smiles—not a photorealistic smile, but a smile as you feel it when you see it in others—the adults at their school have clearly delineated individual teeth that in detail look too many and too grossly diagrammatic to fit inside a manga mouth.

Both kids and adults have slightly enlarged eyes, but where the kids’ are bright and wide the adults’ are sagged and strabismic, their faces hung like gormless masks. The adults are, in other words, ugly, and all the creepier for being so childlike in their actions, so cartoonish.

The nostalgic, manga dream-scape to which the kids of Goodnight Punpun belong is so sweetly drawn that you can’t help but be seduced by its beauty, but it is necessarily a prelapsarian dream. Asano draws from one end of the mangaspectrum to the other but his characters belong to it.

The adults are creepy because their behaviour is childlike, their eyes gross because they are manga-big like the kids’. The metaphysical structure of Asano’s world is embedded in his aesthetic: the very qualities that must once have made his characters cute are what twist most out of shape in adulthood. The Fall is built in. The children are beautiful in the beginning, but they won’t be forever.

It’s frustrating that though VIZ have conscientiously rated the books “M for Mature” their copy is still couched in terms of their main demographic. “Compelling tales of teenage angst” is one way to describe Goodnight Punpun, but it’s a book about “teenage angst” the way The Brothers Karamazov is “a novel about children and childhood.”

Who relying on VIZ will ever know that they’re missing one of the turn of the millennium’s great religious epics? Goodnight Punpun is not just about young adults but about what it actually means to be young, to be innocent, and to stand on the precipice of experience. It’s about what it means to reach that age when you begin to fall in love. It’s about what it means to Fall.

(ˇ⊖ˇ)

If there is a shape to the protagonist Punpun’s own life and to Goodnight Punpun as a whole it is bound by the Fall: by sin and shame and by Aiko, the girl that Punpun loves. She is the stuff that manga dreams are made of.

She’s the school’s cute new girl in volume 1 with the big eyes and the missing tooth, the girl who shares Punpun’s only ever first kiss, the girl who needs saving from her secret life, whose sadness seems to offer Punpun everything because she would need him back. It’s hard not to fall in love with her with him. Asano’s endless formal invention was designed for feelings like love. Punpun’s bird head explodes with it.

Though Asano’s characters feel entirely, refreshingly real because they are ordinary fools, believers in love, this is not to say that Asano is ever naïve. He paints a bleak picture of Punpun, whose unpleasantness towards girls over the seven volumes grows increasingly pernicious and creepy. But neither is Asano nihilistic.

Punpun’s fall is sad for everyone involved because it grows out of very messed up good intentions. As a child he is essentially pure at heart (as you’d expect a cute, cartoon bird to be), a boy whose defining original sin is as simple and sweet as his failure to live up to a childhood promise to save Aiko from her sad life.

It is only a black-and-white believer like Punpun who could so devote himself to such a bull-headed, stupid, Heathcliff-digging-up-Cathy idea of love.

Like all romantics Punpun takes himself too seriously. How telling it is, for instance, that Punpun believes in a God who hates him. A God, indeed, who shows up to hate him, literally pops up at Punpun’s window with a “Poing” in Book 1 to be an asshole. It is an ingenious conceit.

Punpun’s God is from the wrong end of the spectrum entirely, not a manga character at all but a literal photo of one of Asano’s smirking friends cut and pasted roughly in. He is the image of adulthood and cruelty, of irony and complexity and detail: an image of the Dostoevskyan, self-flagellating conscience Punpun beats himself to death with. It’s a vicious cycle.

Where Punpun’s photographed God is the God of the sad, inevitable adult world, Aiko increasingly becomes something like his God of Love, a manga idol he childishly worships, a light so impossibly bright the more he builds it up the darker the shadow it casts. One God begets the other, and Punpun is torn (eventually, literally) between manga Heaven and an all-too-real Hell.

Just as the kids in Goodnight Punpun’s world all twist inevitably into detail, so Punpun—the sweet manga bird—is literally bent out of shape on his way into a necessarily bitter adulthood. As Aiko inevitably fades from his life and the God of Detail takes greater hold, Punpun’s bird-face undergoes endless metamorphoses into gross, distended, horrorbook shapes.

It is achingly sad. Because it’s not so much that Punpun loses his innocence. Rather it’s the cute bird itself that bends, his very innocence that is so corruptible. It’s a tale for our times. Punpun’s fall is not precipitous but the real world’s slow distortion of once pure feelings.

Read More: Reading Manga: Where to Begin

The great gift of Goodnight Punpun is that to read it is to fall right with him. Aiko, you see, comes back, the desperate dream Punpun has of her comes completely, beautifully, true. And you are lost. Asano drags you off the cliff, nourishing with one hand all the romantic bones in your body while with the other he tears the dream through the seams into a world that cannot contain it.

Goodnight Punpun’s final volumes are the most extraordinary marriage of story and form. Page by page they whiplash you from one end of the drawn spectrum to the other, from a starry-eyed manga fantasy to the ugly God’s point of view, from longing for Aiko and Punpun’s broken love to last for both their sad sakes to the grown up knowledge that it cannot.

Aiko’s desperate desire to have “someone to give up everything and just see me . . . one person who knows me from the top of my head to the tips of my toes without a millimetre of misunderstanding” is the sweetest sentiment when it comes out of her kid self’s mouth, but the only adults broken enough to need each other like this are those too broken to survive it. There’s only one way the perfect drawn dream can bend.

I won’t spoil what happens. Suffice it to say that, though I don’t cry at books, I cry at this one. Those last moments, on the beach, when everything is twisted and grotesque and utterly lovely all at once, affected me like nothing else I have ever read.

Asano draws the dream of Punpun and Aiko so beautifully that you can’t look away, and this is precisely the point. To read it is to have a religious experience, a moment of pure full-body belief in what you know in your head is just a fragile fiction. I was head over heels. It was a kind of falling. There’s a word for this feeling. Perhaps you’ve heard of it?