One thing that is globally known about China, and is undeniably true, is its strict censorship laws and the control which the government has over its media, stretching as far as its social networks.

Censorship in China

I remember being in Shanghai in 2015 when a tragic accident occurred in Tianjin as an explosion took the lives of 173 people. Captured phone footage of the explosion spread like wildfire across WeChat (the popular Chinese social media app), but within twelve hours the video had mysteriously vanished from every phone in the country.

I was shaken to my core at the boundless strength and reach of the arm of Chinese government when I awoke the next morning to find the video absent from my chat logs.

This knowledge had always made me wary of what I read coming out of China. Any Chinese writer who has published works critiquing the ethics of their country’s politics has swiftly fled for their own safety, else been arrested, as is often reported in western newspapers.

And if a writer who has written an honest commentary on modern Chinese politics, economics, and culture has not been arrested, then I regard their words with more than an air of scepticism. Honest? It could not be so.

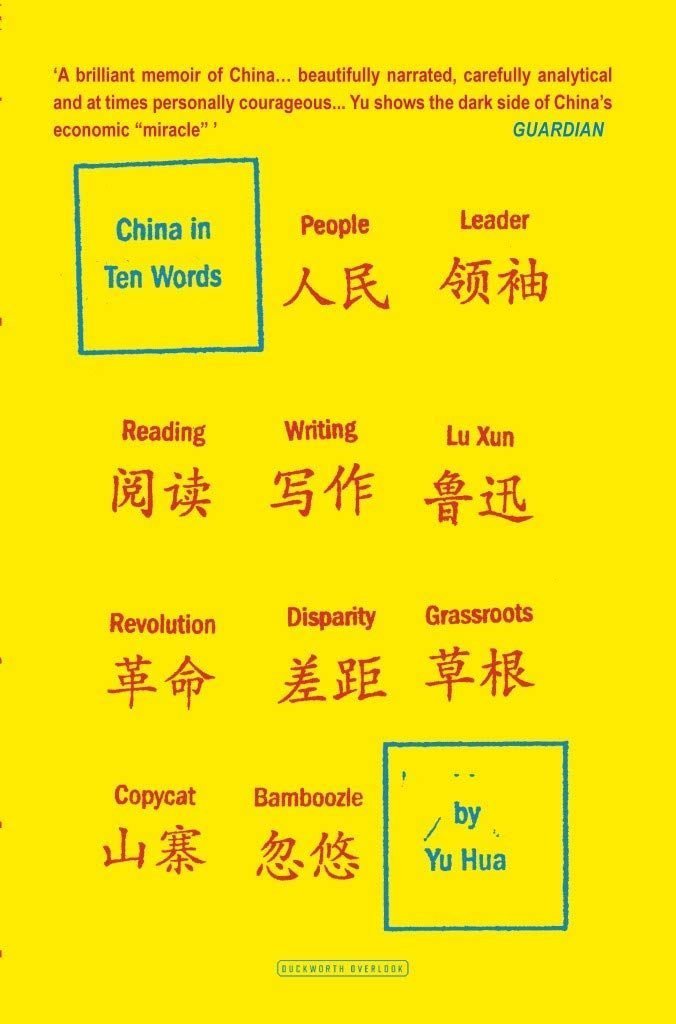

And yet, here is China in Ten Words, a concise examination of modern day China from Yu Hua, one of the Middle Kingdom’s most prestigious writers of contemporary fiction. And to my pleasant surprise, the subjects which comprise this valuable book’s ten chapters are bold, cutting, fascinated, and unashamedly true.

The Weight of Words

At the end of a harrowing true tale that forms the introduction to this book, Yu Hua says that ‘China’s pain is mine’. This phrase has, in one way or another, informed Yu’s decision on which ten words best summarise modern-day China.

Whether it’s due to his own pain or that felt by China as a nation, Yu’s ten chosen words are: People, Leader, Reading, Writing, Lu Xun, Revolution, Disparity, Grassroots, Copycat, and Bamboozle.

In each of these chapters, we find ourselves peering through a window into the lives of Yu Hua himself and the people he grew up with, worked with, or simply happens to have heard of. We also learn about the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward from someone who not only lived through it and survived it, but who also has a masterful gift for storytelling.

We see the true weight of Mao Zedong’s words, the unending limits of his control, the impact of his death, and the shift from communism to capitalism under the rule of Deng Xiaoping. But all the while, this being a window, the feeling that there is thick glass between us and them really never goes away.

This distance provided me with a sense of respect, knowing that China as a culture is truly unique, and perhaps, due to the nature of the Chinese people’s shared philosophies, beliefs, and political agendas, no other nation could have survived what China has survived, let alone thrived at the end of it all.

Revolution after Revolution

During my time living in Shanghai, I was lucky enough to have a job which provided me the opportunity to essentially interview rich and successful local men and women.

So many of them regaled me with rags-to-riches tales, and the almost furious passion which they held for material and monetary gain was almost discomforting, especially given how disparate this passion was from the socialist rules and philosophies which carved out modern-day China only fifty years prior.

And as I approached the end of China in Ten Words, I came to an anecdotal tale from the chapter ‘Grassroots’ which reminded me of the kinds of incredible, at times eccentric, people I was lucky enough to befriend, and left me chuckling:

“A man I know runs a BMW dealership in the city of Yiwu. One day he was visited by an old man from the countryside […] A BMW 760Li with a sticker price of more than 2 million yuan caught his eye. ‘Why is this car so expensive?’ he asked. But when the dealer listed all its advanced features and technological refinements, the old man just shook his head and said he couldn’t understand a word.

Finally, the dealer pointed at the driver’s seat. ‘It took two cows to make this,’ he said […] The old peasant, who as a boy had tended the cattle long before he struck it rich, was won over right away. ‘If two cowhides were used just for one seat, this has to be a top-of-the-line vehicle!’ he marvelled.”

This story is wonderfully and amusingly illustrative of the attitudes of so many older Chinese who grew up in poverty and hardship.

Cows, the deaths of which would have meant the deaths of the man and his family who tended them fifty years ago, could now so readily be chosen, gathered, and slaughtered to make a single car seat in a single car. That was the symbol of privilege and status to this old businessman.

Tales like this one abound throughout this illuminating book. Tales which demonstrate the hardships of the past and the privileges of the present. What is so interesting about this comparison, however, is that it was hailed and celebrated even in the poorest and darkest of times.

The Past as China’s Teacher

Today, Chinese people celebrate the power and money that so many of them enjoy and look back fifty years to the famine as proof. And yet, during the famine and the Cultural Revolution, people were making the same comparisons to their own pasts.

In the chapter ‘Writing’, Yu Hua recalls eating chaff dumplings (made from rice husks and weeds; sharp and painful to swallow) as a child, and the lesson his father taught him with regards to their purpose:

“In the old days, ‘chaff dumplings’ had been eaten only by the very poor, and for us to eat them on the most festive evening of the Chinese calendar was to taste the bitterness of the old society and savour the sweetness of the new.”

The doctrine of Mao’s era was glory and utopia. The people learned to love the time in which they lived, to glamorise it and believe that they lived in a golden age, in spite of their own poverty and lack of personal freedom. Today, the people of China that live and work in the big cities know that this doctrine was not true, and only now can they ‘taste the bitterness of the old society and savour the sweetness of the new’.

Time and again as I read China in Ten Words, I was shocked, even heartbroken, by the hardships which Yu Hua describes having lived through. I was angered by the ways in which so many people were so manipulated by fascism disguised as communism. But I was also made aware of the similarities between the struggles of China and the issues faced by the modern West.

One small story Yu Hua tells reminded me desperately of the control that the media has over so many people in my own country of Britain:

“Once I ran into a reporter who had fabricated […] an interview and I told him firmly, ‘I have never been interview by you, ever.’ He responded just as firmly: ‘That was a copycat interview.’

While the culture of the ‘copycat’ in China is a very unique and fascinating issue, I did not see such a leap between it and the manipulative language and twisting of information used as a means of control by tabloids in the UK and elsewhere.

Conclusion

Lessons abound in this book: lessons about the toil of the average man in Mao-era China; lessons that plead an understanding for the common issues of present-day China; even lessons we can learn about ourselves, our governments, and our laws in the modern West. China in Ten Words is invaluable as a treasure trove of vital lessons about life in China.

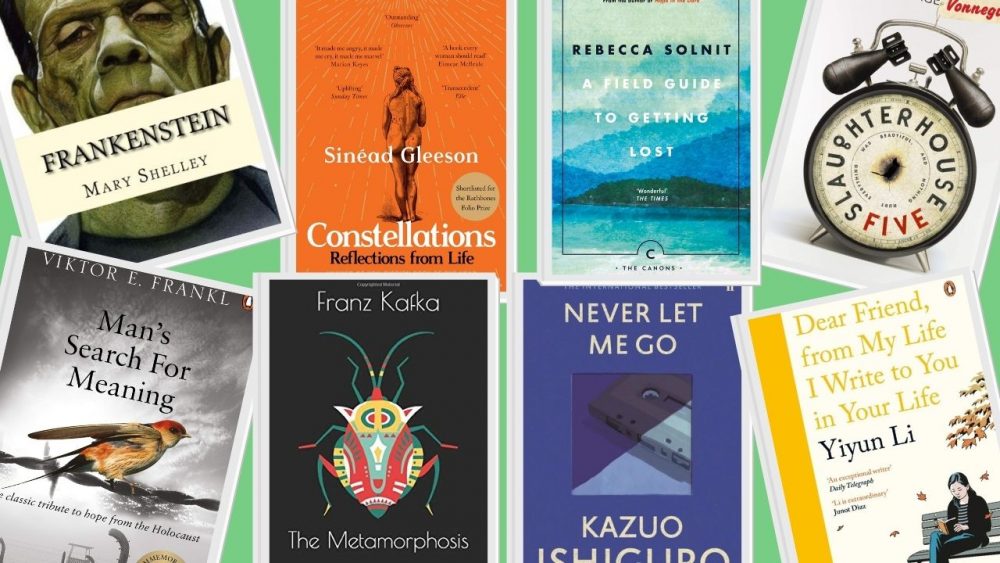

If you like this you might also like: How China got me Interested in North Korea or The New Silk Roads.