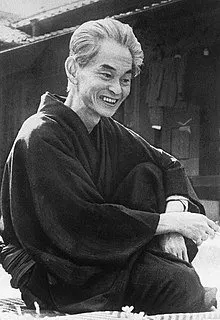

Born into a wealthy Osaka family in 1899, Yasunari Kawabata lived through a tragic childhood, becoming orphaned at the age of four after which he was raised by his grandparents who themselves both passed away by the time he reached his fifteenth year.

Yasunari Kawabata endured the sorrow of his early years and went on to become a highly acclaimed writer in his homeland, gaining recognition right from the very start of his writing career with the publication of a number of short stories, including The Dancing Girl of Izu, not long after graduating from university.

Kawabata would proceed to publish numerous acclaimed novels and novellas, some of which, such as The Master of Go, would initially appear in serialized form in national newspapers. He founded the literary journal Bungei Jidai (The Artistic Age) along with other young Japanese writers, including the modernist novelist Riichi Yokomitsu.

The journal’s philosophy was termed ‘Shinkankukuha’ and sought to explore and deliver new sensations and perceptions in reaction to both the traditionalist approach to Japanese literature and the newly emerging proletarian literature associated with the socialist and communist schools.

In 1968, Kawabata was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, becoming the first Japanese writer to win the award. Yasunari Kawabata died on the 16th of April 1972 and there is still speculation to this day as to whether or not he took his own life.

Related: Japan’s Nobel Prize Winners

Kawabata wrote with a graceful and light touch that retained a sense of refined composure even when dealing with subject matter as dark as suicide, adultery and abandonment. His novels exemplify a honed efficiency, many of them can easily be read in a single long afternoon and even the longer works are written in a clean and concise prose that allows the reader to glide through the pages.

The brevity of many of Kawabata’s writings, however, is not for want of depth or content, but rather evidence of an aversion to excess and an artful balancing of a few carefully selected elements that come across as unmistakably and quintessentially Japanese in character.

Poetry and the Sublime

Many of his novels have the feel of a bell chime, opening with a loaded image that continues to resound throughout the rest of the story before drawing to a close with the final pages of the book.

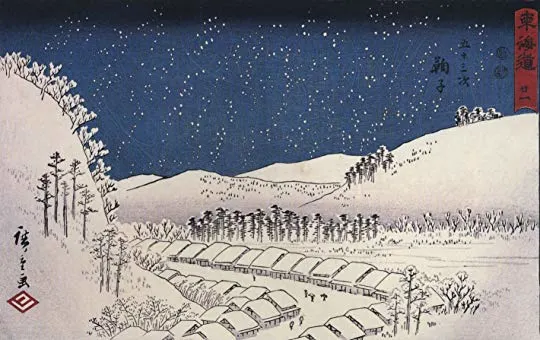

For example, in his most famous work, Snow Country, the novel opens with a train ride through the mountainous countryside in which the narrator, staring out the window, superimposes the reflected face of a beautiful female passenger onto the darkening night sky and landscape outside.

Kawabata’s sparse yet wholly poetic opening is a masterstroke of foreshadowing in a novel that will confront the relationship between art, beauty, lust and love, in a near ethereal landscape, shown through a fragmented and sometimes drunken narration in which the main character finds himself unable to truly feel present and real before the beautiful geisha he has an affair with.

It reaches a harmony in the way the final image of the novel is of a brilliant moon hanging above that same night sky and illuminating the shocking climax.

This same technique is apparent in A Thousand Cranes and The Old Capital which, together with Snow Country, are the works cited by the Nobel Commission in its decision to award Kawabata with the prize.

In A Thousand Cranes the protagonist Kikuji finds himself subject to the manipulations of Chikako, a teacher of tea ceremony and an embittered former mistress of his deceased father, who uses the setting of the tea house to engage in a jealous war against Mrs Ota, another former mistress of Kikuji’s father, who has transferred her affections on to the son.

Early on in the novel we are presented with the image of Chikako sat in the tea house, trimming the hairs from a disfiguring birthmark on her breast as rats scurry in the hollow ceiling and a peach tree blooms outside. A still life that displays both the elegance and grace of the tradition that is the short novel’s setting, whilst simultaneously containing the moral corruption and decay of the jealous flesh that is its story’s principal driver.

A Thousand Words Paint a Beautiful Picture

The Old Capital is set in Kyoto and centres on Chieko Sada, the adopted daughter of a kimono designer, Takichiro, who, whilst mournful at the decline of the traditional arts and crafts, finds himself inspired to produce strange and unusual new kimono designs.

A chance meeting with her estranged twin and a glimpse into the rural mountain life that she otherwise would have lived, set Chieko on a path of doubt and self-questioning.

The novel opens with Chieko stood in the garden contemplating the spring violets blooming on the twisted, moss-covered trunk of an old maple tree. She meditates on two violets in particular that have been there for as long as she can remember yet have always remained a foot apart:

“Do the upper and lower violets ever meet? Do they know each other?” Chieko mused. What could it mean to say that the violets “meet” or “know” one another?…

…Sometimes she was moved by the “life” of the violets on the tree. Other times their “loneliness” touched her heart.

Another perfectly composed still life that gathers together the themes of separation and reunion, youth and age, and the contemplation of beauty that run through The Old Capital.

Beauty and Sadness begins with another train ride and leaves the reader with the lingering image of a rattling chair in a near empty carriage – a fitting metaphor for a story that sees the main character’s long-ago love affair with a young Kyoto artist come back to haunt him and set into motion a calamitous swirl of revenge and eroticism at the hands of the artist’s jealous new lover whose venomous machinations will cause his successful and neatly ordered life to unravel before culminating in a final unavoidable and dreadful act of revenge.

Kawabata’s writing career started and ended with short stories. He developed a style of brief, sharp and lucid prose pieces, often only a page and a half to two pages in length, that he termed ‘Palm-of-the-hand stories’, a delightful image that also serves as the title of a collection of many of these pieces.

Of these stories Kawabata commented:

Many writers, in their youth, write poetry; I, instead of poetry, wrote the palm-of-the-hand stories. Among them are unreasonably fabricated pieces, but there are more than a few good ones that flowed from my pen naturally, of their own accord…. [T]he poetic spirit of my young days lives on in them.

An illuminating commentary as, besides from their brevity, many of these stories operate more like poems in the way that they bind images to moods to convey their insights, often their meanings more in a feeling or an altered perception, rather than in an explicitly articulated moral, much as how the best poetry tends to work.

Highlights include the tragi-comedy of Lavatory Buddhahood, the examination of lust and sexuality in The Shin-O Jizo, and the dark nightmare vision of Goldfish on the Roof.

Tradition vs Modernity

Much of the portrayal of Japan in English-speaking Western world centres on a facade of eccentric kitsch, high-tech neon utopia, and zany video game and anime exuberance; or an equally lampoonable and cliched sense of Eastern mystique.

Anyone who has more than a passing acquaintance with Japan will recognise much of what appears in Kawabata’s work in spite of the time gap.

Kawabata’s characters find themselves anxiously caught between a rigid and stifling expectation of obedience to tradition on the one hand and on the other, a changing modern world that threatens to pull the familiar from under their feet and leave them adrift and lacking solid foundation.

They must navigate the often oppressive world of Japanese custom and social convention, agonising over trying to read the hidden intention in subtle acts; the choice of tea bowl, the patterning of a kimono, the hour to call for a social visit and so on. Here too is the gulf in communication and understanding between the sexes which is further compounded by the divergent world views of the conflicting generations.

Nevertheless, in the spaces between and around the traps and pitfalls of the human social world, shines a calm and often unspoken beauty; Kawabata has a knack for highlighting the tranquillity and sublimity that permeate the pauses in our daily lives.

For those looking to broaden their reading of ‘serious’ literature beyond the Western canon, Yasunari Kawabata is a fine starting point, eminently readable and accessible, providing a glimpse into the troubles of his own time and society whilst still offering us a way of seeing our own.

If you liked this you might like Author Spotlight: The Life and Works of Robert Bolano or Author Spotlight: Banana Yoshimoto.