I’ve written and spoken before about how exciting Chinese literature in the 21st Century is. If you aren’t paying attention to the wealth of imaginative, surreal, political, and evocative Chinese novels in translation right now, you really should be.

Chinese literature, however, has a very particular legacy. So much so, in fact, that this legacy is often simply referred to as the Four Great Chinese Novels. Much like how, when we think of Irish literature, names like James Joyce and Oscar Wilde spring to mind, thoughts of classical Chinese literature, conjure up the names of the Four Great Chinese Novels.

The four great Chinese novels are:

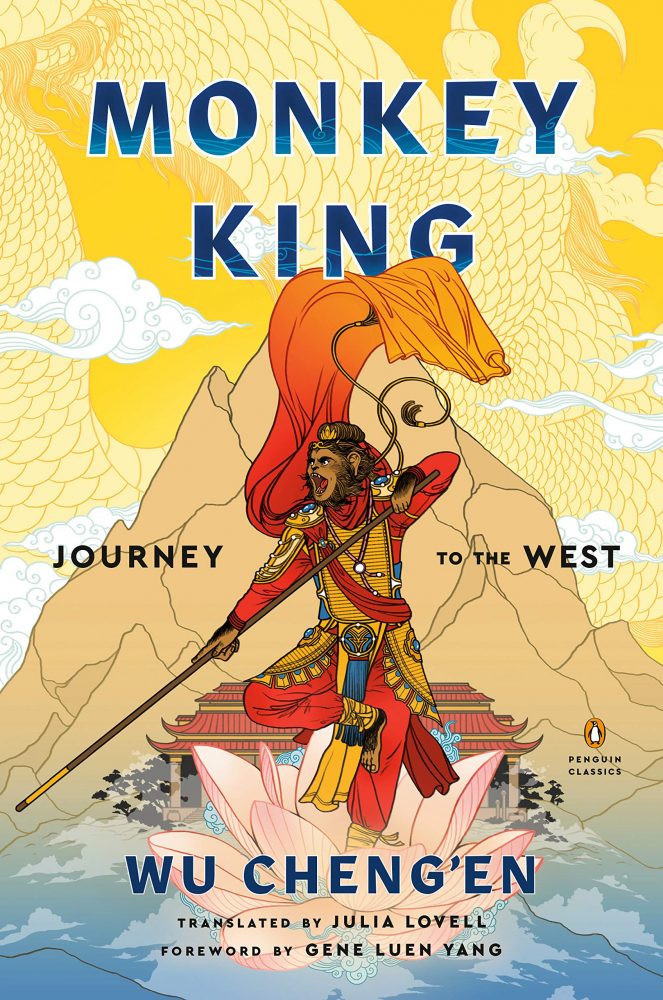

- Monkey King (Journey to the West) by Wu Cheng’en

- Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong

- Water Margin by Shi Nai’an

- Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin

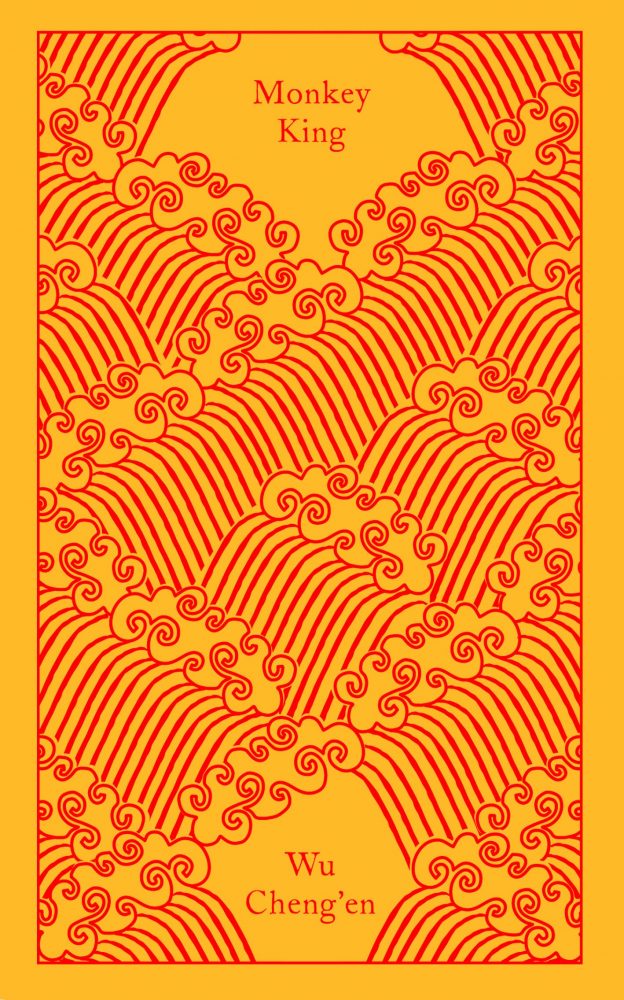

Of the four classic Chinese novels, it is Wu Cheng’en’s Monkey King (Journey to the West) that is most famous. It has been adapted into Chinese films and cartoons, translated into English multiple times (in full and abridged) and was even the main inspiration for Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball manga.

In 2021, we have been gifted a fresh, new translation of Monkey King by scholar and translator Julia Lovell. This new translation of Monkey King breathes fresh life, humour, wit, and charm into the 16th Century classic Chinese novel.

Before we get into what Monkey King is about, it’s worth clarifying the book’s title a bit. In the original Chinese, Wu Cheng’en’s classic novel is titled 西遊記 (Xi You Ji) which literally translated to Journey to the West.

However, most English translations chose to title the book Monkey King or simply Monkey after one of the story’s main protagonists. Around the world, the book is perhaps best known as Journey to the West. However, the new edition which I’m mostly talking about (and the one I have personally read) is Julia Lovell’s Monkey King.

I’ll continue to refer to it by both names but Monkey King is now, perhaps, the definitive English version of the Wu Cheng’en classic.

What is Monkey King about?

The story of Monkey King is split into four parts, though the new translation by Julia Lovell does away with the division of those parts but keeps the chapter-by-chapter structure.

Part One of Monkey King focuses on the titular Monkey. It reads like a Greek or Norse myth as Monkey is born from a rock atop Fruit-Flower Mountain. From here, we follow the exploits of the arrogant, powerful, and stubborn Monkey (whose Buddhist name is Sun Wukong).

During Part One of Monkey King, Sun Wukong trains under a Buddhist master to learn a thousand transformations; he takes a great weapon from the kingdom of a Dragon King; he builds his own kingdom in Water Curtain Cave and rules for centuries.

Eventually, Monkey finds himself in the Jade Emperor’s heaven, picking fights, working jobs poorly, eating other people’s entire feasts, and generally causing chaos. His tearing up of Heaven and Earth ends with the Buddha himself stepping in, defeating Monkey in combat, and trapping him beneath a mountain for five hundred years.

After this setup/prologue, the real story — the Journey to the West — really begins. We follow the origin story of the young Buddhist monk Xuanzang (who was based on a real-life Chinese monk). Xuanzang’s origin story is first established, which includes his father being murdered while his mother is pregnant. From there, she is forced to marry her husband’s murderers.

Once she gives birth to Xuanzang, she sends him down the river with a note and Xuanzang is then raised as a Buddhist monk. Xuanzang takes on several names through the course of the story, including the most commonly-used Guanyin and Tripitaka (named for the scriptures he has been tasked with collecting).

It is this task which takes Guanyin on his journey and makes up the bulk of Monkey King. A Bodhisattva tasks Guanyin with retrieving scriptures and taking them to a kingdom in the south which they have beamed too barbaric and chaotic.

Early in his journey, Guanyin meets Monkey (Sun Wukong), still trapped beneath the mountain. Guanyin frees Monkey and takes him along as a disciple/bodyguard. From here, the Journey to the West really begins.

Julia Lovell’s new translation of Monkey King

In her translator’s notes, Lovell remarks on how her new translation of Monkey King is around a quarter the length of the original Journey to the West. This is a wonderful, practical move on Lovell’s part.

It’s important to say that, if you did not know that this was an abridged version of Monkey King, you never would. This coming from someone who has never read the original Journey to the West. This translation is exactly as long as it needs to be, with the fat cut and the story paced perfectly.

So, yes, this is an abridged version of Monkey King, clocking in at just under 400 pages in length, which is, as I’ve said, perfect for the story it needs to tell.

Lovell also injects Monkey King with so much camp and colour and wit and humour. The book sparkles and crackles with a uniquely British wit. Every line of dialogue drips with sarcasm, snappy one-liners, and laugh-out-loud observations for the lovable bastard that is Monkey.

If you’ve ever wanted to read Journey to the West but have been put off by fears of it being too long, too dense, too dry (as we have all thought when it comes to classics), then put those fears aside. Julia Lovell’s translation is nothing but fun, frantic fantasy writing.

Monkey King brings to mind Joanne Harris’ adaptation of the best Loki stories from Norse mythology: The Gospel of Loki. This was a book that took all the pranks and feats and failures of Loki and stitched them all into one spectacular narrative.

Julia Lovell’s translation of Monkey King comes at this classic Chinese novel with the same attitude that Joanne took to Norse mythology. She has injected the book with energy, spice, and humour. The dialogue is spicy and quick; the events are larger-than-life; the pacing tight and frantic.

While I admit to having no other translation to compare it to, I can’t imagine having more fun than I did with Julia Lovell’s hilarious translation of this Wu Cheng’en classic.

Why Monkey King is One of the Four Great Chinese Novels

If you look at Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey or the Norse Eddas and Sagas, you’ll find ridiculous tales of gods and monsters. You’ll find heroes and champions accomplishing impossible feats. You’ll find tricksters causing chaos through magic and godly powers.

The stories of mythology always involve magical monsters and godly things defying the rules of nature. They transform and disguise themselves; they live for thousands of years; they mould and shape the world to their liking. And they often do it all in the name of fun or simply because they’re bored, horny, or both.

Monkey King is one such story. It might be a classic Chinese novel (one of the four great Chinese classics), but it still reads and behaves like a collection of myths. It is a book populated by ethereal creatures, trolls and goblins and monsters. The literal Buddha traps the titular Monkey King under a mountain just to shut him up, for god’s sake.

There is so much colour and strangeness to Monkey King. One entire chapter is dedicated to a Dragon King who tries to trick a fortune teller, leading him to defy the decree of the emperor Taizong. When Taizong himself dies prematurely, he appears at the Court of the Underworld after having been sued by the Dragon King.

This is only one of dozens of bonkers stories that serve to flesh-out the stories of Chinese mythology that are found between the pages of Monkey King. Put simply, there is no end to the fun and joy gleaned from a reading of Monkey King by Wu Cheng’en, newly translated with wit and humour by the incredible Julia Lovell.