So, you want to learn more about the history, politics, and culture of China and you’re looking to read some books about China in order to do that. Do you pick up a novel by a Chinese author or search for a Chinese memoir?

I suspect most English-language readers would go for fiction. It’s so much more easily available, for starters.

In the Paper Republic roll call of books translated from Chinese in 2020, only a tiny number were contemporary non-fiction. That is a pity. Novels are works of the imagination, by their very nature.

Must-Read Nonfiction Books About China

For facts and real-life stories, I am a big fan of literary non-fiction. Chinese essays and reportage, memoirs and blogs are often very good reads: incisive and witty, and every bit as entertaining as a novel.

Plus you can be sure that they will represent the writer’s unvarnished views of their country and give a fascinating glimpse into their thoughts.

Let’s talk about some essential nonfiction books about China to illustrate my point.

China in Ten Words, essays by Yu Hua

I have read many books about China, as well as online posts and blogs by Chinese writers about China, but few have had me riveted the way this one did.

Not surprisingly, considering its acerbic tone, it has never been published in mainland China, although an edition came out in Taiwan in 2011 (《十個詞彙裡的中國》) and it can be found online in simplified Chinese.

There are quotable quotes on every page. It is almost impossible to choose from them. There are jokes, perceptive analysis, personal stories and historical context, all in one medium-sized volume.

One of the remarkable things about Ten Words — undoubtedly one of the best books about China by a Chinese author — is that it has something to say not only to those who want to know about China (but don’t know much yet) but also to readers who already know a fair bit.

As one of those readers, I was shocked at Yu Hua’s story of a three-year-old being denounced during the Cultural Revolution for saying ‘the sun has gone down’ (the sun being Chairman Mao’s emblem).

I recognised from my own experience, his observation that most of today’s younger generation know nothing about Tian’anmen. And I was charmed by his description of his thirst for reading material as a child: ‘I would pick up the Selected Works [of Chairman Mao] and read it avidly by the light of the setting sun.

The neighbors all sighed in wonder, impressed that at such a tender age I was already so assiduous in my study of Mao Zedong Thought. My parents brimmed with pride on hearing so much praise. …In reality Mao Zedong Thought had completely failed to engage me.

What I liked to read in Selected Works was simply the footnotes, explanatory summaries of historical events and biographical details about historical figures, which proved to be much more interesting than the novels in our local library.

Although there was no emotion to be found in the footnotes, they did have stories, and they did have characters.’

Yu Hua’s essays — which comprise one of the best books about China you could ever hope to read — also bring us bang up-to-date and into today’s get-rich China. There are various mirth-making scams recounted in the Bamboozle chapter, perpetrated on the government by its people.

One city decided to set its teachers an examination in a bid to raise teaching standards. But it acknowledged that single-parent teachers had a hard life and exempted them. There was a sudden outbreak of divorce … and re-marriage when the exam crisis was over.

Something similar happened when some farm land was redistributed. ‘Just how much square footage each … peasant should get involves a complex computation that takes into account the size of their original house and the number of their family members, but marital status is the most crucial element.

Marriage and divorce, remarriage and redivorce, thus become the instruments of deception and subterfuge.’ That made me smile… I have known people in London do the same.

See also: Will Heath’s review of China in Ten Words

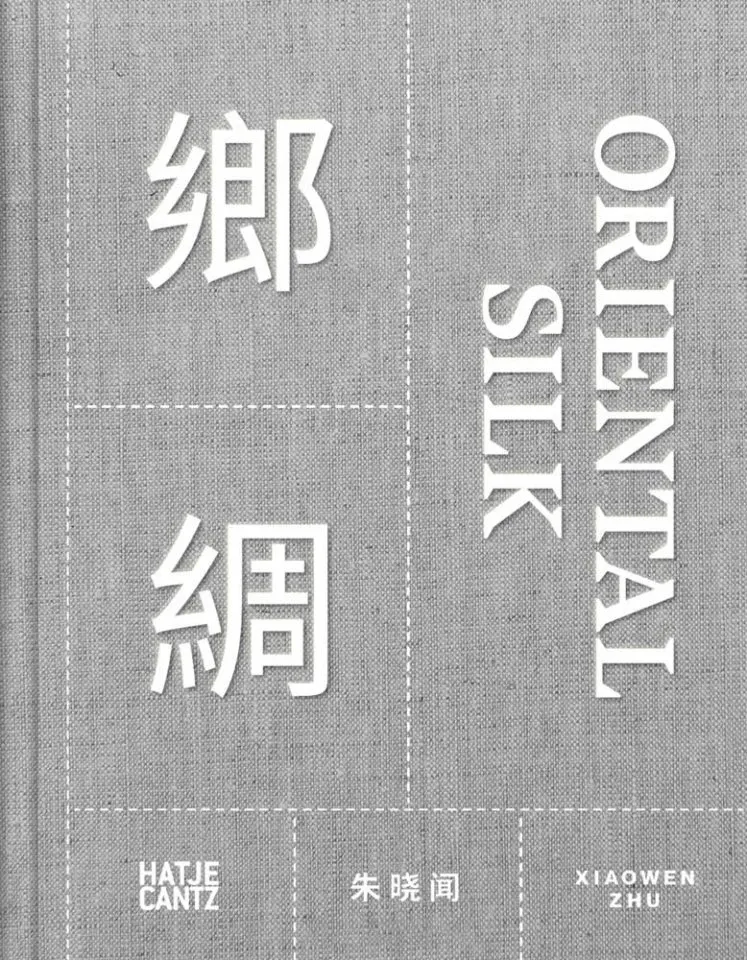

Oriental Silk by Zhu Xiaowen

My second choice for this list of essential nonfiction books about China is Oriental Silk, by Zhu Xiaowen. It tells the story of a Chinese family who emigrated to America and opened a shop importing that icon of Chinese culture – silk.

It is a truism, for most of us, that the Chinese and their shops are everywhere in the world. But how many customers know the back-story of the families who run them?

This book is Zhu’s account of her chance encounter with Kenneth Wong and his store, the eponymous Oriental Silk, and the stories he told her.

Wong’s great-grandfather went to America, then Mexico, where he made his money in casinos, before going back to China and losing every cent.

Ken’s father who left Guangdong again for Los Angeles in the late 1930s and settled there, serving with distinction in the US armed forces during the Second World War and helping to liberate Auschwitz. In the meantime, his wife and daughter lived through the almost unbelievable horrors of the Japanese occupation of China.

Once the family were united in Los Angeles after 1945, Ken’s parents set up a couple of small businesses, culminating in the Oriental Silk store in the early 1970s.

The store became famous, the go-to place for Hollywood film-makers in search of fabulous high-quality fabrics for their film costumes.

In a reversal of the usual order of book-to-film, Oriental Silk was only written up as a book after Zhu had made her film about the Wongs.

It is a beautiful hardback, with a pale grey tactile cover and intricately designed pages, an artist’s book, but it is Wong’s family history and his memories that take pride of place.

Zhu Xiaowen herself has said, ‘Behind every person is a story.’ This book is about one family’s inner, and outward, journey.

Excerpts from the film that Zhu Xiaowen made can be seen here, and give a better idea of the beauty of the fabrics and embroidery.

Read More: Must-Read Chinese Science Fiction Books

More than One Child by Shen Yang

My third choice for essential books about China is a memoir. Shen Yang was born a second daughter, during one of China’s biggest-ever experiments in social engineering — the One-Child per Family Policy.

She had to be hidden from the authorities from birth, and grew up, unwanted and illegal, in the family of an uncle and aunt who were volatile and sometimes abusive towards her.

All of that said, More than One Child is by no means miserable. Shen Yang is often funny and always sharply observant, and this is a colourful and, ultimately, uplifting read.

Instead, let me say something about the challenges of translating what I can only call ‘new-speak’.

One-Child per Family, a new policy, gave rise to a whole new language, both in the form of slogans and of words to describe the children, whether they were first-born and legal, or subsequent children and thus illegal.

In Shen Yang’s Foreword, she writes, ‘At the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, when family planning was strictly enforced, and social controls were tightest, the ubiquitous wall slogans were intimidating and even contained direct threats.’

Translating slogans is a bit like translating song lyrics. They have to go with a swing. Puns, alliteration, rhymes… Chinese slogans have them all. Here is a sample of some where, horrible though they are, I had some fun creating a translation:

‘Give the snip to poverty, coil yourself in money.’

Original: 结贫穷的扎,上致富的环

Here, I used ‘snip’ to keep the reference to tubal ligation/vasectomy, and ‘coil… in money’ to pun on the birth control coil.

Another: ‘If you won’t have your tubes tied, we’ll come down on you like a ton of bricks; if you won’t have an abortion, we’ll pull a ton of bricks down on you.

Original: 该扎不扎,巨额严惩,该流不流,拆墙扒房。

It helped that in English, to come down on someone like a ton of bricks means to criticize or punish severely; and the second part refers to the practice of punishing multi-birth families by pulling their houses down.

So, no, the word play in the English does not reflect the Chinese, it is original. But the translation accurately conveys the meaning.

Then there are the words used to describe the first-born and subsequent children. Chinese is very concise and that conciseness had to be reflected in the translation. 独生子女… just four characters, for the legitimate, licensed first-born, the ‘only-birth-son-daughter’. I called them ‘only-children’, hyphenated.

Finding an English word for the illegal ones, the ‘second or third birth, (and some women even had five or six)’ as Shen Yang writes, was a different problem. In Chinese, they were variously called 超生儿, literally, excess-birth-children, or 小黑孩。

This term presented us — translator, author and publisher — with a problem, because it means ‘black child’. Not, of course, a reference to skin colour, but to the fact that she or he had been born illegally.

We tossed around a number of possibilities before settling on using the pinyin, heihaizi, in combination with the term ‘illegals’. ‘New-speak’ language often demands creative, new-speak translation.