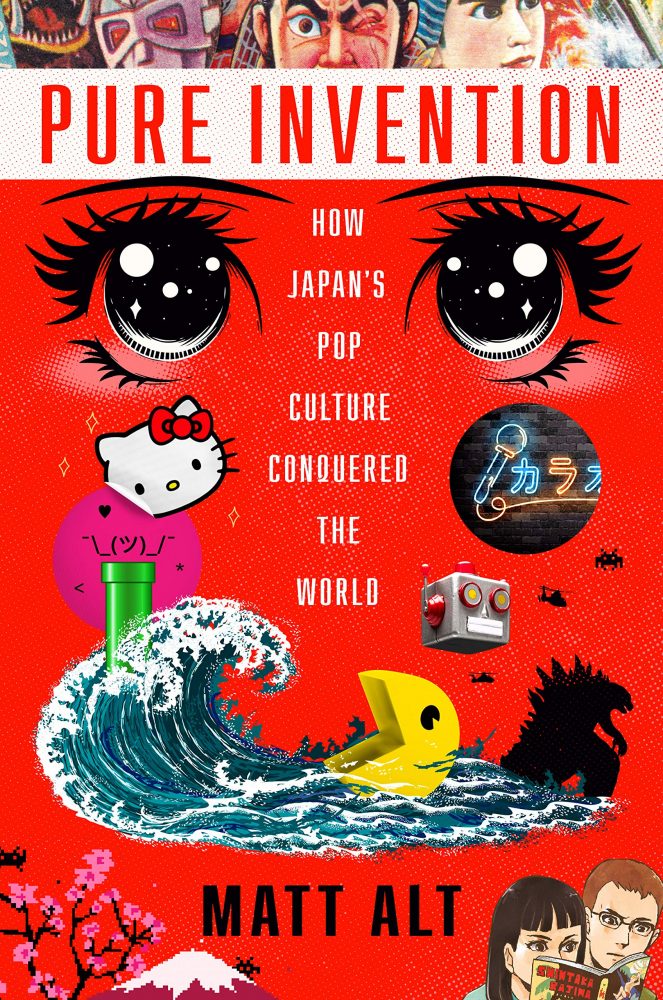

The full title of Matt Alt’s book is Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World. And this ambitious title is right on the money in ways that will surprise and delight you, no matter how prepared you feel going in, or how much you already think you know about Pokemon, Gundam, or Hello Kitty.

Pure Invention is a deep, deep book. It is one that pulls us down a rabbit hole into a vast labyrinth of Japanese history, tradition, innovation, art, design, technology, and the people behind all of this. It is a book in two halves: the post-war, pre-bubble-burst Japan that led the world in the realm of design and invention; and the post-bubble Japan that, well, kind of did the same again.

Both of these periods were shepherded along by the savviest designers and cultural innovators of their time, and both were pulling the nation out of a murky kind of failure at the brink of national poverty and international irrelevance.

The entire book takes us on a chronological journey through 20th century Japan and into the 21st century. Along the way, it introduces us to the people who invented revolutionary new tech and led the charge in fashion and cultural trends. Some of them you’ll know, and many you won’t.

Toymakers, pop idols, animators, writers, artists, businessmen, engineers, designers. The geniuses who not only saved Japan’s economic and cultural future after World War II but transformed the country into the one that all eyes fell on during the 70s, 80s, 90s, and beyond.

In the savviest of ways, Alt doesn’t just present Pure Invention as a chronological history book, but also finds a way to divide its chapters up by themes and cultural talking points. There will be a chapter on Hello Kitty, another on anime or video games or karaoke.

Each of these chapters begins a few years forward in time and paints a picture of what has been achieved – through an anecdote or the close-up of a moment in time – before slingshotting us back to the beginning of that cultural icon’s journey and how it got to that point.

The fact that these chapters are so clearly divided while also being more-or-less chronological shows how these cultural icons bled into one another and evolved over decades. From one angle (and this book has many), Pure Invention can be read as the bible of your childhood. For countless Americans and Europeans, Japanese exports represented the scaffolding of our childhoods.

We were hypnotised by the Pokemon and Tamagotchi crazes; we learned our moral lessons from anime like Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Moon. We locked ourselves away to play Nintendo and PlayStation games, rather than play sports outside. What Matt Alt’s book offers us is both historical and cultural contexts for the hobbies we all grew up with.

Read More: Books to Read Before Visiting Japan

For many, myself included, these hobbies have remained with us deep into adulthood. I’m a thirty-year-old man who spends half his time in Japan and gets paid to write about video games and anime.

These passions have never left me. And yet, even given my own dedication to Japanese history, pop culture, language, food, etc, there was still so much to learn in Pure Invention that I not only had no clue about, but had never even stopped to consider.

Alt offers us answers to questions we never asked, but are so happy to now understand so clearly and intimately. He offers us both a history of our favourite media and hobbies, and a cultural, financial, and political context for why these things came into being in the first place.

This context extends from the evolution of kawaii culture and the Japanese schoolgirl as a cultural force to the reasons behind the existence of hikikomori and otaku.

Matt Alt considers the infamous bursting of the economic bubble at the end of the ‘80s and how it would mean a different world for the post-bubble generation of Japanese than the one their parents had enjoyed, and he offers this sudden economic shift as one explanation for otaku culture: women finding solace in the kawaii things of their girlhood, and men obsessing over anime and video games in the same way they had when they were in elementary school.

To read Pure Invention is to enjoy a wonderful melding of nostalgia for the things we grew up with and an education in Japanese post-war history, economics, politics, and popular culture.

It’s an ambitious book, to be sure, and what makes it even more ambitious is its impressive breadth of biographical content. From “Kosuge the Car Man”, a toymaker who single-handedly pulled Japan’s economy from its post-war wreckage, to animation mastermind Hayao Miyazaki, who is today a household name around the world; the sheer number of Japanese artists, designers, businessmen, and innovators we get to know with such splendid dimensionality here is, frankly, unbelievable.

It’s a dizzying amount of information that must have taken countless hours of research. And I, for one, am incredibly grateful.

Reading about Kosuge alone, and considering how his designing of a toy version of American Jeeps for children was the thing that not only saved Japan’s post-war economy but also changed how the world saw Japan after the war (from international laughing stock to a nation of revolutionary engineers and innovators), it’s impossible not to get chills when pondering the ripples that bled out from the actions of one toymaker.

Read More: Japanese Literature in 12 Genres

To get such a vivid, clear, and colourful look at the landscape and history of Japanese pop culture, populated by these incredible women and men – choreographers of not only Japan’s 20th century cultural zeitgeist, but the Western world’s as well – is truly astounding.

Beyond the heavy stuff – the biographies, the economics, the philosophical discussion about kawaii and otaku culture – are the facts. Every chapter of Pure Invention is littered with fascinating facts about Japanese language, tradition, and aesthetics.

Like how “emoji” has no relation to English but is, in fact, a portmanteau of “e”, meaning picture, and “moji”, meaning character. Or how the word “otaku” comes from a formal and distancing honorific for “you” which was typically used by old ladies, and which teenagers jovially inserted into their vocabulary.

Or how Sony’s executives only gave the original PlayStation the greenlight because “they believed as many or more customers would purchase the console as singing machines as they did for gaming.” Or how Donkey Kong’s name came around because Miyamoto was looking for the international symbol for stubbornness: the donkey.

Or how Mario falls into the concept of kawaii perfectly, by virtue of being a fairly pacifistic protagonist with an adorable gorilla as a villain. The only downside readers may find when reading Pure Invention is that, if they have picked up this book because of a passion for Japanese pop culture, they may care far more about some chapters than others.

I can’t deny having far less interest in karaoke machines and Walkmans than in anime and kawaii culture. But to pass over these chapters would be a tragic error. Every single chapter has so much to teach us about a different aspect of Japanese culture, in a context far broader than popular media.

The chapter on karaoke, which I had little excitement for at first, taught me so much about the daily lives of not only Japanese salarymen, but also their wives during the economic boom that was the 70s and 80s. The turn of every single page is the introduction to a new, fascinating, and valuable piece of the puzzle which, in the end, forms an almost complete 3D image of Japan in the second half of the 20th century.

Conclusion

As a child of the 90s who grew up on Nintendo and shonen anime, there was so much rich and exciting material here for me to feast on; so much to learn about the things that I had always loved so dearly, the things that have slowly become my livelihood.

But far, far beyond just that, Pure Invention provides us a vibrant, detailed, and lavishly painted portrait of Japanese history and culture beyond World War II.

It reframes Japan’s economic and cultural achievements. It shows us, definitively, that Japan’s pop culture really did conquer the world.

That the world as we know it would be unrecognisable were it not for seemingly small things like Hello Kitty and Akira. Few books on Japan offer as much depth and value as Pure Invention.