Forgotten Reflections is a tale of survival and the ability to flourish through adversity during a devastating period of modern Korean history: The Korean War. I had the opportunity to get in touch with Young-Im Lee and ask her a few questions about her novel, her own life, and her feelings about modern day Korea. Her answers were as thought-provoking and insightful as her fiction.

Young-Im Lee has painted a truly staggering and diverse world that seems entirely removed from the modern day, and yet is immediately recognisable.

Q: As a Korean national who spent her youth away from home, you have a unique perspective on your own country. Moving to Seoul, what were your initial impressions with regards to social issues, politics, and education?

When I first moved to Seoul, I was eighteen, young enough to be enthralled by my prospects of studying in Seoul, but also only viscerally aware of the social issues that made the news. Growing up in the Philippines, our family would often host kids who visited from Korea to study English for a few months.

These students tended to be the ones who were having a difficult time adjusting to the rigorous Korean education system and were considering relocating abroad. Because of this, I think had quite a negative impression of the Korean education system from a young age and was quite nervous to relocate to Korea.

Nevertheless, I jumped into teaching when I began my studies in Seoul to earn what I could, only to realize that my fears of the Korean education system seemed to be mostly true.

Rote memorization was the norm and kids were not encouraged to ask questions. Worse yet, I saw children scolded for asking the same questions that I remember being praised for as a child, and the same seemed to occur at home where the parents’ authority was not to be questioned, so reasons were never given for why certain things were the way they were.

I believe a large part of my identity formed around being “different” from these kids, but as I grew older and the kids I taught grew younger, I began seeing the larger social issues that stem from these issues. In an academic setting, I would call this critical thinking (or a lack of imagination), but in a larger social setting,

I could see how Korea’s development as a first world country would surely be stunted if the next generation isn’t trained to be leaders, critical thinkers, and imaginative forward-thinkers.

This novel, in essence, is my way of showing how various social, historical and cultural issues have led to the modern generation and is also a cautionary tale that urges us to break the trends of our past to move beyond our traumatic history.

Q: Reading your novel, it only throws into sharp relief how incredibly far Korea has advanced since the Korean war, especially in terms of politics and economics.

We all have ideas on how we would like our own nations to progress; what aspects of Korean life would you like to see develop further (such as in the areas of laws, international relations, feminism, or education)?

I can’t say much about the economy and politics, but lately, I have become more acutely aware of issues that stem from our patriarchal social structure.

If my early twenties were marked by struggles of national and ethnic identity, my mid-twenties have been marked by a growing awareness of gender inequality in Korea.

My first real wake-up call occurred sometime during university. My calculus 101 professor had been extremely generous with his time and had often invited us to expensive lunches. I even went to him for support when my grades were suffering and I didn’t think twice about his generosity other than how impressed I was that an internationally-acclaimed mathematician would be so giving to his students.

A few years later, I received news of a math professor—the very same one from my university who was being prosecuted for sexual misconduct! I was confused, grateful nothing had happened to me but mostly shocked. Before then, it never occurred to me that someone in that position would take advantage of the naiveté of those under his supervision.

Although I do not claim that this case is solely the product of a patriarchal culture, it opened my eyes to various safety concerns and inequality that could stem from not only the physical differences in strength but also the social conditions that keep women silent.

Just a few months ago, I had witnessed first-hand, a couple bickering in the streets outside of my apartment. The conversation became violent and the police were called on to stop the fight. I had walked up to the police officer to make certain he knew the man had beaten her, but the police officer told me (in no uncertain terms) that such cases of domestic violence are never prosecuted and how the woman will not be pressing charges so I shouldn’t bother speaking up.

I can only imagine how much courage it takes for a woman in this situation to run from abuse. But to think the social systems in place are more likely to discourage action from women who are already in quite a vulnerable state made me angry.

There is certainly a long way to go. I believe issues of gender inequality are entrenched in a system, history, and culture that touches every part of our daily lives. I hope to bring more awareness to this issue as I gain a deeper understanding of it.

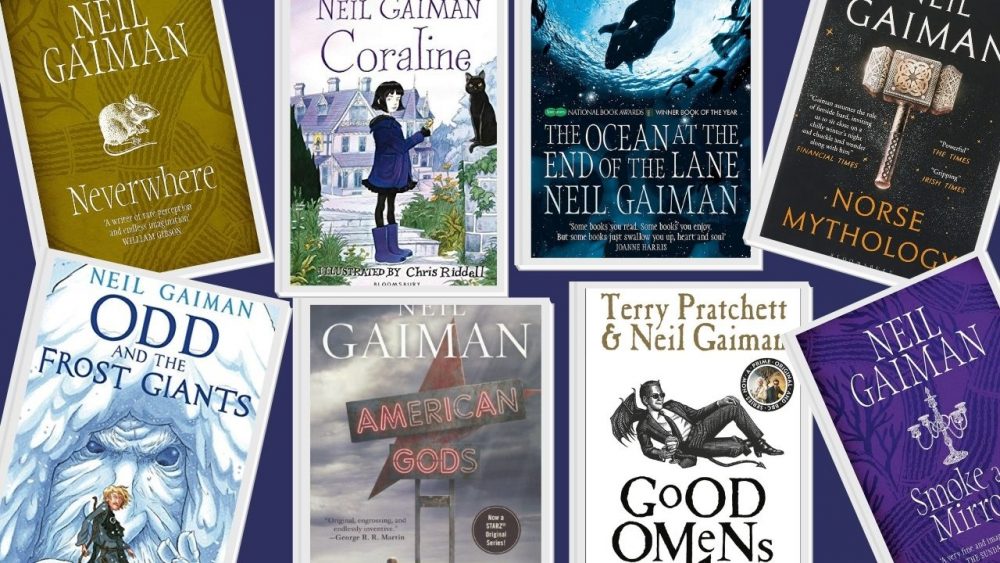

Q: You’ve cited Murakami as an influence on your writing. Are there any other East Asian authors that have also inspired you as a writer or simply as a reader?

Perhaps because of my international upbringing, I have always felt somewhat limited by categories like “Korean Fiction.” (Although I must admit, I still categorize my book under the “Asian Historical fiction” subsection on Amazon).

Of course, I admire many East Asian authors for their ability to represent their respective cultures to an English-speaking audience; however, most of all, I appreciate the way in which authors strive to represent universal issues and values that go far beyond their respective geopolitical borders.

For instance, I admire Kazuo Ishiguro’s chameleon voice that convincingly depicts various ages, genders, and ethnicities.

As I develop my next writing project, I am becoming more aware of the expectations a reader might have of a Korean writer. In fact, while I am very happy that so many people enjoyed this story, I am also aware that many of the people who have read and commented on my work were from the U.S. or Europe.

While it was always my intention to write for an international audience to encourage those who are coming of age, and to help bring some foreign aspects of Korean culture into context, I had also intended for this book to be read by Koreans or others nation groups who have had a similar historical trajectory of imperialism or colonization to encourage people who have gone through such a turbulent past to understand why we may be having a crisis of identity.

Despite the struggles of reaching an international audience (a struggle that I believe is also universal for many writers), I hope to continue to write with universal issues and values in mind.

Young-Im Lee has also provided us with a short essay chronicling her own thoughts on the novel, what it speaks of, and where the initial idea came from:

I would like to think there are many threads to the story.

On the surface level, this book was my attempt to not only shed light on the heroism of women during the war, but also highlight the deep suffering, they experienced and how these unseen joys and sorrows made a mark in the silent records of Korean history—a history that is quick to mark the deeds of men who, more obviously sacrificed their lives as soldiers.

Yet, on a more fundamental level, this is the story of men and women who must find a way to bury their childhood dreams as they face the harsh realities of adulthood ahead.

This, I believe, is a universal experience that transcends time and place and affects all generations equally.

We all grow up, but what happens when our hopes and dreams are met with reality? How do we come of age?

And how do we revive our dreams later on in life and in future generations to fulfil the dreams we were never given the chance to pursue?

In many ways, this book was quite a self-indulgent project that helped me work through my identity crisis. I left Korea when I was one and have lived outside of my passport country for over 20 years. I had always been a “foreigner” and I was comfortable with that.

Like many third culture kids who return to their so-called “home countries,” I was bombarded with assumptions and generalizations from people who probably thought I was strange, developmentally challenged, or just one of those Korean-Americans.

Perhaps, it would have been easier if I could just identify as Korean American. But the reality is, I am Korean by ethnicity and by passport. Simple and clear cut. Or so everyone seemed to assume.

It then struck me! These entangled struggles of growing up and dealing with an uncertain identity seemed to logically converge during the Korean War, an era that could encapsulate not only dashed childhood dreams but also the same thread of identity crisis I have been experiencing.

During this turbulent, confusing, but also hopeful period, I could imagine young adults lived with confused identities in the midst of political agenda (During the Japanese occupation, Korean children were given Japanese names and were not allowed to speak Korean).

What happens when children, who are never given the opportunity to discover who they are, are suddenly given hope for a better future (in the form of Korea’s independence from Japan and the subsequent creation of the Korean governments), only for these hopes to be dashed by war less than two years later?

A simple line repeats itself throughout the novel: “We were born before our time.”

Each generation represented in the novel reiterates this phrase, whether it is from Jung-Soo’s father who declares he is born before his time because no one could understand the grand visions he had of a full-fledged, developed and thriving Korea, or Jung-Soo who spends the entire novel struggling with his identity, only to discover it at the very end, but never get the chance to live out his visions.