When I was living in Inagi-shi, a once-upon-a-time small city now swallowed up by the swell of suburban Tokyo, I would enter the convenience store next to my apartment every morning and buy a sugar-soaked bun to walk to the station with. The convenience store woman who served me each and every morning at 8 am was a middle-aged lady, sweet as the buns she sold me.

She would greet me time and again with the same rising and falling pitch of her voice as she almost sang, ‘ohayou gozaimasu!’ The phrase beginning low, reaching a squeaky midpoint and at last dropping to a near growl at the end. She said it all with a toothy smile that some might call robotic or automated, but I was lulled to joy by each and every morning, rain or shine.

That wonderful convenience store woman helped me get my best foot forward as I started my commute into the centre of Tokyo, and I’ll always be grateful to her for it.

As I devoured page after page of Convenience Store Woman I imagined its setting to be that same convenience store in Inagi-shi, and its wonderfully odd protagonist, Keiko, to be my same convenience store woman with her clock wound back a decade or so.

Read More: Review of Earthlings by Sayaka Murata

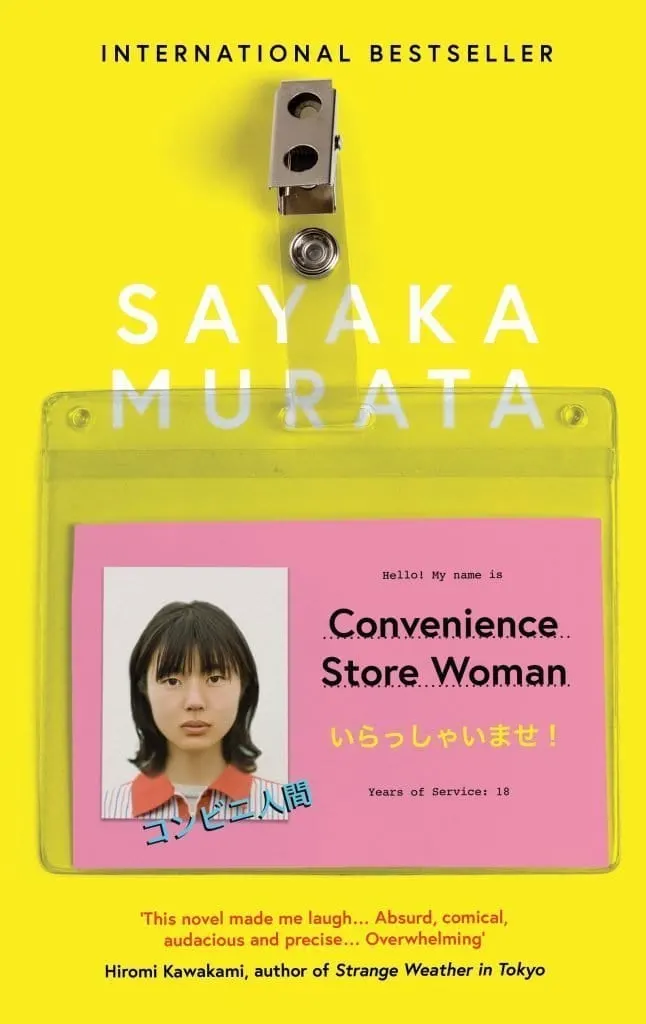

Convenience Store Woman

“It is the start of another day, the time when the world wakes up and the cogs of society begin to move. I am one of those cogs, going round and round. I have become a functioning part of the world, rotating in the time of day called morning.”

Keiko Furukura is thirty-six and has worked part-time in the same convenience store for eighteen years (as, in fact, has her creator). She has seen eight managers – whom she refers to only by their numbers – and more co-workers than she could count.

She is entirely content with her life, and has never asked for anything more; not a better job, more money, nor even a partner to share her life with.

She is a cog in the convenience store machine, as much a part of the furniture as the fluorescent bulbs and door jingles (even the Japanese title, ‘Konbini Ningen’ or ‘Convenience Store Human’, reflects this with clarity: Keiko is not a woman, she is a human part of the store machine). As a result, this cog has never managed to fit the greater machine we call ‘modern life’.

Japan, as much as any other nation in the developed world, operates by a set of rules commonly referred to as: marriage, university, promotion, pregnancy, and mortgage (possibly not in that order).

Many young people today forego much of this, either through personal choice or due to economic restraints. Japan has seen a consistent fall in childbirth rates over the past twenty years, and many twenty-somethings are abstaining from sex and opting for an asexual lifestyle.

Keiko fits that mould (though not through choice nor financial issues, but rather for her own safety; something we’ll touch on in a moment) but her friends and family will not stand for it. To quote the mother of British comedian Greg Davies, ‘It’s not normal, love!’

“The normal world has no room for exceptions and always quietly eliminates foreign objects. Anyone who is lacking is disposed of […] Finally I understood why my family had tried so hard to fix me.”

Taking a Stand Against Almost Everything

Just now we mentioned Keiko partaking in a lonely, repetitive, celibate lifestyle for her own safety. This is brought to light early on as a flashback to her childhood reveals that Keiko has the inability to read facial and voice cues, and other such quirks which lead her into some borderline dangerous situations and which heavily imply that she has undiagnosed Asperger’s syndrome.

Rather than provide any emotional, psychological, or medical support, her family merely treat her as an oddity and as a result Keiko is left to prescribe herself a life of safety, seclusion, and simplicity.

At first, I was frustrated with Murata’s choice to add Asperger’s to Keiko’s list of things that make her ‘different’, feeling that she was being stretched too thin as a character. This was until I came to understand the writer’s intention: to bring to light unspoken issues with mental and emotional health in Japanese society.

Keiko remaining undiagnosed and shunned by her family – all of whom literally cry out for her to just be normal – deep her thirties is a painful and heart-breaking plea by Murata for her home country to raise its awareness and have a greater discussion regarding mental health and the emotional needs of its people.

“[Keiko’s sister is] far happier thinking her sister is normal, even if she has a lot of problems, than she is having an abnormal sister for whom everything is fine. For her, normality – however messy – is far more comprehensible.”

Keiko’s sister finds it unacceptable that her ane be safely interred into a life in which she feels safe; she must instead partake in the parts of life which render her frightened and confused, merely for the sake of better fitting the mould. By this token, Murata is not only taking a stand against Japan’s ignorance of mental health, but also its rigid following of the rules laid out by decades of repeated systematic normality (or ‘tradition’ as most people refer to it).

An Existential Crisis on Paper

There’s a trend amongst my fellow millennials, myself included, to fall into a pit of anxiety that only deepens with each passing year. Gone are our fathers’ midlife crises and in their place are the perpetual crises born from our fear of growing old or of failure (whatever that might mean to us as individuals). This is terrifying; it is also popular discourse these days.

For Keiko, however, this is not something she fears. Rather, it is a motivator for those in her life who are chastising her; they are afraid on her behalf, afraid that she will not accomplish enough in her life. This is a worry that Keiko does not understand. For her, a life without this anxiety, a life filled instead with comfort and simple pleasures and things that she understands is far more enjoyable.

Conclusion

Depending on your own disposition, Convenience Store Woman may serve to further kindle the flames of your own existential nightmare, or it may satiate your fears just a little.

Keiko is pressured by those around her to make something of herself, and the person who understands her best is a raucous and barbaric moron who, as written by Murata with hilarious accomplishment, serves as the typically hyper-aggressive masculine counterpart to her far more relaxed take on irregularity in the face of ordinary society.

This pressure breaks her a little, but it also doesn’t. And the ride she is taken on may lead the reader to feel like all of this-this life of ours – is useless and so the crisis sets in anew; or it may liberate them from that lurking, looming fear of failure and stagnation. In that sense, we really feel like we have to work with Keiko, and I am happy to do so. She is a truly wonderful character.

I also personally refuse to believe that Keiko for a moment should bow down to the whim of regularity. If she has to, then so does my own convenience store woman from the 7-Eleven in Inagi-shi, and I refuse to let her kowtow to anyone or anything; she’s far too special for that. I highly recommend that you purchase this wonderful novel. In fact, I cannot recommend it enough.

If you’re interested in this book, you’ll also love The Last Children of Tokyo and Strange Weather in Tokyo